Colonization Societies

See also: Manumission Societies.

Colonization Societies were organized in the early nineteenth century to promote the relocation of African Americans, particularly free blacks, to places such as Haiti, Liberia, the American Midwest, and South America. After the American Revolution the number of freedmen and freedwomen had increased dramatically, due to the gradual emancipation in the North and extensive manumission between the Revolution and the early 1800s. Added to this population were the many slaves who had escaped during the confusion of war and thereafter passed for free.

Colonization Societies were organized in the early nineteenth century to promote the relocation of African Americans, particularly free blacks, to places such as Haiti, Liberia, the American Midwest, and South America. After the American Revolution the number of freedmen and freedwomen had increased dramatically, due to the gradual emancipation in the North and extensive manumission between the Revolution and the early 1800s. Added to this population were the many slaves who had escaped during the confusion of war and thereafter passed for free.

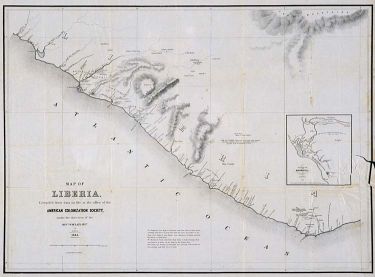

Colonization societies were numerous in North Carolina, especially in the Guilford-Randolph-Chatham County area heavily populated by Quakers. Although not remarkably antiracist, the Society of Friends opposed slavery; perhaps as a consequence, by 1827, 50 of the 106 antislavery societies in the slave states were concentrated in North Carolina. The American Colonization Society, which was formed in 1816 in Washington, D.C., and established Liberia in Africa, had "auxiliaries," or local chapters, throughout the South. The Raleigh Auxiliary Society for Colonizing the Free People of Colour of the United States was organized in 1819. By 1829 there were 11 auxiliaries of the American Colonization Society in North Carolina, located in communities as far west as Rowan County and as far east as Edenton and Murfreesboro. These early organizations were partly funded by the federal government under the 1819 Slave Trade Act.

Individuals in many areas of North Carolina emancipated their slaves, usually by provisions in their wills, and arranged for their transportation to Liberia. Free blacks and emancipated slaves from Craven, Pasquotank, Chowan, Bertie, Camden, Perquimans, Cabarrus, Iredell, Bladen, Hertford, Franklin, Edgecombe, Orange, Mecklenburg, Guilford, Forsyth, and Wake Counties were among the more than 1,200 who left the state under the auspices of the American Colonization Society. After the Civil War, the society focused on emigration, transporting more than 15,000 individuals from the United States to Africa by 1899. Well-known citizens such as Governor John Branch, Col. William Polk, Raleigh Register editor Joseph Gales Sr., Chief Justice John L. Taylor, and University of North Carolina president Joseph Caldwell lent their names to the cause.

Secular groups largely consisting of Quakers, the Meeting of Suffrages, and the North Carolina Manumission Society attempted to work with Colonization Society auxiliaries, composed of prominent non-Quaker North Carolinians (such as Governor James Iredell, who led the the Edenton Auxiliary) dedicated to gradual emancipation and removal of blacks, whom they viewed as a menace to white society. Quakers most committed to abolitionism, however, had long viewed colonization as a betrayal of their principles. As early as 1816, the New Garden (Guilford County) chapter had withdrawn from the Manumission Society because its members did not support the larger body's decision that colonization was an acceptable expression of the society's principles. An early sign of irreconcilable differences within the antislavery movement, this action of the New Garden Friends presaged the demise of the whole colonization enterprise by the 1830s. Supporters of manumission were divided between those who did not necessarily oppose slavery but desired the removal of free blacks and those who called for total emancipation. During the 1820s-a period of relative sectional peace between the Missouri Compromise and South Carolina's attempt to disallow a federal tariff unfavorable to the South-both of these positions managed to coexist.

Given the natural increase of the slave population, the removal of small numbers of free blacks availed little. This was true even in North Carolina, which contributed 10 percent of the 4,000 blacks who were colonized in Liberia between 1820 and 1837. Without substantial government funding, colonization was doomed to fail. Additionally, the more conservative sympathizers seemed to regard colonization as merely shoring up the institution of slavery by creating a society free of slave rebellion (free blacks were often wrongly suspected of encouraging slave revolts).

By 1830 the colonization movement had lost its momentum. Whites friendly to abolition often found themselves forced to move to the North, while those unwilling to embrace black freedom gave up the enterprise altogether. The emergence of a movement for immediate emancipation in the free states, the bloody Nat Turner Rebellion (1831), and other events and issues had destroyed the uneasy alliance among the various groups wrestling with the problem of slavery, and the colonization movement was effectively dead.

References:

Memory F. Mitchell, "Off to Africa-with Judicial Blessing," NCHR 53 (July 1976).

Mitchell and Thornton W. Mitchell, "The Philanthropic Bequests of John Rex of Raleigh," NCHR 49 (July 1972).

P. J. Staudenraus, The African Colonization Movement, 1816-1865 (1961).

Image Credit:

"Map of Liberia, 1845, published by the American Colonization Society (ACS). " Image courtesy of Kentucky Historical Society. Available from http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/Moments07RS/10_web_leg_moments.htm (accessed May 4, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Canipe, Jeremy T.; Mitchell, Memory F.