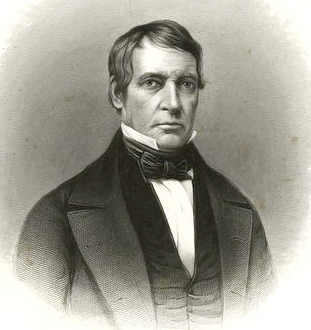

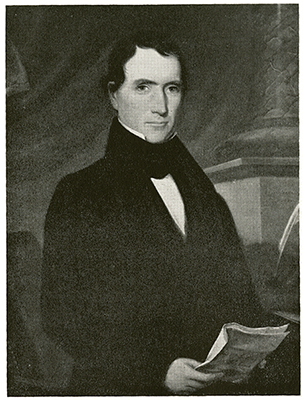

King, William Rufus Devane

7 Apr. 1786–18 Apr. 1853

William Rufus Devane King, congressman, diplomat, U.S. senator, and vice-president of the United States, was born in Sampson County, the second son of William and Margaret Devane King. His father was a Revolutionary patriot, planter, justice of the peace, delegate to the North Carolina ratification convention in 1789, and member of the North Carolina House of Commons. His mother was a descendant of a prominent Huguenot family.

William Rufus Devane King, congressman, diplomat, U.S. senator, and vice-president of the United States, was born in Sampson County, the second son of William and Margaret Devane King. His father was a Revolutionary patriot, planter, justice of the peace, delegate to the North Carolina ratification convention in 1789, and member of the North Carolina House of Commons. His mother was a descendant of a prominent Huguenot family.

Brought up in relative affluence, King attended Grove Academy near Kenansville, Fayetteville Academy, and the Preparatory School at The University of North Carolina. He was a student at the university from 1801 until 1804, when he left at the end of his junior year to study law under William Duffy at Fayetteville. In late 1805 he obtained a license to practice and set up an office in Clinton.

King sought a seat in the North Carolina House of Commons in 1808 and was elected as a Republican. In the ensuing session, he defended resolutions to support measures taken by the Jefferson administration against the aggressive actions of France and Great Britain. A productive member of the house, he was reelected in 1809 but resigned before the end of the session to become solicitor of the First Circuit of the state court.

In 1810, he was elected to represent the Wilmington District in the United States Congress. Only twenty-five when the Twelfth Congress met in November 1811, King joined an able group of young men with whom he was destined to be associated for most of his life, including John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay. A member of the youthful War Hawk faction, King supported measures to strengthen the military power of the United States and generally approved the conduct of the War of 1812. Though neither an ardent expansionist nor a staunch defender of the carrying trade, he maintained that American rights should be asserted.

Reelected without opposition in 1813 and 1815, King joined other young political figures in supporting early phases of the nationalistic program proposed by President James Madison after the War of 1812. Before his full influence on the program could be exerted, however, he resigned his seat in the House of Representatives in April 1816 to become secretary of the legation to the Court of Naples and the Two Sicilies and to the Court of Russia. His objective was to acquire knowledge about Europe through travel and observation. Joining William Pinkney, who had been named minister to the two courts, King went first to Naples and later to Russia. In the summer of 1817, he resigned his post and returned to the United States.

In 1818 King moved to Alabama to take advantage of the unprecedented economic opportunity there and to enhance his political career. He acquired large land-holdings in Dallas County and played a major part in the founding of Selma. Elected to represent Dallas County in the Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1819, he was appointed to the Committee of Fifteen established to draw up a proposed draft of the constitution. In convention debates, King supported a more conservative constitution as opposed to one characterized by "extreme" democracy.

In 1819, he was elected by the new state legislature to represent southern Alabama in the U.S. Senate. On Capitol Hill he supported the Missouri Compromise and became a leader in the fight for generous land legislation and an opponent of protective tariffs. He exerted a powerful influence in support of the Land Act of 1820 and relinquishment laws for the benefit of western farmers who had overbought government land.

King was reelected to the Senate in 1822 by a narrow margin and in 1828 without opposition. Although he supported John Quincy Adams for president in 1824, he soon became disillusioned with his policies and joined many other Alabamians in endorsing Andrew Jackson. He opposed the tariff acts of 1824 and 1828 and took a special interest in Indian removal and in public land measures. After Jackson's election, King became one of the major administration leaders in the Senate.

While King was chairman of the Public Lands Committee during the Twenty-second Congress, the committee issued a report opposing a distribution scheme favored by a group led by Henry Clay and advocating instead a reduction in the price of public land. The report constituted a source document for later advocates of cheap public land and opponents of the distribution of government revenues. Throughout his tenure in the Senate, King continued to support land policies that were beneficial to settlers and to oppose distribution. In 1832, he opposed the bill proposing recharter of the Bank of the United States because it had been presented for partisan reasons and because no modifications had been proposed to correct abuses. Subsequently, he vigorously opposed the bank's efforts to force reconsideration of the bank measure.

As a delegate to the Democratic convention in Baltimore in 1832, King was appointed to the Committee on Rules and reported for the committee a rule requiring a two-thirds vote for the selection of a nominee, a rule continued by the Democratic party until 1936. Although he opposed the nomination of Martin Van Buren for the vice-presidency, the Alabama senator supported the party ticket.

Despite severe criticism by the advocates of nullification because of his stand at the time of the crisis, King was reelected to the Senate in 1834 with only slight opposition. While maintaining his reservations about Martin Van Buren, he supported him for the presidency in 1836. Deeply concerned about the panic of 1837 because it brought personal suffering and threatened to split the Democratic party, he supported repeal of the Distribution Act and creation of the Independent Treasury System as a means to help alleviate existing problems.

When trouble arose in the 1830s over the distribution of Abolitionist literature in the South and the reception of Abolitionist petitions by the Senate, King took a moderate position. He supported the view that the distribution of literature should be limited at the source and that petitions should be received by the Senate and rejected.

At the close of the Twenty-fourth Congress, he was elected president pro tempore of the Senate and served until 1841. Previously, he had presided over the Senate many times and was regarded as the foremost expounder of Senate rules.

As early as 1838, King began to think of securing the Democratic vice-presidential nomination in 1840. But despite strong support for him in Alabama and Pennsylvania, the Democratic National Convention failed to agree on a single vice-presidential candidate. Rather than divide the party, King withdrew in favor of Richard M. Johnson. Late in 1840, he was reelected to the Senate for a fifth term but with strong opposition from his Whig opponent, John Gayle.

After 1841, King was one of the leaders of the opposition in the Whig-controlled Senate. As such, he opposed attempts to repeal the Independent Treasury Act, to revive the Second Bank of the United States in new forms, to provide for distribution of governmental revenues to the states, to impose a higher tariff, and to restrict the Senate's right to full debate on all issues. Though only partially successful in his resistance to the Whig program on banking and manufacturing, King won the fight to protect the Senate's right to full debate. In taking such positions, he was thrown in support of John Tyler, the states' rights Whig who succeeded to the presidency after the death of William Henry Harrison. He also supported Tyler in his quest for the annexation of Texas.

As the election of 1844 neared, strong support again developed for King for the vice-presidency. However, when Van Buren lost the presidential nomination to James Knox Polk, a southerner, his hopes were shattered.

In April 1844 King resigned from the Senate to become minister to France, serving until September 1846. In that position, he contributed greatly to the success of three measures important to the United States: the annexation of Texas, the settlement of the Oregon boundary, and the Mexican War. King convinced the French government that it would be unwise to join England in its proposed plan of intervention in Texas, thus permitting the United States to annex Texas without fear of foreign interference. He also obtained assurances that France would not intervene against the United States in England's behalf during the Oregon controversy and that it would not act in a manner unfriendly to the United States during the Mexican War.

Returning to Alabama in November 1836, King declined to become a candidate for governor in 1847 and instead began a campaign to unseat Dixon Hall Lewis, who had been elected to his old seat in the Senate. Opposed by both the Whigs and the Lewis element of the Democratic party in the 1847 contest, however, he was unable to secure a majority in the legislature and suffered his only defeat at the state level. Shortly afterwards, he was nominated for the vice-presidency by the Alabama Democratic party but received only scattered support at the National Convention. When Arthur P. Bagby resigned from the Senate in June 1848, King was appointed to replace him; he was elected to the seat in 1849 after making concessions to the states' rights wing of the Democratic party.

Returning to Alabama in November 1836, King declined to become a candidate for governor in 1847 and instead began a campaign to unseat Dixon Hall Lewis, who had been elected to his old seat in the Senate. Opposed by both the Whigs and the Lewis element of the Democratic party in the 1847 contest, however, he was unable to secure a majority in the legislature and suffered his only defeat at the state level. Shortly afterwards, he was nominated for the vice-presidency by the Alabama Democratic party but received only scattered support at the National Convention. When Arthur P. Bagby resigned from the Senate in June 1848, King was appointed to replace him; he was elected to the seat in 1849 after making concessions to the states' rights wing of the Democratic party.

King performed his last great service as senator during the crisis of 1850. One of the leading advocates of compromise in the Senate, he took a moderate position himself and called on both northerners and southerners to make concessions in order to save the Union. Chosen presiding officer of the Senate after the death of President Zachary Taylor, King sought to influence his colleagues to take a less emotional approach to the problems before them. As chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations, he was instrumental in securing adoption of the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty.

Although responsible for ensuring passage of the compromise measures of 1850, King deserves even more credit for bringing about the acceptance of these measures by the South. Conceding that southerners had just cause to complain about this legislation, he nevertheless advised acquiescence and spoke against taking steps that might threaten the Union. He also took a lead in reorganizing the Democratic party in Alabama and in settling North-South differences within the national party.

Partly in recognition of his distinguished record and partly to conciliate the supporters of James Buchanan, King was chosen as the vice-presidential nominee of his party in 1852. But by the time of his landslide victory, he was extremely ill with tuberculosis. In December 1852 he resigned from the Senate and went to Cuba to recover his health. By authorization of a special act of Congress, he was sworn in as vice-president in Cuba on 24 Mar. 1853. He returned to the United States in April and died the same month.

Although King attracted less attention and received less recognition than some of his more colorful contemporaries, he made significant contributions to his state and country. Probably no other elected representative in American history has equaled his ability as presiding officer of the Senate. Acknowledged as the outstanding authority on Senate rules, he was elected president pro tempore on many occasions; moreover, other presiding officers often called on him to preside during their absence. From the floor, King was vigilant to see that presiding officers followed established rules and that decorum was maintained. His moderation and firmness contributed to the reduction of sectional antagonism growing out of the slavery question. Throughout his political career, he maintained an allegiance to the party of Jefferson. He was a staunch supporter of states' rights and a strong opponent of a broad construction of the Constitution.

King, who never married, was a member of the Episcopal church. In appearance, he was tall and slender. He was praised for his courtly manners, courtesy, hospitality, and scrupulous attention to monetary obligations. Portraits of him appear in the State Archives Building in Montgomery, Ala., and at The University of North Carolina. After his death at his home in Dallas County, his body was interred in a vault on the plantation but was later moved to the City Cemetery in Selma.

References:

Samuel F. Bemis, ed., The American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy, vol. 5 (1927–29).

Biog. Dir. Am. Cong. (1928).

Lewy Dorman, Party Politics in Alabama from 1850 through 1860 (1935).

Walter Jackson, Alabama's First United States Vice President, William Rufus King (1952).

John M. Martin, "William R. King and the Compromise of 1850," North Carolina Historical Review (Autumn 1962), "William R. King: Jacksonian Senator," Alabama Review (October 1965), and "William R. King and the Vice Presidency," Alabama Review (January 1963).

Obituary Addresses on the Occasion of the Death of the Hon. William R. King (1854).

Albert J. Pickett, History of Alabama (1851).

Additional Resources:

"King, William Rufus de Vane, (1786 - 1853)." Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Washington, D.C.: The Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=K000217 (accessed September 11, 2013).

"William Rufus King." Encyclopedia of Alabama. http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1886 (accessed September 11, 2013).

Brooks, Daniel F. "Who is William Rufus King?" Alabama Department of Archives and History. http://www.alabamamoments.state.al.us/sec09.html (accessed September 11, 2013).

"William Rufus King, 13th Vice President (1853)." Senate Historical Office. UNited States Senate. http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_William_R_King.htm (accessed September 11, 2013).

Image Credits:

Buttre, John Chester, engraver. "William Rufus King, Vice President of the United States." 1852. Emmet Collection of Manuscripts Etc. Relating to American History. New York Public Library Digital Gallery. http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?421083 (accessed September 11, 2013).

"Hon. W.R. King of Alabama." c1852 June 18. Popular Graphic Arts. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003681719/ (accessed September 11, 2013).

Cooke, George, 1838. "William Rufus King." North Carolina Portrait Index, 1700-1860. Chapel Hill: UNC Press. p. 133. (Digital page 147). https://www.worldcat.org/title/832326?oclcNum=832326. Accessed 10/15/2014.

1 January 1988 | Martin, John M.