Auto Racing

Auto racing in North Carolina has grown from occasional competitions among speed-hungry moonshiners during the 1930s to a billion-dollar industry operating under the sponsorship of major corporations and attracting legions of devoted followers. As the availability of cars increased in the first decades of the twentieth century, organized races and auto rallies began to be held in northern and midwestern cities. In the rural South, where fewer people could afford cars, racing was slower to develop. An early advocate of the sport in North Carolina was automobile dealer Osmond Long Barringer Sr., who in 1924 built a one-mile pinewood track near Pineville (today part of the Charlotte metropolitan area).

Auto racing in North Carolina has grown from occasional competitions among speed-hungry moonshiners during the 1930s to a billion-dollar industry operating under the sponsorship of major corporations and attracting legions of devoted followers. As the availability of cars increased in the first decades of the twentieth century, organized races and auto rallies began to be held in northern and midwestern cities. In the rural South, where fewer people could afford cars, racing was slower to develop. An early advocate of the sport in North Carolina was automobile dealer Osmond Long Barringer Sr., who in 1924 built a one-mile pinewood track near Pineville (today part of the Charlotte metropolitan area).

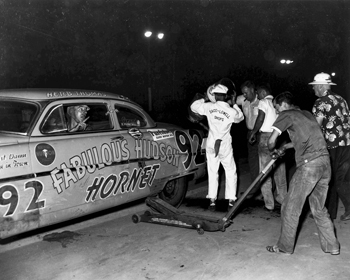

Many of North Carolina's original racing competitions matched law officers against local moonshiners who, with the fastest cars and the most innovative equipment, became formidable high-speed drivers capable of astounding-and often dangerous-maneuvers during their nightly liquor deliveries. Beginning in the mid-1930s, weekly races among moonshiners and others driving muscular cars were held at various rough-hewn tracks throughout the state. As these races grew in number and attendance increased, some ex-moonshiners became racing legends. Robert Glen "Junior" Johnson, born in Wilkes County in 1931, was the embodiment of the cunning, gritty southern renegade who drew the admiration of fans as auto racing began to develop into an organized spectator sport during the 1940s. Johnson learned the moonshine trade from his bootlegger father. He began competing in local races at age 15, and by his mid-twenties he had become a major talent on the growing racing circuit. Among Johnson's 50 career professional victories was the 1960 Daytona 500; he is also credited as the first driver to successfully use "drafting"-gaining additional speed by driving close behind another driver-to overcome faster cars during races.

The "down-home" appeal of auto racing was a key element in its growing popularity in North Carolina and other southern states during the latter half of the twentieth century. Although North Carolinians have participated in all types of motor sports, including drag racing and competing with "sprint" cars, "midget" cars, and karts, stock car racing-today featuring high-tech versions of commercial, assembly-line autos with V-8 engines and 700-plus horsepower-emerged as the most popular form of auto racing in the state. While heroes abounded in all sports, stock car drivers' personalities, regional allegiances, and other personal qualities became as important to many racing fans as the types of cars they drove or their success on the track. With its speed, noise, and danger, stock car racing came to be an affirmation of the most thrilling aspects of small-town southern life. These characteristics also contributed to its early reputation as a sport appealing predominately to rural white males.

Over the years, many North Carolina communities have had auto racing tracks-sometimes dirt, sometimes paved-where drivers and mechanics alike showcased their skills and built their reputations. The concentration of these local tracks, many of which have now closed or fallen into disrepair, was particularly high in the western Piedmont and Mountain region. But the local, rough-and-tumble nature of auto racing in the state began to shift decisively in 1947, when businessmen William France Sr. and Ed Otto formed the National Association for Stock Car Auto  Racing (NASCAR). NASCAR quickly established itself as the sanctioning body for races and race tracks; it also established tight control over the kinds of modifications that would be allowed in racing vehicles. The first official NASCAR event was held on 19 June 1949 at the three-quarter-mile dirt speedway in Charlotte. In NASCAR's first decade, much of the sport's attention was focused on glamorous races outside the state at "superspeedways" in Darlington, S.C., Talladega, Ala., and Daytona Beach, Fla. But in 1959, Charlotte businessman O. Bruton Smith and early driving star Curtis Turner joined to build Concord's 1.5-mile Charlotte Motor Speedway, and as the host of a 600-mile race that was longer than any other NASCAR event, the track helped return North Carolina to a central place in the sport.

Racing (NASCAR). NASCAR quickly established itself as the sanctioning body for races and race tracks; it also established tight control over the kinds of modifications that would be allowed in racing vehicles. The first official NASCAR event was held on 19 June 1949 at the three-quarter-mile dirt speedway in Charlotte. In NASCAR's first decade, much of the sport's attention was focused on glamorous races outside the state at "superspeedways" in Darlington, S.C., Talladega, Ala., and Daytona Beach, Fla. But in 1959, Charlotte businessman O. Bruton Smith and early driving star Curtis Turner joined to build Concord's 1.5-mile Charlotte Motor Speedway, and as the host of a 600-mile race that was longer than any other NASCAR event, the track helped return North Carolina to a central place in the sport.

For much of its history, NASCAR sanctioned three tracks in North Carolina: the Charlotte Motor Speedway, the one-mile oval North Carolina Speedway in Rockingham, and the half-mile "short track" North Wilkesboro Speedway. In 1972 NASCAR began a 33-year relationship with Winston-Salem's R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and its Winston cigarette brand, naming its top circuit the "Winston Cup." The Petty family of Level Cross came to be considered by many as the "first family" of stock car racing during this era, thanks to the exploits of Lee Petty, who won three NASCAR championships (1954, 1958, 1959), and his son Richard, who won 200 races during his career and earned the Winston Cup championship seven times (1964, 1967, 1971-72, 1974-75, and 1979). Kannapolis native Dale Earnhardt was one of the few drivers to rival Richard Petty's dominance, winning seven Winston Cup titles (1980, 1986-87, 1990-91, 1993-94) before his death in an accident during the final lap of the 2001 Daytona 500, the sport's premier race. Many of NASCAR's other champions and leading drivers have been born in North Carolina or call the state home today.

The 1990s were a decade of change and expansion for auto racing in North Carolina and across the nation. Although the stereotypical image of the racing fan as a blue-collar, white male remained intact, the sport's fan base grew in diversity, encompassing men from all economic and social backgrounds as well as an increasing number of women. Professionals at the highest levels of auto racing, however, have remained exclusively white males: by the early 2000s, no African Americans had successfully competed in NASCAR, and only two women were competing in NASCAR's Craftsman Truck Series.

Charlotte Motor Speedway nearly tripled its seating capacity to 167,000 in the early 1990s, and a lighting system for night racing was installed in 1992. The speedway became the first of its kind to offer lavish VIP suites and on-track condominiums. In 1995 Howard "Humpy" Wheeler, president and general manager of Charlotte Motor Speedway, and speedway owner Bruton Smith put the first publicly owned motor sports company, Speedway MotorSports, on the New York Stock Exchange. That company operates facilities in Charlotte and several other cities across the United States. In 1999 North Wilkesboro-based Lowe's Companies, Inc., secured the naming rights to the track, which is known today as Lowe's Motor Speedway. The 600-mile races run at Lowe's Motor Speedway remain the longest in the sport.

But the 1990s and the early 2000s also saw NASCAR shift away from its North Carolina roots. In 1996 the legendary short track at North Wilkesboro hosted its last Winston Cup race, as NASCAR moved that track's events to a speedway in New Hampshire, built as a part of an ongoing effort to diversify the sport's geographic base. And on 19 June 2003, the anniversary of North Carolina's first NASCAR event, the sport announced it would end its relationship with R. J. Reynolds in favor of a new partnership with wireless telecommunications provider Nextel Communications. Beginning in 2004 the sport's top circuit became known as the Nextel Cup. NASCAR officials cited the decision as a result of new limitations on the marketing of cigarettes, though many assume the decision was also tied to the larger effort to capture a more affluent national audience.

By the early 2000s, even as stock car racing expanded beyond its traditional southern base to tracks in many other regions of the country, it remained an annual billion-dollar industry in North Carolina, including brand product, television, restaurant, and hotel revenues, as well as money generated by the races themselves. Stock car racing has begun to receive media attention on a par with professional football, basketball, and baseball and is considered the nation's fastestgrowing sport.

References:

Jerry Bledsoe, The World's Number One, Flat-Out, All-Time Great Stock Car Racing Book (1995).

Pete Daniel, Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s (2000).

Peter Golenbock, American Zoom: Stock Car Racing (1993).

Randal L. Hall, "Before NASCAR: The Corporate and Civic Promotion of Automobile Racing in the American South, 1903-1927," Journal of Southern History 68 (August 2002).

Joe Menzer, The Wildest Ride: A History of NASCAR (2002).

Daniel S. Pierce, "The Most Southern Sport on Earth:NASCAR and the Unions," Southern Cultures 7, no. 2 (2001).

Sylvia Wilkinson, Dirt Tracks to Glory: The Early Days of Stock Car Racing as Told by the Participants (1983).

Additional Resources:

The NascarHall of Fame: http://www.nascarhall.com/

North Carolina Auto Racing Hall of Fame: http://www.ncarhof.com/

Hall, Randal L. “Carnival of Speed: The Auto Racing Business in the Emerging South, 1930-1950.” The North Carolina Historical Review 84, no. 3 (2007): 245–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523062.

1 January 2006 | Mazzocchi, Jay; Williams, Wiley J.