Blockade-Running

See also: Advance; Modern Greece.

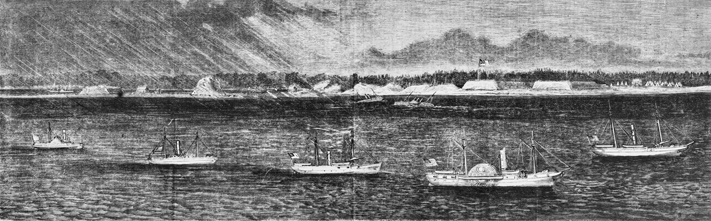

At the outset of the Civil War, the Union navy was faced with the monumental task of blockading the Confederate coast from Virginia to Texas, a coastline measuring almost 4,000 miles and containing 189 harbors. President Abraham Lincoln's proclamations of 19 and 27 Apr. 1861 made the blockade of the South complete, but only on paper. When the war started there were only 42 Union warships in commission, a far cry from the number required to close the Confederate ports. In May only two Federal vessels guarded the entire coast of North Carolina, and it was not until 20 July that the blockader Daylight took up station off the Cape Fear River. Twelve months later Adm. S. P. Lee had three cordons of Union ships guarding the mouth of the river. The first line was semicircular, reaching along the coast in either direction and far out to sea. In this cordon he placed sluggish, barely seaworthy vessels, whose orders were not to give chase but to signal the position of the blockade-runners to the faster ships patrolling in the second group or to the few cruisers even farther out. Still, he found it difficult to prevent ships from slipping through the blockade.

Wilmington, situated 570 miles from Nassau and 674 miles from Bermuda, was ideally situated for blockade-running. Located 28 miles up the Cape Fear River, it was free from enemy bombardment as long as the forts at the mouth of the river remained in Confederate hands. Moreover, Smith Island and Frying Pan Shoals jutted out into the Atlantic Ocean for approximately 25 miles, which made guarding Cape Fear's two navigable entrances very difficult. A fleet patrolling the two channels was required to cover a 50-mile arc and at the same time stay out of range of Confederate shore batteries. Protecting New Inlet, the passage preferred by most vessels, was massive Fort Fisher.

Few southerners were engaged in the business of blockade-running. It was monopolized by English and Scottish merchants who had ships and capital to invest in this hazardous but lucrative trade. British firms dispatched both luxury items and war matériel to the West Indies in regular merchant ships for transfer to blockade-runners, which would arrive in port loaded with cotton. With the South's leading staple crop selling for around 3 cents a pound in the Confederacy and 45 cents to one dollar a pound in Europe, enormous profits were to be made. On only eight trips through the blockade the British steamer Banshee, the first steel-hulled ship to cross the Atlantic, earned for its stockholders 700 percent profit.

After experiencing the tribulations of purchasing supplies from privately owned blockade-runners, North Carolina governor Zebulon B. Vance sent agents to England to purchase a steamer. They contracted for the Advance, which from 26 June 1863, the date of its maiden voyage to Wilmington, until its capture at sea a little over a year later, contributed much to North Carolina's war effort.

References:

Dawson Carr, Gray Phantoms of the Cape Fear: Running the Civil War Blockade (1998).

Thomas E. Taylor, Running the Blockade: A Personal Narrative of Adventures, Risks, and Escapes during the American Civil War (1896).

Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running during the Civil War (1988).

1 January 2006 | Barrett, John G.