Treasurer

Treasurer was one of seven "chief officers" whom the Lords Proprietors intended to manage the province of North Carolina. The treasurer, as envisioned in the Fundamental Constitutions of 1669, was to deal with "all matters that concern the public revenue and treasury" and was to be aided by 6 counselors (undertreasurers) and 12 assistants (auditors). This office, like others in the colony, was slow to mature. Early governors acted as their own treasurers due to insufficient revenues until the staggering debts accrued from the Cary Rebellion and the Tuscarora War necessitated a more efficient system for raising taxes. Accordingly, in 1711 the governor and his council appointed treasurers for each of the seven precincts of the province. Three years later, the Lower House of the Assembly joined the Upper House and Governor Edward Hyde named Edward Moseley as treasurer of North Carolina and overseer of all precinct treasurers. Moseley, possibly the most able politician of his era, held the posts from 1714 to 1735. He returned in 1735 as treasurer for the southern district of North Carolina and remained in that position until his death in 1749, sharing what had once been a unified office with William Downing (1735-39), treasurer of the northern district. Eleazer Allen (1749-50), John Starkey (1750-65), and John Ashe (1765-75) succeeded Moseley in the south, while Thomas Barker (1748-52), John Haywood (1752-64), and Joseph Montford (1764-75) followed Downing in the north.

Treasurer was one of seven "chief officers" whom the Lords Proprietors intended to manage the province of North Carolina. The treasurer, as envisioned in the Fundamental Constitutions of 1669, was to deal with "all matters that concern the public revenue and treasury" and was to be aided by 6 counselors (undertreasurers) and 12 assistants (auditors). This office, like others in the colony, was slow to mature. Early governors acted as their own treasurers due to insufficient revenues until the staggering debts accrued from the Cary Rebellion and the Tuscarora War necessitated a more efficient system for raising taxes. Accordingly, in 1711 the governor and his council appointed treasurers for each of the seven precincts of the province. Three years later, the Lower House of the Assembly joined the Upper House and Governor Edward Hyde named Edward Moseley as treasurer of North Carolina and overseer of all precinct treasurers. Moseley, possibly the most able politician of his era, held the posts from 1714 to 1735. He returned in 1735 as treasurer for the southern district of North Carolina and remained in that position until his death in 1749, sharing what had once been a unified office with William Downing (1735-39), treasurer of the northern district. Eleazer Allen (1749-50), John Starkey (1750-65), and John Ashe (1765-75) succeeded Moseley in the south, while Thomas Barker (1748-52), John Haywood (1752-64), and Joseph Montford (1764-75) followed Downing in the north.

In 1776 the new state of North Carolina required all treasurers to be appointed with the approval of both the House of Commons (formerly the House of Burgesses) and the recently appointed Senate and banned all receivers of public moneys from sitting in the General Assembly or participating in the government. In 1784 the office of treasurer, then consisting of seven district treasurers, was reduced to one officeholder with a two-year term; he was placed on salary, without commission, and his office was moved from Edenton to Hillsborough, a more central location. Memucan Hunt was the first person to serve as singular treasurer of the state. In 1795 the treasury was relocated to the new capital city of Raleigh. At the same time, many of the treasurer's record-keeping functions were transferred to the comptroller-general, who was empowered to keep "distinct records" for all receivers of public moneys and to have these available at all times for inspection by the legislature.

In 1776 the new state of North Carolina required all treasurers to be appointed with the approval of both the House of Commons (formerly the House of Burgesses) and the recently appointed Senate and banned all receivers of public moneys from sitting in the General Assembly or participating in the government. In 1784 the office of treasurer, then consisting of seven district treasurers, was reduced to one officeholder with a two-year term; he was placed on salary, without commission, and his office was moved from Edenton to Hillsborough, a more central location. Memucan Hunt was the first person to serve as singular treasurer of the state. In 1795 the treasury was relocated to the new capital city of Raleigh. At the same time, many of the treasurer's record-keeping functions were transferred to the comptroller-general, who was empowered to keep "distinct records" for all receivers of public moneys and to have these available at all times for inspection by the legislature.

The office of treasurer, in the process, had lost its political significance and had become what it was originally intended to be: a fiscal office. The state constitution of 1868 changed the term of the treasurer to four years and made it a publicly elected post. North Carolina's state treasurers have generally been diligent overseers of the public money, avoiding political or fiscal scandal. The modern office, with the state's previously modest budget growing to more than $17 billion annually and its trust funds reaching about $30 billion, is a far cry from the simple accounting office of earlier times. The treasurer is a member of the Council of State and works closely with the governor on all fiscal and budgetary matters. The officeholder is also the state's banker, investment officer, administrator of governmental employee retirement and benefit systems, and official in charge of helping local governments maintain success in fiscal matters.

References:

John L. Cheney Jr., ed., North Carolina Government, 1585-1974: A Narrative and Statistical History (1981).

Charles L. Raper, North Carolina: A Study in English Colonial Government (1904).

Additional Resources:

North Carolina Department of State Treasurer official website: http://www.nctreasurer.com/

Biennial report of the Treasurer of North Carolina. 1920-1976. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/biennial-report-of-the-treasurer-of-north-carolina-1974-1976/2682557 (accessed September 18, 2012).

State Treasurer's annual report to the people of North Carolina. 1996-2010. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/state-treasurers-annual-report-to-the-people-of-north-carolina-2009-2010/2346298 (accessed September 18, 2012).

Image Credits:

E.G. Williams and Brothers. "Engraving, Accession #: H.19XX.318.89." 1900. North Carolina Museum of History.

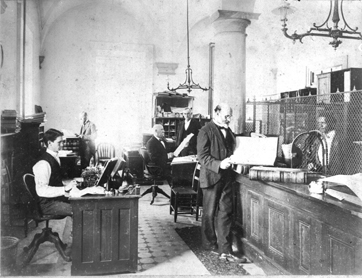

"N.2002.6.32." State Treasurer's Office, State Capitol building, Raleigh, NC, 1890s. From the General Negative Collection, North Carolina State Archives. https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/2431905310/ (accessed September 18, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Towles, Louis P.