Ashe, John

24 Mar. 1725–24 Oct. 1781

John Ashe, colonial legislator, Stamp Act patriot, and army officer, was born at Grovely in New Hanover, now Brunswick County, the son of Elizabeth Swann and John Baptista Ashe. His father was a native of England, a lawyer, who settled in the Cape Fear region and served as a member of the governor's council. The elder Ashe, who died in 1734, provided in his will for a sound, liberal education, including Latin, Greek, and French, for his son. The son, a member of the Harvard class of 1746, although he did not graduate, entered professional life and settled on the Northeast Cape Fear River; there he built a fine plantation house, Green Hill, in which he had an excellent library. He served as colonel of the militia and in 1752 was elected to the assembly; in 1762 he became speaker of the house. He was described as an eloquent speaker, patriotic, and strong willed. A staunch patriot, he was a member of the committee of correspondence and of the committee of safety.

John Ashe, colonial legislator, Stamp Act patriot, and army officer, was born at Grovely in New Hanover, now Brunswick County, the son of Elizabeth Swann and John Baptista Ashe. His father was a native of England, a lawyer, who settled in the Cape Fear region and served as a member of the governor's council. The elder Ashe, who died in 1734, provided in his will for a sound, liberal education, including Latin, Greek, and French, for his son. The son, a member of the Harvard class of 1746, although he did not graduate, entered professional life and settled on the Northeast Cape Fear River; there he built a fine plantation house, Green Hill, in which he had an excellent library. He served as colonel of the militia and in 1752 was elected to the assembly; in 1762 he became speaker of the house. He was described as an eloquent speaker, patriotic, and strong willed. A staunch patriot, he was a member of the committee of correspondence and of the committee of safety.

When the outraged citizens of Wilmington were ordered by Great Britain to accept the Stamp Act, Ashe took a strong stand in opposition. He resigned his royal commission, was elected to the same rank by the people of New Hanover County, and became the first to accept a military commission at the hands of the people. Later, on the eve of the American Revolution, colonial Governor Josiah Martin took refuge in Fort Johnston on the Cape Fear. Rumor spread that the governor was preparing to reinforce Fort Johnston, whereupon Colonel Ashe sought to raise a regiment by the force of his character and by pledging his estate, which meant that the recruits took his promissory notes instead of pay. At the head of five hundred men, he attacked the fort and on 17 July 1775 reduced it to ashes. In this affair, he took the full responsibility upon himself and with his own hands applied the torch that burned the fort.

The council of safety met in October of 1775 and appointed Ashe, his brother Samuel, and Cornelius Harnett to speak to the people and explain to them the need for the military organization requested by the provincial congress. Ashe's rally to this cause was so creditable and successful that, for this and other services, the congress that met in Halifax on 4 Apr. 1776 promoted him to the rank of brigadier general.

Ashe's strength seems to have been in parliamentary debate and in the force of his eloquence, but the warmth of feeling and imagination required for the orator were unfavorable to the cool calculation and cautious observance of detail required by a sound military commander. So it is unfortunate that his name is most often connected with an affair showing his lack of skill and experience in military command, rather than with one portraying the patriotic oratory for which he was so well educated and adapted. Early in 1779 he was sent to Georgia with a large command by which Governor Richard Caswell hoped to reinforce General Benjamin Lincoln, then in the command of the Southern Army. Lincoln planned an all-out attack against the British and ordered Ashe to pursue the English leader, Colonel William Campbell, below the Savannah River and, deploying the whole army, to secure Georgia for the Continentals. It was necessary that Ashe hold his position in the sweeping attack. He crossed the river 25 Feb. 1779 and headed for Briar Creek, about forty-five miles below Augusta. He reached Briar Creek on the twenty-seventh and found the bridge destroyed by the enemy. Vast swamps surrounding the bridge area made this a most untenable position for Ashe. Before the bridge was repaired, the enemy sent a detachment back across the creek and circled to the rear of Ashe's troops. Some of his troops discovered the British about eight miles away and sent a message to warn Ashe, but it was intercepted. Delay in repairing the bridge, with unorganized observation parties and poorly armed troops, made retreat virtually impossible for the militia and Continentals under Ashe. The defeat was total and gave Georgia to the enemy. General Ashe was disgraced; his case was tried by a court martial at his own request. He was found free of any display of cowardice but was censured for his lack of foresight.

After his surprise and defeat, he made his way home. Two of his sons, Samuel and William, had been taken prisoner, and Wilmington had become a British garrison. In 1781, while in hiding, Ashe was betrayed to the enemy. He was made a prisoner in Wilmington at a place called Craig's "bull-pen," suffered a long confinement, and contracted smallpox. Paroled because of his extreme illness, he began to make his way to join his family at Hillsborough. He got no farther than Sampson Hall, the residence of Colonel John Sampson of Sampson County, where he died and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Ashe was married to his cousin, Rebecca Moore, sister of Judge Maurice Moore and General James Moore. To them were born four sons—William, Samuel, John, and A'Court, none of whom left children—and three daughters—Harriet, Eliza (whose husband, William H. Hill, was U.S. district attorney), and Mary (who married an Alston and whose son, Joseph, was governor of South Carolina from 1812 to 1814 and husband of Theodosia, the daughter of Aaron Burr).

This person enslaved and owned other people. Many Black and African people, their descendants, and some others were enslaved in the United States until the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in 1865. It was common for wealthy landowners, entrepreneurs, politicians, institutions, and others to enslave people and use enslaved labor during this period. To read more about the enslavement and transportation of African people to North Carolina, visit https://aahc.nc.gov/programs/africa-carolina-0. To read more about slavery and its history in North Carolina, visit https://www.ncpedia.org/slavery. - Government and Heritage Library, 2023

References:

Samuel A. Ashe, ed., Biographical History of North Carolina, vol. 4 (1906).

E. W. Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents (1854).

William S. Powell, James K. Huhta, and Thomas J. Farnham, eds., The Regulators in North Carolina (1971).

Selesky, Harold E and Thomson Gale (Firm). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution : Library of Military History (version 2nd ed). 2nd ed. Detroit M.I.: Charles Scribner's Sons : Thomson Gale. 2006. Accessed May 30, 2023 at https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofam0001unse_s6p1/page/n7/mode/2up.

James Sprunt, Chronicles of the Cape Fear River (1914).

John H. Wheeler, Historical Sketches of North Carolina (1851).

Additional Resources:

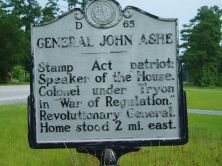

"General John Ashe." N.C. Highway Historical Marker D-65, N.C. Office of Archives & History. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-hig...(accessed January 30, 2013).

Lawrence Lee, The Lower Cape Fear in Colonial Days (1965)

John L. Cheney, comp., North Carolina Government, 1585-1979 (1981)

CSR Documents by Ashe, John, 1725-1781, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, UNC Libraries: https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/creators/csr10320

Image Credits:

"General John Ashe." N.C. Highway Historical Marker D-65, N.C. Office of Archives & History. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-hig...(accessed January 30, 2013).

1 January 1979 | Whiteside, Heustis P.