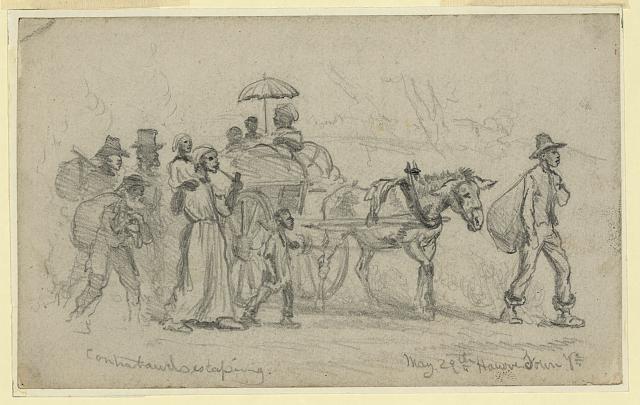

Contrabands

See also: Maroons.

Contrabands were slaves who escaped to Union lines during the Civil War. When the conflict began, the North's aim was primarily to preserve the Union, not to end slavery. Slaves who escaped to Union lines early in the war were often returned to their masters. However, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commanding Union forces at Fort Monroe, Va., refused to return three runaway slaves who reached his lines on 23 May 1861. Butler reasoned that since their former owner was in revolt against the United States, his slaves could be considered "contraband of war" and were not subject to return. Butler's opinion on this issue eventually became Union policy. According to the Confiscation Acts passed by the U.S. Congress during 1861 and 1862, all slaves used by the Confederate military for transportation or construction work would be freed if captured by Union forces. The term "contraband" remained in use throughout the war.

Contrabands were slaves who escaped to Union lines during the Civil War. When the conflict began, the North's aim was primarily to preserve the Union, not to end slavery. Slaves who escaped to Union lines early in the war were often returned to their masters. However, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commanding Union forces at Fort Monroe, Va., refused to return three runaway slaves who reached his lines on 23 May 1861. Butler reasoned that since their former owner was in revolt against the United States, his slaves could be considered "contraband of war" and were not subject to return. Butler's opinion on this issue eventually became Union policy. According to the Confiscation Acts passed by the U.S. Congress during 1861 and 1862, all slaves used by the Confederate military for transportation or construction work would be freed if captured by Union forces. The term "contraband" remained in use throughout the war.

In North Carolina, the Union-held enclaves around Plymouth, Washington, Beaufort, Morehead City, Roanoke Island, and especially New Bern attracted large populations of contrabands. Some made their way to the Union towns singly or in small groups; larger numbers returned with Union raiding parties. Many of these black refugees found employment with the Federals as laborers, teamsters, servants, laundresses, or skilled craftsmen, as well as serving as scouts, spies, soldiers, or sailors. Many of the more than 5,000 black North Carolinians who joined the Union army or navy had been contrabands.

Faced with a huge influx of contrabands, the Union commander in North Carolina during early 1862, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, appointed Vincent Colyer, a New York abolitionist, artist, and former official of the YMCA, to be superintendent of the poor. Beginning on Roanoke Island, where by late spring there were about 1,000 contrabands, Colyer offered the able-bodied men among them jobs as laborers at $8.00 a month plus clothing.

By late spring 1863, recruitment of black soldiers from the contraband population in eastern North Carolina was well under way. Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts and army officers from that state stationed in New Bern were instrumental in raising such regiments in North Carolina. At this time black recruits from the state were organized into three regiments of infantry and one regiment of artillery. On a few occasions, when Union-occupied towns were under threat of Confederate attack, contraband laborers were issued weapons and ordered into auxiliary military companies. In January 1864 approximately 600 contrabands were placed under arms in New Bern. By the end of the war, the contraband population around New Bern was estimated as high as 15,000. A small number of contrabands lived on Hatteras Island, and more than 3,000 were located in and around Union-occupied Beaufort and Morehead City. Many of them made a living on the water fishing, oystering, or carrying freight and passengers around the area.

Roanoke Island was another important center of contraband life during the war. By the beginning of 1865, it was estimated that more than 3,000 blacks occupied nearly 600 houses on the island; these contrabands spent their time farming, fishing, splitting shingles, or working as federal government laborers. Many healthy men of military age served in the Union army, so the colony had a high percentage of children, women, and older men. At the war's end, the contrabands on Roanoke disbanded, as much of the land was returned to secessionist owners who had been pardoned by the Union.

References:

Patricia C. Click, Time Full of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, 1862-1867 (2001).

Vincent Colyer, A Report of the Services Rendered by the Freed People to the United States Army, in North Carolina, in the Spring of 1862, after the Battle of Newbern (1864).

Joe A. Mobley, James City: A Black Community in North Carolina, 1863-1900 (1980).

David Stick, The Outer Banks of North Carolina, 1584-1958 (1958).

Image Credit:

"Contrabands escaping." Created by Forbes, Edwin, May 29, 1864. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Available from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004661467/ (accessed May 21, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Norris, David A.