Rosenwald Fund

From the 1910s through the 1930s, the philanthropic Julius Rosenwald Fund was a major force in North Carolina education. Its matching grants aided in the construction of more than 800 public school buildings for African American children and helped found the University of North Carolina Press in Chapel Hill.

From the 1910s through the 1930s, the philanthropic Julius Rosenwald Fund was a major force in North Carolina education. Its matching grants aided in the construction of more than 800 public school buildings for African American children and helped found the University of North Carolina Press in Chapel Hill.

Soon after becoming president of Sears, Roebuck and Company in 1909, Julius Rosenwald of Chicago became interested in black education, influenced in part by the book Up from Slavery, by African American educator Booker T. Washington of Alabama's Tuskegee Institute. Rosenwald met Washington in 1911 and soon became a trustee of Tuskegee. When Rosenwald earmarked his first $25,000 in 1912 for black colleges and preparatory academies, Washington asked to use a small sum for grants to black communities near Tuskegee for building rural elementary schools. Rosenwald consented, with the stipulation that each community must match the gift.

By Washington's death in 1915, Rosenwald had given matching funds to around 80 schools in a three-state area. One of these was a two-teacher school in North Carolina's Chowan County, completed in October 1915. The black community contributed $486, the white community and school system added $836, and Rosenwald gave $300. Such results spurred him to formally establish the Julius Rosenwald Fund two years later. The Tuskegee staff administered the fund until 1920, when the volume of applications and school-building projects led Rosenwald to set up an office in Nashville, Tenn. To run the program, he hired Samuel Leonard Smith, a school administrator who also had expertise in country schoolhouse design.

Public funds generally covered about half the cost of a school building, with the remainder divided equally between local, private contributions and the Rosenwald Fund. North Carolina led the South in the number of Rosenwald school buildings erected (813 of the 5,300 total), largely due to the efforts of leaders such as Nathan Carter Newbold, the state's director of black education. With 46 schools, Halifax County had by far the greatest number of schools in a single county built with Rosenwald funds.

In the late 1920s, Rosenwald Fund administrators began to expand their efforts, financing projects such as hospitals, libraries, and publishers of reports and texts on southern social and educational problems. Rosenwald funding helped establish the University of North Carolina Press in Chapel Hill, the South's first academic press.

Most Rosenwald schools continued to operate across the state until consolidation and racial desegregation in the 1960s closed their doors. A few, such as those in Zebulon and Wilkesboro, were still operational schools in the early 2000s, while most of these remaining historic landmarks serve as community centers, homes, and businesses. Extant Rosenwald schools adapted to other purposes include senior citizens' housing in Asheboro, the Raleigh Catholic Diocese offices near Smithfield, and the Town Hall at Princeville.

Educator Resources:

Grades K-8: https://www.ncpedia.org/rosenwald-schools-helping-communities-k-8

References:

Edwin R. Embree and Julia Waxman, Investment in People: The Story of the Julius Rosenwald Fund (1949).

Thomas W. Hanchett, "The Rosenwald Schools and Black Education in North Carolina," NCHR 65 (October 1988).

James L. Leloudis, Schooling the New South: Pedagogy, Self, and Society in North Carolina, 1880-1920 (1996).

Additional Resources:

Historical resources related to NC Rosewald Fund Schools, from NC Digital Collections.

Embree,Edwin R. Julius Rosenwald Fund: Review of Two Decades 1917-1936. Chicago. 1936. https://archive.org/stream/juliusrosenwaldf033270mbp#page/n7/mode/2up (accessed August 29, 2012).

Brown, Claudia R. "A Survey of North Carolina's Rosewald Schools." N.C. State Historic Preservation Office. February 10, 2003. http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/rosenwald/rosenwald.htm (accessed August 29, 2012).

Eckholm, Erik. "Black Schools Restored as Landmarks." The New York Times. January 14, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/15/us/15schools.html (accessed August 29, 2012).

"The Rosenwald Rural School Building Program." National Trust for Historic Preservation. http://www.preservationnation.org/travel-and-sites/sites/southern-region/rosenwald-schools/history/ (accessed August 29, 2012).

"Julius Rosenwald Fund records, 1920-1948." Amistad Research Center, Tulane University. http://www.amistadresearchcenter.org/archon/?p=collections/controlcard&id=68 (accessed August 29, 2012).

McCormick, J. Scott. "The Julius Rosenwald Fund." The Journal of Negro Education 3. No. 4. October 1934. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2292184 (accessed August 29, 2012).

"Guide to the Julius Rosenwald Papers 1905-1963." Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.ROSENWALDJ (accessed August 29, 2012).

Image Credits:

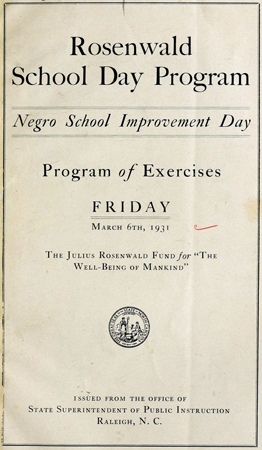

Cover of "Rosenwald School Day Program." Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction. Raleigh, N.C. 1931. https://archive.org/stream/rosenwaldschoold00nort#page/n1/mode/2up

1 January 2006 | Johnson, K. Todd