Gilmer, John Adams

4 Nov. 1805–14 May 1868

See also: Jeremy Francis Gilmer, brother.

John Adams Gilmer, state senator and U.S. and Confederate States congressman, was born near Alamance Church in Guilford County. He was the oldest of the twelve children of Robert and Anne Forbes Gilmer, both of whom were of Scot-Irish descent, their families having come from Ireland to North Carolina by way of Pennsylvania. His father, a farmer and wheelwright, and both of his grandfathers had fought in the Revolutionary War. As a boy, Gilmer worked on his father's farm in the summer and attended an old-field school in the winter. At seventeen he began to teach in the neighborhood, and at nineteen he entered Eli W. Caruthers's academy in Greensboro. After studying there for two years, he taught for three years in a grammar school in Laurens County, S.C. Returning to North Carolina in 1829, he read law in the office of Archibald D. Murphey and in 1832 was admitted to the bar. He soon built up a large and profitable practice, which enabled him to accumulate slaves and other property. During the same period he rose to local prominence, serving as chairman of the Greensboro town board and as solicitor of Guilford County. A zealous defender of slavery, he led in prosecuting two Wesleyan Methodist preachers for the dissemination of abolitionist propaganda and in rousing mobs that drove them from the state (1850–51). The 1860 census gave his occupation as both the law and agriculture and credited him with owning fifty-three slaves and an estate worth $112,000, more than six times as much as the average for the county.

John Adams Gilmer, state senator and U.S. and Confederate States congressman, was born near Alamance Church in Guilford County. He was the oldest of the twelve children of Robert and Anne Forbes Gilmer, both of whom were of Scot-Irish descent, their families having come from Ireland to North Carolina by way of Pennsylvania. His father, a farmer and wheelwright, and both of his grandfathers had fought in the Revolutionary War. As a boy, Gilmer worked on his father's farm in the summer and attended an old-field school in the winter. At seventeen he began to teach in the neighborhood, and at nineteen he entered Eli W. Caruthers's academy in Greensboro. After studying there for two years, he taught for three years in a grammar school in Laurens County, S.C. Returning to North Carolina in 1829, he read law in the office of Archibald D. Murphey and in 1832 was admitted to the bar. He soon built up a large and profitable practice, which enabled him to accumulate slaves and other property. During the same period he rose to local prominence, serving as chairman of the Greensboro town board and as solicitor of Guilford County. A zealous defender of slavery, he led in prosecuting two Wesleyan Methodist preachers for the dissemination of abolitionist propaganda and in rousing mobs that drove them from the state (1850–51). The 1860 census gave his occupation as both the law and agriculture and credited him with owning fifty-three slaves and an estate worth $112,000, more than six times as much as the average for the county.

Elected to the state senate as a Whig in 1846, Gilmer was reelected four times and served until 1856. Soon after entering the senate he gained a statewide reputation for eloquence when he spoke in favor of establishing a psychiatric hospital for people with mental illnesses. He also was one of the foremost advocates of the improvements program launched by the legislature in its 1848–49 session. In particular, he championed the North Carolina Railroad, helped to have it routed in an arc so it would pass through Greensboro, and raised money from private investors to supplement the state's subscription. While in the legislature, he resisted efforts to eliminate the freehold qualification for voters. The requirement was necessary, he argued, for preventing the undue taxation of land.

When the national Whig party disintegrated, Gilmer along with Zebulon Vance and other prominent North Carolina Whigs joined the American or Know-Nothing party. In 1856 he ran as the Know-Nothing candidate for governor, proposing the establishment of a partially state-owned bank and upholding his party's antiforeigner and anti-Catholic principles as the grounds upon which "honest men" might unite and save the country from sectional fanatics. He lost the election to the Democratic incumbent, Governor Thomas Bragg, by the fairly decisive margin of more than 12,000 votes.

In 1857 and again in 1859, Gilmer won election to Congress as the representative of the Fifth District. In the House he distinguished himself as a friend of the Union and a foe of both Northern and Southern extremists. He opposed the Buchanan administration's scheme for bringing about the admission of Kansas as a slave state under the Lecompton constitution. During the struggle over the House speakership in 1859–60, he tried to prevent the slavery issue from being raised. He was himself the speakership candidate of the "South Americans," the Know-Nothings of the South, who held the balance of power in the House, but he received no more than 36 votes. Despite his slave ownership and his proslavery record he was viewed by many Southern Democrats as little better than an abolitionist because of his moderate stand. After the House was organized, he was appointed chairman of the Committee on Elections.

In the crisis of 1860–61 Gilmer tried his best to head off secession and war. Because the Secessionists made much of Abraham Lincoln's supposed abolitionism, he wrote to Lincoln (10 Dec. 1860) and asked him to make a public statement clarifying his views on slavery. This the president-elect declined to do, but, impressed by his standing as a Southern Unionist, he invited Gilmer to visit him in Springfield, Ill. His object, he explained to William H. Seward, was "if, on full understanding of my position, he would accept a place in the cabinet, to give it to him." A further goal of Lincoln was to attract Southern support for his administration and counteract secessionism in the South. While sympathetic, Gilmer felt that a visit to Springfield "would not be useful" without a prior meeting of minds. On Seward's urging, Gilmer reconsidered Lincoln's invitation, but he finally turned it down. At about the same time, on 26 Jan. 1861, he pled for sectional compromise in one of the most moving speeches of his career. He sent thousands of copies of this speech to North Carolina to help defeat the proposal for a secession convention in the February referendum.

In the crisis of 1860–61 Gilmer tried his best to head off secession and war. Because the Secessionists made much of Abraham Lincoln's supposed abolitionism, he wrote to Lincoln (10 Dec. 1860) and asked him to make a public statement clarifying his views on slavery. This the president-elect declined to do, but, impressed by his standing as a Southern Unionist, he invited Gilmer to visit him in Springfield, Ill. His object, he explained to William H. Seward, was "if, on full understanding of my position, he would accept a place in the cabinet, to give it to him." A further goal of Lincoln was to attract Southern support for his administration and counteract secessionism in the South. While sympathetic, Gilmer felt that a visit to Springfield "would not be useful" without a prior meeting of minds. On Seward's urging, Gilmer reconsidered Lincoln's invitation, but he finally turned it down. At about the same time, on 26 Jan. 1861, he pled for sectional compromise in one of the most moving speeches of his career. He sent thousands of copies of this speech to North Carolina to help defeat the proposal for a secession convention in the February referendum.

After Lincoln's inauguration Gilmer continued to correspond with Seward, now secretary of state, and was influential in the shaping of Seward's conciliatory policy. He urged that the administration remove the federal garrisons from the seceded states so as to avoid a clash of arms, which he feared would precipitate secession in the upper South. Seward gave the impression that the government would withdraw its troops from Fort Sumter. When, instead, Lincoln sent his Sumter expedition, Gilmer was "deeply distressed" at the "madness" that now prevailed. On the day the fort was fired upon (12 Apr. 1861), he was taking the Union side in a public debate in the Stokes County courthouse. Six days later, in the Guilford County courthouse, he stood with other Greensboro leaders in calling upon the local militia company, the Guilford Grays, to defend the state against any and all invaders. When the North Carolina secession convention finally met the following month, he attended as a delegate and joined in the unanimous vote for a secession ordinance.

During the last year of the Civil War, Gilmer was a representative in the Confederate Congress, serving as a member of the Ways and Means Committee and as chairman of the Committee on Elections. He generally opposed extreme measures for the conduct of the war. In February 1865 he offered a peace and reconstruction plan according to which the Union and the Confederacy would keep their separate identities but would send representatives to an overall "American diet." In March, after William T. Sherman's army had entered North Carolina, Gilmer recommended that peace talks be undertaken with General Sherman. After the war he endorsed President Johnson's reconstruction program, and in 1866 he attended the Philadelphia National Union convention as a delegate.

Gilmer was a tall, sturdily built, commanding figure, with an open and friendly manner and an engaging sense of humor. On 3 Jan. 1832 he had married Juliana Paisley, the daughter of a leading Presbyterian minister and the granddaughter of a Revolutionary War officer. Their son, John Alexander (22 Apr. 1838–17 Mar. 1892), rose to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the Confederate army and served from 1879 to 1891 as a superior court judge. Of the elder Gilmer, John H. Wheeler, a contemporary, wrote: "The melancholy effects of the unhappy intestine war preyed heavily on his spirits, naturally elastic, and on his robust constitution, and so brought his life to a premature close." He died in Greensboro and was buried in the cemetery of the First Presbyterian Church, of which he had long been a member.

References:

Thomas B. Alexander and Richard E. Beringer, Anatomy of the Confederate Congress (1972).

Bettie D. Caldwell, comp., Founders and Builders of Greensboro (1925 [portrait]).

DAB, vol. 4 (1960).

Frontis W. Johnston, Papers of Zebulon Baird Vance, vol. 1 (1963).

North Carolina Biography vol. 1 (1941).

W. J. Peale, Lives of Distinguished North Carolinians (1898).

Sallie W. Stockard, History of Guilford County (1902).

John H. Wheeler, Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians (1884).

Additional Resources:

"Gilmer, John Adams, (1805 - 1868)." Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Washington, D.C.: The Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=G000217 (accessed March 28, 2013).

McCrady, Edward. "Hon. John A. Gilmer." Cyclopedia of eminent and representative men of the Carolinas of the nineteenth century. Madison, Wis.: Brant & Fuller. 1892. 151-152. https://archive.org/stream/cyclopediaofemin02mccr#page/150/mode/2up (accessed April 3, 2013).

Alderman, Ernest H. "Chapter 15: The Campaign of 1856." The North Carolina colonial bar. [Chapel Hill, N.C.] : University of North Carolina. 1913. https://archive.org/stream/northcarolinaco01aldegoog#page/n444/mode/2up (accessed April 3, 2013).

Image Credits:

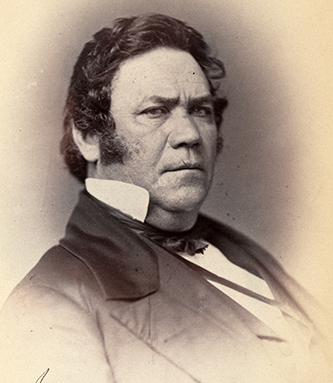

"[John A. Gilmer, Representative from North Carolina, Thirty-fifth Congress, half-length portrait]." McClees' gallery of photographic portraits of the senators, representatives & delegates of the thirty-fifth Congress. Washington, D.C.: McClees & Beck. [1859]. 146.http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010649185/ (accessed March 28, 2013).

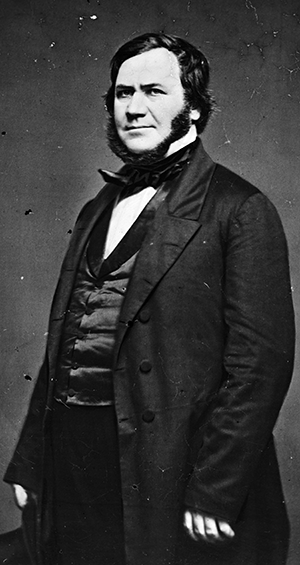

"Hon. J.A. Gilmer of N.C." Photograph. Between 1855 and 1865. Brady-Handy Collection. Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/brh2003004326/PP/ (accessed April 3, 2013).

1 January 1986 | Current, Richard N.