Convention of 1789

North Carolina held a ratification convention in Fayetteville during 16-23 Nov. 1789 to debate for the second time whether to accept the U.S. Constitution and join the new federal Union. After the previous state convention at Hillsborough had decided in 1788 neither to ratify nor reject the Constitution, its staunch Federalist defenders pressured the General Assembly into resubmitting the question to the electorate. The Federalists waged such an effective campaign prior to the 1789 elections that their Anti-Federalist opponents secured less than one-third of the 272 seats at the Fayetteville convention. The Federalist triumph marked a rapid reversal of fortune for a group so badly outnumbered the previous year at Hillsborough.

North Carolina held a ratification convention in Fayetteville during 16-23 Nov. 1789 to debate for the second time whether to accept the U.S. Constitution and join the new federal Union. After the previous state convention at Hillsborough had decided in 1788 neither to ratify nor reject the Constitution, its staunch Federalist defenders pressured the General Assembly into resubmitting the question to the electorate. The Federalists waged such an effective campaign prior to the 1789 elections that their Anti-Federalist opponents secured less than one-third of the 272 seats at the Fayetteville convention. The Federalist triumph marked a rapid reversal of fortune for a group so badly outnumbered the previous year at Hillsborough.

Many factors contributed to this dramatic shift in public opinion. When the popular George Washington was unanimously elected president of an apparently ordered, stable government in early 1789, many Anti-Federalist fears about unbridled federal power were effectively dispelled. Influential Federalists controlled most of the state's newspapers, which they now used vigorously to support ratification and discredit their opponents. Moreover, Anti-Federalist opposition declined rapidly in May 1789, when James Madison, distinguished architect of the U.S. Constitution, handed Congress a proposed Bill of Rights in the form of constitutional amendments. These amendments neutralized the strongest objections of the opponents of ratification, who had long sought such guarantees of individual liberties as a condition for their support.

By the time the ratification convention opened on 16 November in Fayetteville, the major positions on ratification had already been thoroughly explored, and the outcome of the convention was assured. The Federalists now saw it as their task to negotiate a few compromises and "backstairs bargains," hoping to maximize support behind them. The opposing parties agreed to lay before Congress five mutually acceptable amendments, not covered under the proposed Bill of Rights, that would placate lingering demands for further limits on congressional taxing power and on the enlistment terms for soldiers, among other issues.

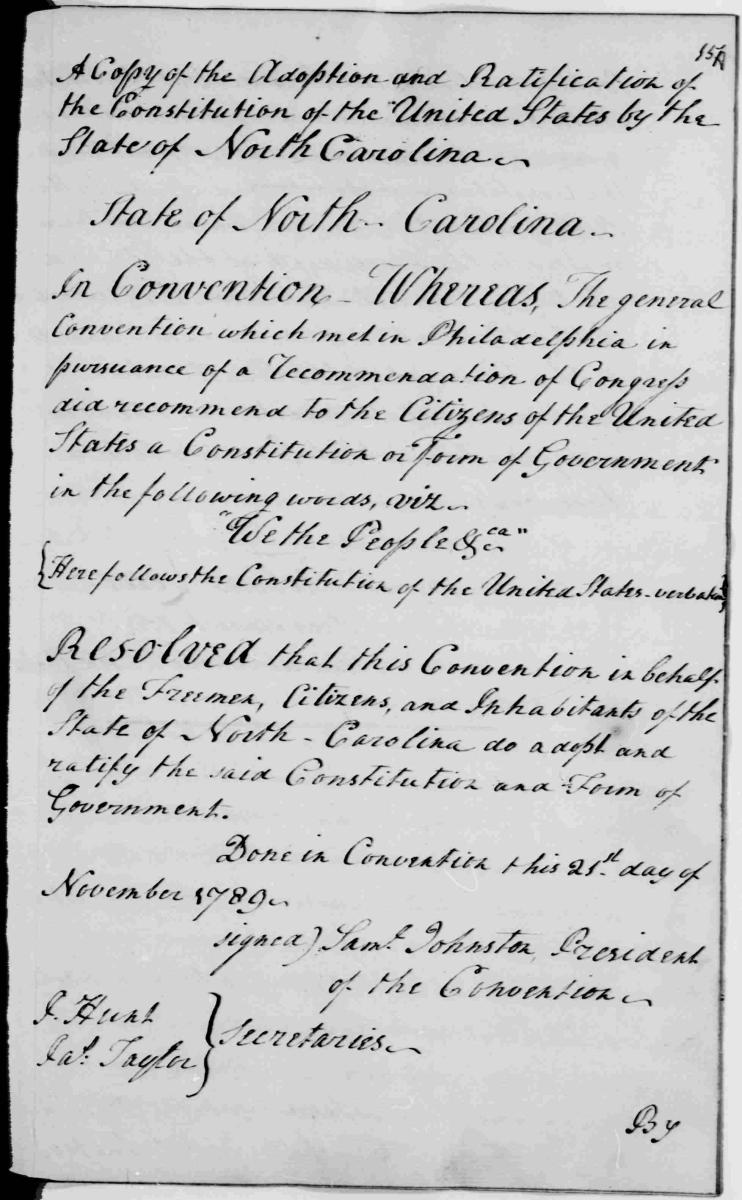

On 21 November, after five days of deliberations, William R. Davie finally put the ratification question before the convention. Supporters predictably overwhelmed opponents by a margin of 194 to 77. John Huske of Wilmington then led a previously planned walkout of about 68 Anti-Federalists from the chamber in a last defiant gesture. The convention adjourned on 23 November, having made North Carolina the twelfth state to embrace the United States and its Constitution.

References:

John C. Cavanagh, Decision at Fayetteville. The North Carolina Ratification Convention and General Assembly of 1789 (1989).

Alan D. Watson, "North Carolina: States' Rights and Agrarianism Ascendant," in Patrick T. Conley and John P. Kaminski, eds., The Constitution and the States: The Role of the Original Thirteen in the Framing and Adoption of the Federal Constitution (1988).

Additional Resources:

Howard, Thomas L. “The State That Said No: The Fight for Ratification of the Federal Constitution in North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review 94, no. 1 (2017): 1–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45184801.

1 January 2006 | Cavanagh, John C.