Sherman's March

During the Civil War, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's March to the Sea culminated in the Union's capture of Savannah, Ga., in December 1864. Instead of transferring his veteran army by water to Virginia, where Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had Gen. Robert E. Lee bottled up around Richmond, Sherman received permission to invade the Carolinas. He particularly wanted to apply the fullest measure of "total war" to South Carolina as punishment for bringing on the war. He planned to move directly on Columbia, S.C., and from there to Fayetteville on the Cape Fear River in North Carolina. Then the Union army would push eastward to Goldsboro, which was connected to the coast by two railroads. Along this route Sherman could cut communication lines, destroy public and industrial property, and dampen morale. By applying total war to the home front, Sherman expected to instill a defeatist psychology in southern civilians and soldiers alike. His ultimate objective was to combine with Grant's forces at Richmond and crush Lee's army, thus ending the war.

During the Civil War, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's March to the Sea culminated in the Union's capture of Savannah, Ga., in December 1864. Instead of transferring his veteran army by water to Virginia, where Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had Gen. Robert E. Lee bottled up around Richmond, Sherman received permission to invade the Carolinas. He particularly wanted to apply the fullest measure of "total war" to South Carolina as punishment for bringing on the war. He planned to move directly on Columbia, S.C., and from there to Fayetteville on the Cape Fear River in North Carolina. Then the Union army would push eastward to Goldsboro, which was connected to the coast by two railroads. Along this route Sherman could cut communication lines, destroy public and industrial property, and dampen morale. By applying total war to the home front, Sherman expected to instill a defeatist psychology in southern civilians and soldiers alike. His ultimate objective was to combine with Grant's forces at Richmond and crush Lee's army, thus ending the war.

During the Carolinas campaign, Sherman's army of 60,000 troops and 2,500 wagons was divided into two wings, sometimes forming a front over 40 miles wide. While Sherman's forces were marching through South Carolina, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston became the new commander of Confederate forces in the Carolinas. Sherman correctly surmised that Johnston would attempt to unite his widely scattered army and fight at a place and time of his own choosing. As early as mid-January 1865, at least one North Carolina newspaper began preparing its readers for invasion. A month later, when Fort Fisher and Wilmington on the coast fell to the Union, a wave of despondency hit the state. Many people, fearing that they might be in Sherman's direct path, hid their valuables in an effort to save them.

Because Sherman had cut himself off from his supply base at Savannah, his men were reduced to foraging extensively from the countryside as they moved through the Carolinas in early 1865. Strict regulations limited foraging parties, but there was a wide discrepancy between these orders and the actions of some of the troops, who operated more as mounted robbers than as disciplined foragers. Much of the wanton destruction of property in the two Carolinas was the work of this self-constituted group, known primarily as "bummers." Unsupervised by officers, these men operated on their own.

The origin of the term "bummer" is obscure; however, by the time of Sherman's March to the Sea in the fall of 1864, it had come into general usage. A member of the general's staff defined a bummer as a "raider on his own account, a man who temporarily deserts a place in the ranks and starts up an independent foraging mission." But most soldiers in Sherman's army designated all foragers "bummers" whether authorized or unauthorized.

By 8 Mar. 1865 Sherman's entire army was on North Carolina soil in the vicinity of Laurel Hill Presbyterian Church (now Scotland County), facing a formidable march. Early on the morning of 10 March at Monroe's Crossroads west of Fayetteville, a part of the cavalry under Brevet Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick was surprised and temporarily driven from the field by Confederate horsemen led by Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton. But the Union force regained control of its camp and thus opened the way for the Federal occupation of Fayetteville the next day.

The town and surrounding countryside suffered much at the hands of Sherman's men, who pillaged and destroyed property, including the arsenal. While at Fayetteville, Sherman took the opportunity to rid his columns of the 30,000 black and white refugees who had been following his army. He considered them "useless mouths."

Leaving Fayetteville, Sherman crossed the Cape Fear and turned east toward Goldsboro. On 16 March a small Confederate force fought a delaying action against Sherman's left wing at Averasboro, and three days later Johnston's entire army of 21,000 troops attacked the left wing at Bentonville about 20 miles west of Goldsboro. The first day's fight was by far the bloodiest, ending in a draw. But the Union went on to win the three-day battle-the largest ever fought on North Carolina soil.

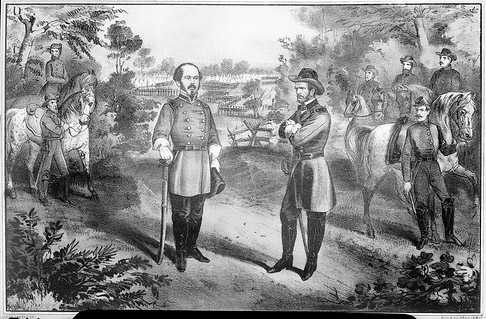

After his victory at Bentonville, Sherman allowed Johnston to withdraw to Smithfield. The Union general moved on to Goldsboro, where, on 23 March, he linked up with additional troops under Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield. After receiving news of the fall of Richmond, Sherman turned toward Raleigh, with Johnston retreating before him. On the evening of 12 April, peace commissions from Raleigh arrived at Sherman's headquarters at Clayton. By this time Gen. Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox, Confederate troops were evacuating the capital of North Carolina, and Johnston was seeking permission from President Jefferson Davis to contact Sherman about ending hostilities. The generals met on three occasions at the James Bennett home west of Durham. The surrender terms drafted at the first two meetings, on 17 and 18 Apr. 1865, were too generous for authorities in Washington, D.C.; at the third meeting, on 26 April, Sherman and Johnston drafted a more satisfactory agreement. The terms were similar to those Lee received from Grant at Appomattox. Except for the stacking of arms at Greensboro and a few minor skirmishes between Union and Confederate troops, the war in North Carolina was over.

References:

John G. Barrett, Sherman's March through the Carolinas (1956).

Mark L. Bradley, Last Stand in the Carolinas: The Battle of Bentonville (1996).

Bradley, This Astounding Close: The Road to Bennett Place (2000).

Jacqueline Glass Campbell, When Sherman Marched North from the Sea: Resistance on the Confederate Home Front (2003).

Lloyd Lewis, Sherman: Fighting Prophet (1932).

William Tecumseh Sherman, Memoirs, vol. 2 (1875).

Image Credit:

"Gen Johnston's Surrender- a Painting." General Joseph E. Johnston surrenders to Union General William T. Sherman at Bennett Place, April 1865. From the Barden Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC. Call #: N_53_15_1953. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/4290717242/ (accessed May 15, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Barrett, John G.