Tuscarora Indians

by Thomas C. Parramore, 2006; Revised November 2022.

Additional research provide by George Stevenson, Harry L. Thompson, and Louis P. Towles.

See also: NCpedia articles related to the Tuscarora Indian War

Tuscarora Indians occupied much of the North Carolina inner Coastal Plain at the time of the Roanoke Island colonies in the 1580s. They were considered the most powerful and highly developed tribe in what is now eastern North Carolina and were thought to possess mines of precious metal. White settlers on Albemarle Sound fought sporadically with the Tuscarora from 1664 to 1667, the conflict apparently begun by the encroachment of a group of refugee Virginia Quakers on lands claimed by the tribe. Whites thereafter avoided further encroachment, recognizing the west side of Chowan River as Tuscarora country until after 1700. (A fur-trading post at the mouth of Salmon Creek, however, operated by mutual consent throughout the period as amonopoly and source of income for Carolina governors.)

Tuscarora Indians occupied much of the North Carolina inner Coastal Plain at the time of the Roanoke Island colonies in the 1580s. They were considered the most powerful and highly developed tribe in what is now eastern North Carolina and were thought to possess mines of precious metal. White settlers on Albemarle Sound fought sporadically with the Tuscarora from 1664 to 1667, the conflict apparently begun by the encroachment of a group of refugee Virginia Quakers on lands claimed by the tribe. Whites thereafter avoided further encroachment, recognizing the west side of Chowan River as Tuscarora country until after 1700. (A fur-trading post at the mouth of Salmon Creek, however, operated by mutual consent throughout the period as amonopoly and source of income for Carolina governors.)

A considerable fur trade with the Tuscarora began to develop in Virginia perhaps as early as the 1650s, and the Tuscarora became for a time a formidable presence in Virginia affairs. About 1701 Virginia began tolerating white encroachment on Indian lands west of Blackwater River, and the Chowan frontier immediately dissolved. Whites began pushing into lands of the Meherrin tribe, probably also Iroquoian and understood to be clients of the Tuscarora. The Tuscarora Upper Towns, those under the sway of Chief Tom Blount and occupying sites along the upper Neuse, Tar, and Roanoke Rivers, had sufficiently profitable relations with the whites to accept the new situation as long as they were not directly threatened. The Lower Towns, on the lower Neuse River and the Catechna (now Contentnea) Creek, led by Chief Hancock, were less disposed to do so. Importuned by small coastal tribes who were harassed by white settlements from Bath to New Bern between 1701 and 1711, Hancock and the Lower Towns in September 1711 staged what was evidently intended as a warning attack on white settlements.

The wanderings of Christoph von Graffenried and John Lawson in Tuscarora territory proved to be the flash point. The two men were taken hostage by the Tuscarora in September 1711, and Lawson was subsequently put to death. The brutal and swift English response soon developed into the full-scale Tuscarora War, during which successive expeditions of whites and non-Tuscarora Indians from South Carolina in 1712 and 1713 took on Hancock’s forces. Hancock and his people built and employed forts as part of their defensive strategy. The Tuscarora forts were built after 22 Sept. 1711, when a surprise attack upon the colonists on the Cape Fear River killed many settlers. Between October and December 1711, the Tuscarora, expecting a counterattack, turned their living areas into forts and withdrew their families, their crops, and their animals into these structures. Although not unlike European forts, the Tuscarora structures were variations of their circular and square palisade defense perimeters that predated the arrival of the whites. Probably due to the influence of the Europeans, the Tuscarora added thistle bushes outside fort walls and trenches inside the palisades, and at least one fort, Fort Neoheroka, possessed a strong redoubt to cover its entrance.

In late December 1711, Col. John ‘‘Jack’’ Barnwell, with 366 Indians and 30 white militia, marched over 300 miles from South Carolina to the aid of the North Carolinians fighting the Tuscarora. In January 1712 his command besieged and captured Fort Narhantes, 20 miles from New Bern, killing or taking prisoner nearly 400 Indians. Barnwell, with the aid of approximately 150 North Carolina militia, then moved against the larger and better-prepared Fort Hancock on Catechna Creek. An uncoordinated assault in early March failed, and Barnwell withdrew until 7 April, when he again moved against Fort Hancock. This time he approached the fort cautiously, over the course of ten days, by siege trenches. When his men were within 11 yards of the palisades, he ordered the space between the trenches and the walls to be filled by a ‘‘great quantity’’ of lightwood that he intended to set on fire in order to burn the palisades. Others of his command began bombarding Catechna with cannon. At this point, the Indians threatened to kill their white captives, and Barnwell agreed to a peace that required the Tuscarora to cede all territory between the Neuse and the Cape Fear Rivers. He and his Indians then returned to South Carolina.

In early 1713 South Carolina sent James Moore at the head of another expedition of whites and Indian allies aimed at destroying the Tuscarora. The last great stand of the Tuscarora took place at Fort Neoheroka on 20–23 Mar. 1713. Fort Hancock had been built according to state-of-the-art European ideas under the direction of a freedom-seeking South Carolina enslaved man named Harry, and Fort Neoheroka may have been a product of the same direction. A marsh to the south offered access to the fort only along a narrow ridge. The fort’s earthen walls (with loopholes for firing), topped by tall palisades of logs angled against still taller blockhouses, were surrounded by a moat and trenches; within were second walls and underground bunkers for noncombatants.

Moore’s men overran the trenches and raised a blockhouse and battery near the walls high enough to permit firing into Fort Neoheroka. On 20 March the attackers dug a tunnel to a portion of the outer wall and tried to blow it apart, but the effort failed because of defective powder. A subsequent charge carried part of the outer works and made it possible to set fire to a blockhouse and other parts of the fort. Still, three days of desperate hand-to-hand fighting were required for the South Carolinians to gain control, the defenders showing themselves, according to Baron von Graffenried, ‘‘unspeakably brave. . . . Wounded savages . . . on the ground still continued to fight. There were about 200 who were burned up in a redoubt and . . . in all about 900, including women and children were dead and captured.’’ Moore had 151 casualties, including 47 killed. This action ended the war-making capacity of the Tuscarora.

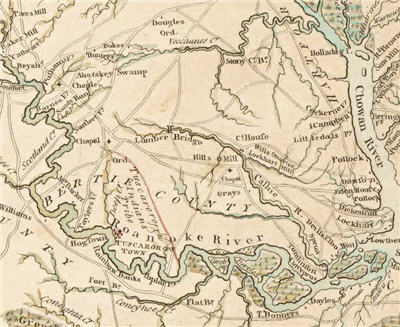

Tom Blount’s Upper Town Tuscarora, who had aided the European settlers in the war and even handed over Chief Hancock to the whites toward its close, were rewarded with a reservation. Lands on the north side of the Roanoke River between Quitsna Swamp and Deep Creek in southwestern Bertie County were secured in 1717 for this purpose. (An earlier reserved tract between the Neuse and Pamlico Rivers had proved unsatisfactory to Blount and his people.) The location of the reservation is shown on Moseley’s map of 1733, Collett’s map of 1770, and Price and Strother’s 1808 map, where it is assigned its popular name, Indian Woods Reservation.

The Tuscaroras who had opposed the settlers removed to Niagara County, N.Y., to join the Five Nations, thereafter the Six Nations. After several legal exchanges, the Tuscarora executed a deed to the state in 1831 extinguishing their title, right, and interest in the North Carolina land. Some 645 families or clans of Tuscaroras remained in the South, however, migrating to other parts of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. Their descendants eventually came together and reformed into four communities in and around Robeson County—the Tuscarora Nation East of the Mountain, the Tuscarora Tribe of North Carolina, the Southern Band Tuscarora Indian Tribe, and the Tuscarora Nation of North Carolina—none of which, as of the early 2000s, was officially recognized by the state of North Carolina.

References:

Thomas C. Parramore, "The Tuscarora Ascendancy," NCHR 59 (October 1982).

Parramore, "With Tuscarora Jack on the Back Path to Bath," NCHR 64 (April 1987).

Herbert J. Paschal Jr., "The Tuscarora Indians in North Carolina" (M.A. thesis, UNC-Chapel Hill, 1953).

Image credits:

Collett, John. 1770. "Compleat map of North-Carolina from an actual survey." North Carolina Collection Gallery, UNC. Online at: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/ncmaps,467. Accessed 11/2011. Note: Image in this entry is only a small section of the larger image, illustrating the location of the Tuscarora Indians as depicted on the map.

1 January 2006 | Parramore, Thomas C. ; Stevenson, George, Jr.; Thompson, Harry L.; Towles, Louis P.