North Carolina Civil War Flags

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian 50:2 (spring 2011)

On July 3, 1863, the final, bloody day of the Civil War’s Battle of Gettysburg, a soldier from the 14th Connecticut Volunteers captured an enemy’s battle flag. The flag belonged to the 52nd Regiment North Carolina Troops, which included soldiers from almost a dozen counties. Part of Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew’s brigade, the 52nd suffered heavy losses that day in Pennsylvania: 46 men killed in action, 64 wounded, 140 wounded and captured, and 91 captured. The flag—which the U.S. War Department in Washington, D.C., returned to the Tar Heel State in 1905—now is part of the North Carolina Museum of History collection.

While many symbols represent the Civil War, few have evoked more emotion than flags. Even though North Carolina’s role and experience in the Civil War hold enormous historical importance, most modern Tar Heels remain unaware of all the flags associated with North Carolina and the Confederacy. The state’s Confederate troops carried and fought under four different kinds of flags: (1) state flags; (2) company flags; (3) national flags; and (4) battle flags. Today, these banners have become artifacts that help tell the story of the Civil War and those who fought it.

While many symbols represent the Civil War, few have evoked more emotion than flags. Even though North Carolina’s role and experience in the Civil War hold enormous historical importance, most modern Tar Heels remain unaware of all the flags associated with North Carolina and the Confederacy. The state’s Confederate troops carried and fought under four different kinds of flags: (1) state flags; (2) company flags; (3) national flags; and (4) battle flags. Today, these banners have become artifacts that help tell the story of the Civil War and those who fought it.

Before North Carolina withdrew from the Union on May 20, 1861, the state had no official flag. The State Convention in Raleigh had to address this need. On June 22 the convention approved an official North Carolina flag. During the Civil War, regiments from both North and South were organized at the state level. They carried numerical state regimental designations, such as the 21st North Carolina or the 21st New York. State flags became symbols of state pride when regiments displayed them on the march or carried them into battle.

In the early months of the war, volunteers joined units organized in their communities. Approximately 100 men made up each of these units, called companies. Companies frequently took names that identified their homes, such as the Clayton Yellow Jackets, the Forsyth Rifles, or the Rutherford Rifles. Ten companies completed a regiment of approximately 1,000 men. During elaborate ceremonies held before they left for war, companies often were presented with flags made by local women. Sometimes these flags had been sewn from the silk of women’s dresses, which made them more personal. For the soldiers who marched away to an uncertain future, company flags represented the love and support of family, friends, and communities.

As a new nation, the Confederate States of America needed a flag to illustrate its national identity. On March 4, 1861, the Provisional Congress of the Confederacy approved a national flag. This flag consisted of a red field with a white bar in the center, along with a blue canton (a square) in the upper left corner. Within the canton, a circle of white stars represented the states of the Confederacy. This flag became known as the “Stars and Bars.”

Unfortunately, in battle, the design created chaos. The flag could easily be mistaken for the United States flag, called the “Stars and Stripes.” In 1863 Confederate officials replaced the “Stars and Bars” with another national flag called the “Stainless Banner.” This flag consisted of a large white field with a Confederate battle flag as the canton. However, the large white field could be mistaken for a flag of surrender, so this design was replaced in March 1865. The third and final national flag looked like the Stainless Banner, with a red bar added vertically along the flag’s right edge (called the fly end).

At the Battle of First Manassas (also known as First Bull Run) in Virginia in July 1861, the close resemblance of the Stars and Bars to the Stars and Stripes on a smoke-covered battlefield created confusion and uncertainty over unit identities. The tragic result was “friendly fire,” as soldiers unknowingly shot at their own men. Because the national flag of the Confederacy had already been approved, leaders decided the army would adopt a separate flag, only to be carried in battle. Because it was not a national flag, the new battle flag never flew over government buildings or military installations during the Civil War. Many people today, however, believe it was the only flag of the Confederacy.

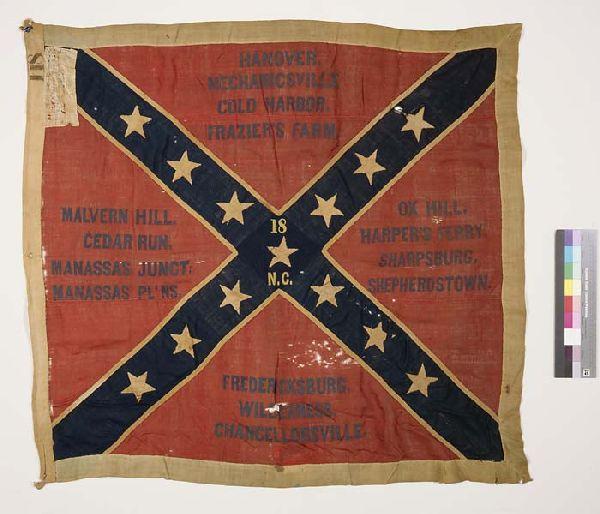

During a Civil War battle, troops fought in a line. The regimental colonel stood behind the center of the line, with the color guard and color-bearer placed directly in front of him. Due to the terrific battlefield noise caused by the firing of rifles and cannons, exploding shells, and screams of wounded and dying men, soldiers often heard few commands. So the colonel passed his orders on to the color-bearer with his battle flag. All of the troops in the battle line watched the colorbearer and followed his movements. If the colonel ordered the regiment forward, for example, the color-bearer raised his flag and moved forward.

Because of this role in leading the regiment, the color-bearer became one of the most important men on the battlefield—and a constant target for enemy soldiers. Men who carried the battleflag were chosen for their steadfastness and bravery. Eight men composed the color guard, which meant another soldier could quickly retrieve the flag if the man holding it went down. Carrying the flag into battle was a dangerous job, with tremendous casualty rates. But there was nevera shortage of volunteers. As the men went into combat, their battle flag became a visible symbol for all of the reasons they were willing to fight and die.

The North Carolina Museum of History has the largest collection of Confederate flags held by any state-operated museum in the South. Fred Olds, the original director of the Hall of History (now the Museum of History) made a special effort to locate surviving Tar Heel flags and secure them for the museum. The majority of the flags in the collection were received during his service as director. Over the years, the museum has acquired more flags through donations or purchases.

The public has never seen many of these banners, because each one needs conservation work. In recent years, Civil War reenactment groups such as the 26th North Carolina, Reactivated, and heritage organizations like the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) have given tens of thousandsof dollars for flag conservation. Once conserved, these flags can be placed in exhibits. Today,the Civil War flag collection ranks among the museum’s greatest historical treasures, reflecting North Carolina’s rich military heritage.

Image Credit:

[Battled Flag, 18th NCT]. 1863. Item H.1914.252.25. North Carolina Museum of History. (accessed June 12, 2015).

12 June 2015 | Belton, Tom