Women in the 1920s in North Carolina

Related Entries: Women; Roaring Twenties; Gertrude Weil

"A New Woman Emerges"

by Louise Benner

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2004.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

A woman of 1920 would be surprised to know that she would be remembered as a “new woman.” Many changes would enter her life in the next ten years. Significant changes for women took place in politics, the home, the workplace, and in education. Some were the results of laws passed, many resulted from newly developed technologies, and all had to do with changing attitudes toward the place of women in society.

A woman of 1920 would be surprised to know that she would be remembered as a “new woman.” Many changes would enter her life in the next ten years. Significant changes for women took place in politics, the home, the workplace, and in education. Some were the results of laws passed, many resulted from newly developed technologies, and all had to do with changing attitudes toward the place of women in society.

The most far-reaching change was political. Many women believed that it was their right and duty to take a serious part in politics. They recognized, too, that political decisions affected their daily lives. When passed in 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote. Surprisingly, some women didn’t want the vote. A widespread attitude was that women’s roles and men’s roles did not overlap. This idea of “separate spheres” held that women should concern themselves with home, children, and religion, while men took care of business and politics. North Carolina opponents of woman suffrage, or voting, claimed that “women are not the equal of men mentally” and being able to vote “would take them out of their proper sphere of life.”

Though slow to use their newly won voting rights, by the end of the decade, women were represented on local, state, and national political committees and were influencing the political agenda of the federal government. More emphasis began to be put on social improvement, such as protective laws for child labor and prison reform. Women active in politics in 1929 still had little power, but they had begun the journey to actual political equality.

With regard to education, North Carolina’s female high school students seldom expected to go to college. If they did, they usually attended a private college or Woman’s College in Greensboro (now UNC-G), where there were no male students. Most of the Woman’s College students became teachers or nurses, as these were considered suitable professions for women. North Carolina State College (now NCSU) enrolled its first woman student in 1921, but it was not until 1926 that N.C. State decreed, “A woman who completes work for a degree offered by the institution [can] be graduated.” In 1928 only twenty-one women were enrolled there.

With regard to education, North Carolina’s female high school students seldom expected to go to college. If they did, they usually attended a private college or Woman’s College in Greensboro (now UNC-G), where there were no male students. Most of the Woman’s College students became teachers or nurses, as these were considered suitable professions for women. North Carolina State College (now NCSU) enrolled its first woman student in 1921, but it was not until 1926 that N.C. State decreed, “A woman who completes work for a degree offered by the institution [can] be graduated.” In 1928 only twenty-one women were enrolled there.

The University of North Carolina opened housing to female graduate students in 1921, but they were not made welcome. The student newspaper headlined, “Women Not Wanted Here.” Few North Carolina women earned degrees during the 1920s. But times were changing, and each year more women earned college degrees.

At the beginning of the decade, most North Carolina women lived in rural areas without electricity. Imagine trying to keep food fresh without a refrigerator, ironing (no drip-dry clothing then) with an iron that had to be reheated constantly, cooking on a woodstove, going to an outside well for water, and always visiting an outhouse instead of a bathroom. Rural electrification did not reach many North Carolina homes until the 1940s.

Urban women found that electricity and plumbing made housework different, and often easier, with electrically run vacuum cleaners, irons, and washing machines. Electricity meant that people could stay up later at night, because electric lights were more efficient than kerosene lamps and candles. Indoor plumbing brought water inside and introduced a new room to clean—the bathroom.

Urban women found that electricity and plumbing made housework different, and often easier, with electrically run vacuum cleaners, irons, and washing machines. Electricity meant that people could stay up later at night, because electric lights were more efficient than kerosene lamps and candles. Indoor plumbing brought water inside and introduced a new room to clean—the bathroom.

In the United States in the 1920s, only about 15 percent of white and 30 percent of black married women with wage-earning husbands held paying jobs. Most Americans believed that women should not work outside the home if their husbands held jobs. As a result of this attitude, wives seldom worked at outside jobs. However, some married women in desperate need took jobs in textile mills.

By 1922 North Carolina was a leading manufacturing state, and the mills were hiring female floor workers. Cotton mills also employed a few nurses, teachers, and social workers to staff social and educational programs. These mills did not hire black women, however, because of segregation. As a consequence, white millworkers often hired black women as domestic and child-care workers. Fewer jobs were available in tobacco factories because most of their 1920s machinery was automated. The largest North Carolina tobacco manufacturers did employ both black and white women, but strictly separated workers by race and gender.

At the same time, public acceptance of wage-earning jobs for young unmarried women was growing. No longer being limited to work as “mill girls” or domestics, these women began to perform clerical work in offices and retail work in shops and department stores. It became acceptable for working girls to live away from their families. Some young married women worked until they had children. Working for wages gave women independence, and by 1930 one in four women held a paying job.

![Library of Congress. "Where there's smoke there's fire [192-?]."](/sites/default/files/New%20to%20upload/FlapperLOC.jpg) Despite increasing opportunities in employment and education, and the expanding concept of a “woman’s place,” marriage remained the goal of most young women. Magazine articles and movies encouraged women to believe that their economic security and social status depended on a successful marriage. The majority worked only until they married.

Despite increasing opportunities in employment and education, and the expanding concept of a “woman’s place,” marriage remained the goal of most young women. Magazine articles and movies encouraged women to believe that their economic security and social status depended on a successful marriage. The majority worked only until they married.

Working women became consumers of popular products and fashions. Women who would never tolerate the strong smells and stains of chewing tobacco or cigars began to smoke the new, and relatively clean, mild cigarettes. Cigarettes were advertised to women as a sign of modern sophistication, and the 1920s “flapper” is usually pictured with a cigarette in her hand.

Today the easily recognized image of the flapper symbolizes the 1920s for many people. The flapper—with her short skirts, short hair, noticeable makeup, and fun-loving attitude—represented a new freedom for women. The old restrictions on dress and behavior were being overthrown. Highly publicized flappers shortened their skirts, drank illegal alcohol, smoked, and otherwise defied society’s expectations of proper conduct for young women.

Is this glamorous and rebellious image of the flapper a true representation of the 1920s woman? Not entirely. In order to be a flapper, a woman had to have enough money and free time to play the part. College girls, unmarried girls living at home, and independent office workers most frequently presented themselves as flappers. However, the average woman did wear the fashions made popular by flappers. As often happens, unconventional clothing was gradually integrated into fashion and adopted at all income levels. Sears, Roebuck, and Company claimed that nine million families made purchases from its catalogs in 1925. The clothing sold through catalogs was based on high-fashion styles from Paris.

Flappers popularized slender, boyish fashions. Figures were flattened with undergarments. Hemlines, straight or uneven, gradually crept up, and waistlines dropped. High-fashion evening wear in tubular, sleeveless styles featured beading and fringe. Day dresses copied the evening lines, if not the trims. Short skirts were complemented by flesh-colored stockings worn with decorative shoes. Hair was cut close to the head and covered outdoors by the close-fitting cloche hat. It became respectable to wear makeup. Between 1920 and 1930, women’s appearance changed completely.

Women found their lives changed in more than appearance, however. Society now accepted that women could be independent and make choices for themselves in education, jobs, marital status, and careers. Women’s spheres had broadened to include public as well as home life. The “new woman” was on her way.

At the time of this article’s publication, Louise Benner worked as a curator of costume and textiles at the North Carolina Museum of History.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: Nineteenth Amendment. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/05/NineteenthAmendment.pdf

Grade 8: Women’s Rights and the North Carolina Constitution. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/WomensRightsandNCConstitution.pdf

Resources:

UNC, iBiblio: "Women's Suffrage Between the War": http://www.ibiblio.org/uncpress/ncbooks/suffrage/index.html

UNC Libraries: North Carolina and the Women's Suffrage Amendment

DocSouth, UNC: "Explore Women's History in North Carolina.": https://docsouth.unc.edu/highlights/women_nc.html

"The Flapper." ANCHOR. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/flapper

"The Constitution: The 19th Amendment." U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/amendment_19/ (accessed May 20, 2013).

Image Credits:

Library of Congress. "Suffrage Parade, Wash D.C." March, 1913. Located at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001704188/ (accessed March 5, 2012).

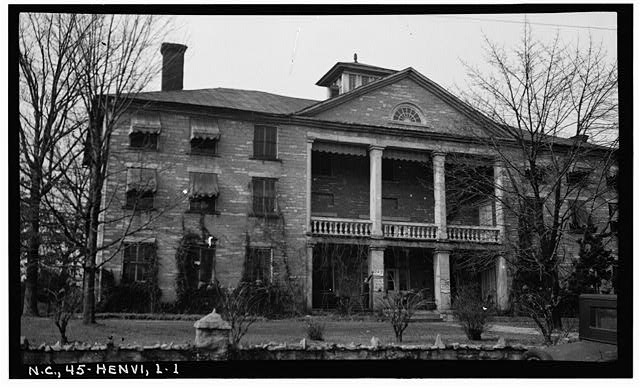

Library of Congress. "Historic American Buildings Survey, Stewart Rogers, Photographer February 20 1934 EAST ELEVATION (FRONT). - Judson College, Third Avenue & West Flemming Street, Hendersonville, Henderson County, NC, Women's College." Located at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/nc0256.photos.102283p/ (accessed March 5, 2012).

Library of Congress. "This group represents most of the workers in the Cape Fear Cotton Mills, except the very smallest. There were 5 or 6 apparently under 13. See North Carolina report. Location: Fayetteville, North Carolina." November 1914. Located at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ncl2004004145/PP/ (accessed March 5, 2012).

Library of Congress. "Where there's smoke there's fire [192-?]." http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2009616115/ (accessed March 5, 2012).

1 January 2004 | Benner, Louise