WWI: Combat on the Western Front

When Congress declared war against Germany in the spring of 1917, the United States military was poorly prepared to train and arm volunteers and draftees. The regular army was small and did not have enough places to train the large number of Americans needed to fight in France. Although most United States soldiers received at least six months of training, some troops were shipped to France with only one week of military experience. Despite an all-out effort, it was 1918 before enough American soldiers arrived overseas to end the war.

When Congress declared war against Germany in the spring of 1917, the United States military was poorly prepared to train and arm volunteers and draftees. The regular army was small and did not have enough places to train the large number of Americans needed to fight in France. Although most United States soldiers received at least six months of training, some troops were shipped to France with only one week of military experience. Despite an all-out effort, it was 1918 before enough American soldiers arrived overseas to end the war.

The trench warfare of World War I was much like what North Carolina Confederates had experienced at Petersburg, Virginia, near the end of the Civil War (1861–1865). But technology of the early 1900s had greatly changed the weapons soldiers used. Without enough weapons of their own, United States troops often trained and fought using French and British rifles, machine guns, and artillery. British and French instructors taught American troops to use the bayonet, trench knife, and hand grenade in close combat. Doughboys also learned how to dig and repair trenches, how to listen for incoming artillery shells, how to protect themselves from poison gas, and how to string and cut through barbed wire.

Conditions at the front were almost always wretched. Roy Jackson Marshall of Forsyth County noted his first reaction to life in the trenches in an April 1918 diary entry:

My first 24 hours on the Western Front. Arrived about 11 o’clock p.m. muddy and tired. It was raining and had been so for many days. Mud was nearly knee deep. We finally found our dugout after walking miles it seemed [with] full pack, so slipping and sliding we went in the dugout. It had mud all over the floor and a big pool of water under the boards. After unpacking we went to bed or rather got on a bunk. Well, when the candle went out and all was still we got introduced to the trench rats and oh what a welcome they gave us. Never will I forget it or them.

Whether soldiers were living in trenches or assaulting German positions, artillery was a greater danger than bullets. So, trenches had bomb proofs to provide shelter from frequent artillery attacks. James Madison Marshall, brother of Roy Jackson Marshall, wrote their sister back in North Carolina, “Do not be uneasy about us, for our dugouts are fairly deep and safe and of course, bomb proof until hit by a bomb, or shell, then not always destroyed.”

By the time Americans arrived on the front, the use of poison chlorine gas was common. Soldiers on watch had to alert their comrades when gas was detected. A hanging artillery shell casing often served as a warning bell, but they also used special wooden rattles to signal the presence of gas. American soldiers wore protective masks modeled after those used by the British. These were always uncomfortable and sometimes did not work if they were used the wrong way.

Barbed wire protected both German and Allied trenches. When it was destroyed by artillery fire, front line soldiers repaired the wire entanglements at night. National Guardsman William F. Crouse, who served in the 105th Engineer Regiment, recalled what it was like to crawl out into no-man’s-land to string and repair barbed wire: “They had iron stakes that screwed into the ground [and] you would screw some here and stretch the barbed wire. Under the cover of darkness, it was relatively safe to move about and work but, when [the Germans] shot up those flare lights you had better be lying in that mud; you had better not be up. They would shoot up those flare lights and open up a machine gun on you.”

When troops went over the top, they usually fixed bayonets and moved out from their trenches in a series of organized waves. However, platoon sergeant Roby Yarborough of Lexington reported that no matter how well any attack was planned, it quickly broke down in the confusion of battle:

We were supposed to have a solid front to move forward at the same time, but it didn't last. . . . The air was filled with smoke, and dust, and fog to where you didn't have much chance to keep your sense of direction. I think that partially accounts for the disorder we had within the ranks. A few of us could stay together, but if we got maybe forty feet away from the other men we couldn’t see them.

Once in enemy trenches, fighting became little more than a deadly brawl with soldiers using rifles, pistols, bayonets, trench knives, clubs, and shovels to kill each other.

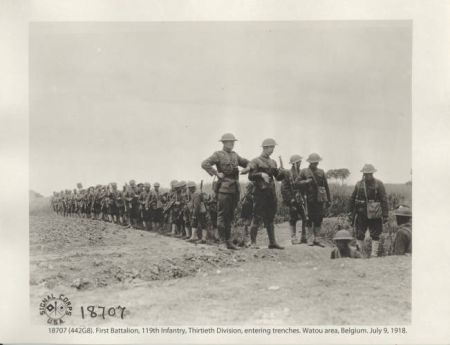

During World War I, American soldiers fought in fourteen battles in France and Belgium. North Carolinians in the 30th Division won lasting glory for breaking through the fabled Hindenburg Line and capturing the extensive Saint-Quentin tunnel complex on September 29, 1918. After the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, Ishan Barney Hudson of Winston-Salem expressed the feelings of many combat troops when he said, “May God refuse to me seeing ever another battle.”

At the time of this article’s publication, Tom Belton served as curator of militaria, politics, and society for the North Carolina Museum of History. Belton previously served as executive secretary of the Tar Heel Junior Historian Association.

Additional resources:

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI. NC Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm

"World War I." ANCHOR. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/world-war-i

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit, State Archives of NC. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm

Image credit:

US Army, Signal Corps. 1918. "First Battalion, 119th Infantry, Thirtieth Division, entering trenches. Watou area, Belgium, July 9, 1918." State Archives of North Carolina. Online at https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/first-battalion-119th-infantry-thirtieth-division-entering-trenches.-watou-area-belgium-july-9-1918/559135. Accessed 08/31/2012.

1 May 1993 | Belton, Tom