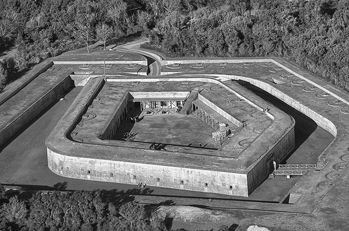

Fort Macon

In the years after the War of 1812, the U.S. military constructed a chain of permanent fortifications to defend its harbors and ports against the threat of foreign invasion. One of the forts was built between 1826 and 1834 on the eastern point of Bogue Banks to guard Old Topsail Inlet (Beaufort Inlet), the entrance to Beaufort Harbor. It was named in honor of Nathaniel Macon (1758-1837), a U.S. congressman, senator, and leading Republican statesman of North Carolina.

Active garrisons occupied Fort Macon in 1834-36, 1842-44, and 1848-49. During the period 1841-46 engineers made structural improvements to the fort's defenses. On 14 Apr. 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War, local militia forces from Morehead City and Beaufort, commanded by Capt. Josiah Pender, occupied Fort Macon in the name of the state without bloodshed. Throughout that year the fort was armed and occupied by North Carolina Confederate soldiers in preparation for an eventual Union attack.

In 1862 the Union army of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside launched a campaign on the North Carolina coast, intending to capture Fort Macon and Beaufort Harbor. Forces under Brig. Gen. John G. Parke took possession of Morehead City on 23 March and captured Beaufort three days later without resistance. Five artillery companies of North Carolina troops were garrisoned at Fort Macon. On 23 March, the fort's commander, Col. Moses J. White, who possessed 450 men and 54 heavy guns, refused a demand to surrender.

On 28 March Parke established siege positions within a half mile of the fort. He made a final demand for the fort's surrender, which White rejected on 24 April. Early the next morning Parke's batteries opened fire on Fort Macon, a bombardment that lasted 11 hours. The Union rifled cannons carried the day. This was only the second time in history that rifled artillery had bombarded a masonry fort, and it graphically demonstrated the growing obsolescence of forts as a means of defense. Parke's rifled cannons required only a few hours to crack Fort Macon's walls and threaten one of its gunpowder magazines.

Colonel White had no choice but to capitulate, which he did at 4:30 p.m. on 25 April. Arrangements for the surrender were completed the following morning, and Union forces formally occupied the badly damaged fort. The Confederates lost 7 killed and 18 wounded; Union losses were 1 killed and 3 wounded. The soldiers in the Confederate garrison were paroled and released.

Union forces repaired the damage to Fort Macon and used it for the remainder of the Civil War. During Reconstruction, the U.S. Army occupied the fort continuously until 1877, using it as a prison. In 1898 the fort was regarrisoned for the Spanish-American War, and in 1903 the U.S. Army abandoned it in the belief that it would never again be needed. It was not used in World War I, and in 1923 the Fort Macon Military Reservation was among several other abandoned forts and military posts that the War Department sold off as surplus property. But as a result of public and political pressure within North Carolina, the reservation was deeded to the state by a congressional act in June 1924 for use as a public park.

Fort Macon was the second area acquired by North Carolina for public use in what has grown into the present system of state parks. During the Great Depression, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp restored the fort and constructed recreational facilities. On 1 May 1936 Fort Macon State Park officially opened as the first developed, functioning park in North Carolina. The park was instantly popular, and the Works Progress Administration established a public beach at the site in the early 1940s.

When the United States entered World War II, the old fort went to war once again. On 21 Dec. 1941 Coast Artillery troops occupied the park for military defense purposes. By November 1944, when German U-boat activities off the North Carolina coast had subsided, the fort was deactivated. The army terminated its lease on 1 Oct. 1946, and the property was once again returned to North Carolina and resumed its former role as a state park.

References:

Paul Branch, Fort Macon: A History (1999).

Branch, The Siege of Fort Macon (1982).

Emanuel R. Lewis, Seacoast Fortifications of the United States: An Introductory History (1970).

Additional Images:

1 January 2006 | Branch, Paul, Jr.