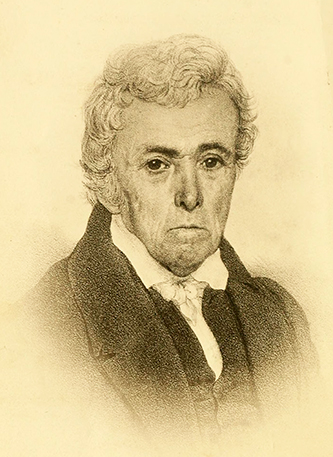

Martin, François-Xavier

17 Mar. 1762–10 Dec. 1846

François-Xavier Martin, editor, author, attorney, and jurist, was born in Marseilles, France. Little is known of his parentage and childhood, for while yet a teenager he sailed for the island of Martinique, where he worked for his uncle, a businessman. Near the end of the American Revolution, he appeared in New Bern, N.C., where he taught French, carried the mail, and worked in the print shop of James Davis. He then started a newspaper, titled the Noth-Carolina Gazette; or, New-Bern Advertiser, the earliest extant issue of which was dated 3 Nov. 1785. By 11 July 1787 the title had been changed to Martin's North-Carolina Gazette, and Martin appears to have owned the press. Within three years his name was dropped from the title, but he continued publishing the paper until at least 24 Feb. 1798.

François-Xavier Martin, editor, author, attorney, and jurist, was born in Marseilles, France. Little is known of his parentage and childhood, for while yet a teenager he sailed for the island of Martinique, where he worked for his uncle, a businessman. Near the end of the American Revolution, he appeared in New Bern, N.C., where he taught French, carried the mail, and worked in the print shop of James Davis. He then started a newspaper, titled the Noth-Carolina Gazette; or, New-Bern Advertiser, the earliest extant issue of which was dated 3 Nov. 1785. By 11 July 1787 the title had been changed to Martin's North-Carolina Gazette, and Martin appears to have owned the press. Within three years his name was dropped from the title, but he continued publishing the paper until at least 24 Feb. 1798.

Meanwhile, Martin prepared and published a variety of almanacs, pamphlets, books, and acts of the Assembly, and he edited and published several volumes of laws. Perhaps the best known of his early works was his revised edition in 1791 of The Office and Authority of a Justice of the Peace, and of Sheriffs, Coroners, &c. . . . His most valuable works, however, were published early in the new century, including The Public Acts of the General Assembly of North-Carolina (1804), containing laws passed from 1715 to 1803. Martin also translated and published several French novels, including three by Mme. Marie-Jeanne de Riccoboni. Both his newspaper and his books contained many errors, some attributable to his incomplete mastery of the English language, others to carelessness and poor proofreading.

After reading law, Martin was admitted to practice in 1789, and while not a good speaker, he became a skilled interpreter of the law. His research into the statutes impressed upon him the need for a history of the state, and as early as 1791 he began collecting documentary materials. In 1806, while representing New Bern in the House of Commons, he gained access not only to the state records in Raleigh but also to important private documents which he copied.

Martin's work in collecting and publishing the laws of North Carolina came to the attention of President James Madison, who in 1809 appointed him to a judgeship in the Mississippi Territory and the following year transferred him to the superior court in the Orleans Territory. In New Orleans, the native of France made a noteworthy contribution by synthesizing the tangled jurisprudence of three successive administrations—Spanish, French, and American. When Louisiana became a state in 1812, Martin was appointed its first attorney general, and three years later he took a seat on that state's supreme court. Joining the court at age fifty-three, he served for thirty-one years; during the last eleven years, he was presiding justice.

A bachelor and a prodigious worker, Judge Martin was not content just to hear and decide cases. For twenty-one years he carried on the arduous task of editing twenty-three volumes of cases heard by the superior court of the Orleans Territory and the supreme court of Louisiana. In the interim, he published a two-volume history each of Louisiana (1827) and North Carolina (1829).

The History of North-Carolina, from the Earliest Period would probably have been the first history of the state except for the interruption caused by the author's move to Mississippi and then Louisiana. The twenty-one-year delay in its completion enabled Hugh Williamson to earn the distinction of publishing the first history of North Carolina (1812). Martin, however, had carried his materials with him, and despite their damage aboard ship and subsequent attacks by "mice, worms, and the variety of insects of a humid and warm climate," they provided him with the sources necessary to complete his two-volume work in 1829. Martin's History had the strength of incorporating texts of documents not then in print but the weakness of careless copying as well as the absence of specific citations. His chapter on the Regulators, for instance, cited only "Records—Magazines—Gazettes."

The prolificity of his publications and his notoriety as a shrewd jurist made Martin one of the best-known judges in the country. He was elected to associate membership in the Academy of Marseilles in 1817 and received an honorary doctor of laws degree from Harvard College in 1841. Legends concerning his methods of interrogation abound; there are also numerous stories about his peculiar personal habits. Always a frugal man, he became more eccentric with age, grasping every dollar in sight and spending as little as a miser. He was even accused of refusing to pay the twenty-dollar cost of burying his body servant, who died on one of his circuit travels; he denied the obligation to pay the debt inasmuch as he did not live in the district of the burial, but he did offer one dollar, which he considered generous for the burial of a black servant.

Martin, whose eyesight was never good, became increasingly blind in the 1830s, and with the affliction, he was a pitiful figure. He lived in squalid quarters and dressed little better than a beggar. As he felt his way along the streets of New Orleans, his eyes closed, he was often taunted by mischievous children. He refused to give up his seat on the supreme court, however, and at age eighty-two traveled to his native Marseilles in hopes of having an operation on his eyes. He returned disappointed and retained his seat until the new state constitution was adopted in 1846. Married to his work throughout life, he died a few months later and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery. The old man amassed an estate of $396,000—a fortune in 1846—which in a holograph will dated two years earlier was left to a younger brother. The state contested the will, but the supreme court, on which he had sat for more than three decades, ruled that it was entirely within the realm of possibility that the aged man had used guides that enabled him to write the almost undecipherable one-page document.

François-Xavier Martin's influence on North Carolina was through the newspaper that he published for more than a decade, the books and pamphlets of laws that he compiled and published, and a history which, though poor by later standards, was the most objective study of the colonial period published to that time.

References:

DAB, vol. 6 (1933).

Charles Gayarre, Fernando de Lemos, Truth and Fiction: A Novel (1872).

William Wirt Howe, "Memoir of François-Xavier Martin," in François-Xavier Martin, The History of Louisiana. . . (1882).

H. G. Jones, For History's Sake (1966).

Edward Laroque Tinker, "Jurist and Japer: François-Xavier Martin and Jean LeClerc," Bulletin of the New York Public Library 39 (1935).

W. B. Yearns, "Francois X. Martin and His History of North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review 36 (1959).

Additional Resources:

"François-Xavier Martin (1762 - 1846)." Celebrating 200 Years: The Bicentennial of the Louisiana Supreme Court

1813-2013. Louisiana Supreme Court. http://www.lasc.org/Bicentennial/justices/martin_francois_xavier.aspx (accessed June 14, 2013).

"Francois-Xavier Martin." KnowLA The Encyclopedia of Louisiana. http://www.knowla.org/image/3139/ (accessed June 14, 2013).

Dugas, Katry. "An Immigrant's Journey to Wealth and Power: The Story of François-Xavier Martin." Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 50, no. 3 (Summer 2009). 321-340. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40646274 (accessed June 14, 2013).

Moréteau, Olivier. "François-Xavier Martin Revisited: Louisiana Views on Codification, Jurisprudence, Legal Education and Practice" Louisiana Bar Journal 60, no. 6 (April 2013). 475-479. http://www.academia.edu/3457024/Francois-Xavier_Martin_Revisited_Louisiana_Views_on_Codification_Jurisprudence_Legal_Education_and_Practice (accessed June 14, 2013).

Chiorazzi, Michael. "Francois-Xavier Martin: Printer, Lawyer, Jurist" Law Library Journal 80.1 (1988): 63-97. http://works.bepress.com/aallcallforpapers/63 (accessed June 14, 2013).

Image Credits:

"François-Xavier Martin." The history of Louisiana, from the earliest period. New Orleans: James A. Gresham. 1882. Frontispiece. https://archive.org/stream/historyoflouisia00mart#page/n9/mode/2up (accessed June 14, 2013).

1 January 1991 | Jones, H. G.