Printing

In 1749 North Carolina's provincial government brought James Davis from Virginia to become the colony's public printer and establish the first printing press in the then-capital city of New Bern. Prior to Davis's arrival, printing jobs had been sent to Williamsburg, Va., or Charleston, S.C. While North Carolina was the ninth of the 13 colonies to establish a printing operation, it did so 110 years after the colonies' first press appeared in Massachusetts. A number of factors contributed to North Carolina's relatively late entrance into the world of type. The lack of a press had helped the provincial government control the distribution of information. As late as 1671, Lord Proprietor Sir William Berkeley expressed his relief that North Carolina had "no free schools and no printing, and I hope we shall have none these hundred years." Also, many of the American colonies' earliest presses had started in large urban centers such as Boston (1639), Philadelphia (1685), and New York (1693). North Carolina, a primarily agricultural province, did not have the population density of large cities to help support a printer. The province's closest neighbors, Virginia and South Carolina, only established presses a decade before North Carolina.

In 1749 North Carolina's provincial government brought James Davis from Virginia to become the colony's public printer and establish the first printing press in the then-capital city of New Bern. Prior to Davis's arrival, printing jobs had been sent to Williamsburg, Va., or Charleston, S.C. While North Carolina was the ninth of the 13 colonies to establish a printing operation, it did so 110 years after the colonies' first press appeared in Massachusetts. A number of factors contributed to North Carolina's relatively late entrance into the world of type. The lack of a press had helped the provincial government control the distribution of information. As late as 1671, Lord Proprietor Sir William Berkeley expressed his relief that North Carolina had "no free schools and no printing, and I hope we shall have none these hundred years." Also, many of the American colonies' earliest presses had started in large urban centers such as Boston (1639), Philadelphia (1685), and New York (1693). North Carolina, a primarily agricultural province, did not have the population density of large cities to help support a printer. The province's closest neighbors, Virginia and South Carolina, only established presses a decade before North Carolina.

The N.C. Assembly brought Davis to New Bern to help with the distribution of their proceedings and laws. Prior to his establishment as the public printer, multiple copies of such documents were made by hand for key officials. Davis's first New Bern publication was the Journal of the House of Burgesses of the Province of North Carolina, printed in 1749. He also issued the first collection of public laws printed in North Carolina as authorized by the Assembly of 1747, titled A Collection of All the Public Acts of Assembly, of the Province of North Carolina: now in Force and Use, etc. (1751). Davis published later editions of the acts of the Assembly and also started North Carolina's first newspaper, the North-Carolina Gazette, in New Bern in 1751. He remained active as a printer until his death in 1785.

Other printers made significant contributions to the early history of North Carolina. Andrew Steuart, a native of Ireland, established the second printing operation in North Carolina in Wilmington near the end of 1763 (or possibly in early 1764). Steuart supported himself by establishing the colony's second newspaper, also called the North-Carolina Gazette. Adam Boyd, a native of Pennsylvania, purchased Steuart's press and type after Steuart's death in 1769 and established himself as a printer in Wilmington. That year he started the Cape-Fear Mercury, which proved to be successful. Abraham Hodge, a native of New York, worked as a printer for Samuel Loudon during the American Revolution. Around 1785, Hodge moved to Halifax to establish a printing office. He was appointed North Carolina state printer in 1785, after Davis's death. Hodge worked in partnership with a number of different printers and established printing offices in Edenton, Fayetteville, and New Bern in addition to Halifax. He served as public printer for 15 years, started three newspapers, and printed almanacs. His career helped establish a broader publication base within North Carolina. Other early luminaries in the North Carolina printing industry include Joseph Gales, François-Xavier Martin, and John Christian Blum.

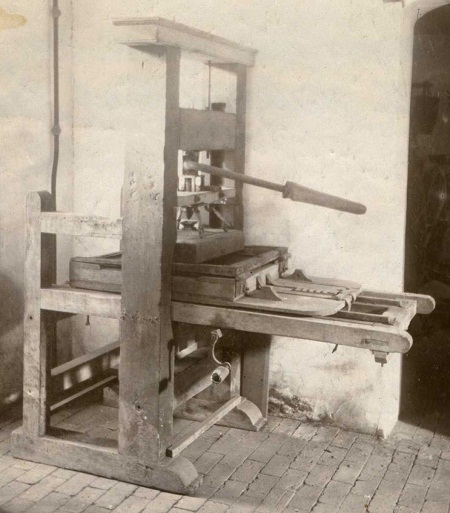

From Johann Gutenberg's printed Bible to colonial newspapers, the art of printing had made little progress. Impressions were made from the inked type onto paper by a slow process dating back several centuries. Ink was made of linseed oil and lampblack. The process of hand-setting the type letter by letter was tedious and limited printers in styles and sizes. In 1820, however, the all-metal "Washington" press came on the market. It was still operated by hand but was much faster than the ancient "screw-style" press. North Carolina's larger cities got the first of these presses for newspaper and circular printing.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century printers were still composing type by hand. This changed in 1890 with the invention of the Mergenthaler Linotype. This metal casting machine produced type in a solid lead casting, one line at a time. When the type was no longer needed the line of type was remelted to form new lines. A milestone development for North Carolina printers, although not as obvious as the new presses or Linotype, was the publication of the Franklin Price Book, a cost-setting reference guide that assured a profit from each printing job. Developed in the 1920s, this book remains a vital tool for public printers.

The technology of printing once again changed dramatically as new offset printing presses and related electronic typesetting came on the market in the early 1950s. Soon afterward, the introduction of computers revolutionized the printing industry. Even a one-person print shop could produce very professional work through computer imagery and specialized programs. North Carolina printing companies grew to serve the needs of a variety of customers, with firms such as Edwards & Broughton and Seeman among the leaders. One of the largest commercial printing firms in the nation, Meredith-Burda, established a large plant in Newton in the 1960s. This firm prints Better Homes & Gardens magazine and many advertising tabloids with press runs in the millions of copies.

References:

Robert F. Karolevitz, From Quill to Computer: The Story of America's Community Newspapers (1985).

Douglas C. McMurtrie, Eighteenth-Century North Carolina Imprints, 1749-1800 (1938).

George Washington Paschal, A History of Printing in North Carolina (1946).

Mary L. Thornton, Official Publications of the Colony and State of North Carolina, 1749-1939: A Bibliography (1954).

Additional Resources:

"FIRST PRINTING PRESS IN N.C." North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?ct=ddl&sp=search&k=Markers&sv=C-3.

Reavis, Scott Aaron. "James Davis: North Carolina's First Printer." Master's paper, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, July, 2000. http://ils.unc.edu/MSpapers/2628.pdf.

Weeks, Stephen B. The Press of North Carolina in the Eighteenth Century. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Historical Printing Club. 1891.

Thornton, Mary L. “Public Printing in North Carolina, 1749-1815,” North Carolina Historical Review. July 1944: 181-202.

Elliot Jr., Robert N. “James Davis and the Beginning of the Newspaper in North Carolina,” North Carolina Historical Review. Winter 1965: 1-20.

Image Credits:

"Photograph, Accession#: H.1946.14.82." Circa 1900-1920. From the North Carolina Museum of History.

1 January 2006 | Middlesworth, Chester Paul; Pyatt, Timothy D.