Cottonmouth

Agkistrodon piscivorus

by Therese Conant

Updated by Andrew M. Durso and Jeff Hall

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Classification

Class: Reptilia (reptiles)

Order: Squamata (snakes & lizards)

Suborder: Serpentes (snakes)

Family: Viperidae (vipers)

Average Size

Adults measure 3ft.–4 ft. but are known to reach 6 ft. The record is 74 in.

Food

Cottonmouths have a very generalized diet; they eat fish, other snakes, small mammals, birds, lizards, amphibians, turtles, crayfish and insects. Cottonmouths exhibit an ontogenetic shift in foraging strategy, with juveniles ambushing mostly amphibian prey from open sites around the edges of wetlands, while adults employ more active foraging in a variety of habitats.

Breeding

Like most pit vipers, cottonmouths are viviparous (give birth to living young). Both males and females reach sexual maturity at 2–3 years. Mating takes place in both spring and fall. Females give birth to a litter of 3–14 young between August and October. Females may congregate before giving birth and remain with their broods, possibly to defend them, for several days. Because breeding is energetically expensive, many vipers, including cottonmouths, commonly reproduce in alternating years.

Young

Neonates (newborns) are approximately 9.5 in.–10 in. long and are strongly patterned with light-centered dark brown to reddishbrown crossbands. The tip of the tail is yellow and is used as a lure to attract prey.

Life Expectancy

10–20 years or more.

Range and Distribution

Cottonmouths range from southeastern Virginia through eastern North and South Carolina, south to Florida, west to Texas, and north along the Mississippi River to southern Illinois and Indiana. The Eastern cottonmouth is restricted to Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida and Alabama. In North Carolina, cottonmouths are predominantly found in the Coastal Plain and on some parts of the Outer Banks. In a few places, they are the most abundant snake species. Pre-1900 records also exist from the lower Piedmont, but the Wake County sightings reported each year are superficially similar nonvenomous watersnakes (Nerodia).

General Information

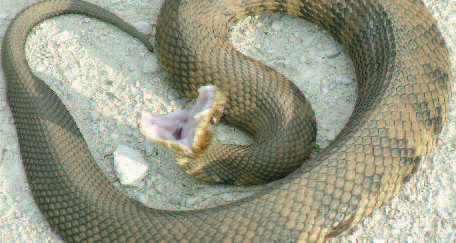

Also known as the water moccasin, the cottonmouth derives its common name from the white color of the inside of its mouth, which is revealed when the snake gapes to defend itself. Two species of the genus Agkistrodon occur in the United States, the cottonmouth and the copperhead (A. contortrix). Both occur in North Carolina. There are three subspecies of cottonmouth. The subspecies in North Carolina is the Eastern cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus piscivorus) Along with copperheads and rattlesnakes, the cottonmouth is a member of the viper family (Viperidae). Its venom toxicity ranks fourth of the six species of North Carolina venomous snakes (after the coral snake, eastern diamondback rattlesnake, and timber rattlesnake).

Description

The venomous cottonmouth, like all pit vipers, has a facial pit for sensing infrared radiation (heat), but unlike rattlesnakes, it lacks a rattle. The head is distinctly wider than the neck, with a dark bar on both sides from the eye to the angle of the jaw. There are nine large scales on the crown of the head, and the pupils of the eyes are vertically elliptical. The cottonmouth is patterned with dark crossbands invaded by light olive or brown centers. These dark crossbands are widest on the sides of the animal and narrowest on the top. This is the opposite of most nonvenomous water snakes that may resemble cottonmouths superficially (in water snakes, the dark crossbands have the widest part of the band on the top). Juveniles have bright yellow or greenish tail tips, and the details of the crossband pattern are most evident in this age group. Older individuals are often completely dark and unpatterned.

History and Status

The cottonmouth is common in eastern North Carolina. The cottonmouth is not on federal or state species protection lists. However, as development increases in eastern North Carolina, loss of habitat could affect cottonmouth populations.

Habitat and Habits

The cottonmouth is the most aquatic of North American venomous snakes and can be found in most habitats associated with water. Like other ectothermic (“cold-blooded”) reptiles, cottonmouths bask on branches, logs or stones at the water’s edge. They are most active at night and become inactive at the onset of cold weather, brumating underground over winter. Common hibernacula are on rocky wooded hillsides, in crayfish burrows, under rotting stumps and in mammal burrows. If approached, some cottonmouths will retreat but others are defensive and will stand their ground. They often coil, vibrate their tail and open their mouth to reveal the white inner lining.

Human Interactions

The Eastern cottonmouth is venomous and should not be approached. Human mortality due to a cottonmouth bite is unreported for North Carolina, but has been recorded elsewhere. However, experiments with wild cottonmouths showed that, when confronted, over 50 percent of cottonmouths tried to escape, and 78 percent used threat displays as a secondary defense; only 36 percent ultimately bit an artificial hand used in the tests. Some venomous snakes can control the amount of venom and may elect to bite defensively without injecting venom (a “dry bite”); since venom is expensive to produce and is primarily used to kill prey, a prudent snake should not want to waste venom on a predator, which it cannot then eat.

NCWRC Interaction

Cottonmouths are relatively common occupants of North Carolina’s wetlands, and are often observed basking during the day and foraging at night by human visitors to these ecosystems. Long-term monitoring can alert biologists to potential declines, especially those associated with wetland drainage and degradation due to development of the surrounding upland. Monitoring of wetland snake populations is usually accomplished by setting minnow traps to capture snakes. Because small cottonmouths are ambush predators rather than active foragers, they rarely enter minnow traps, and so their abundance may be underestimated if visual surveys are not used. Actively-foraging adult cottonmouths are often too large to fit into trap entrances, which are usually about 1.5 inches in diameter, although occasionally one will try to squeeze its way in to consume a trapped water snake.

References:

Beane, J. C., A. L. Braswell, J. C. Mitchell, and W. M. Palmer. 2010. Amphibians & Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia. 2nd edition. University of North Carolina Press.

Ernst, C. H. and E. M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Books.

Eskew, E., J. Willson, and C. Winne. 2009. Ambush site selection and ontogenetic shifts in foraging strategy in a semi aquatic pit viper, the Eastern cottonmouth. Journal of Zoology 277:179-186.

Gibbons, J. W. and M. E. Dorcas. 2002. Defensive Behavior of Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) toward Humans. Copeia 2002:195-198.

Gibbons, J. W. and M. E. Dorcas. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press.

Palmer, W. M. and A. L. Braswell. 1995. Reptiles of North Carolina. University of North Carolina Press.

Credits:

Photos by Gene Ott Photography, Karlton D. Rebenstouf, US Coast Guard, Dave Badger and Steve Maslowski.

Produced 2011 by the Division of Conservation Education; Cay Cross–Editor.

1 January 2011 | Conant, Therese; Durso, Andrew M.; Hall, Jeff