Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC)

"Work and Opportunity: African Americans in the CCC"

by Dr. Olen Cole Jr.

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2010.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

One of the most popular programs in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal proved to be the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The program’s goal was to conserve the country’s natural resources while providing jobs for young men. African American men played a major role in the CCC in North Carolina. These men built truck trails and roads in the Nantahala National Forest, helping to provide easy access to the Great Smoky Mountains. They constructed telephone lines. They removed dead trees to prevent forest fires. Workers put out forest fires, too, saving timber, property, and possibly even lives. They lessened soil erosion by laying topsoil to prevent land- and mudslides, by landscaping, and by planting trees and shrubs. This work benefited forestland and agricultural areas across North Carolina.

Although most Americans experienced economic hardship during the Depression, some groups and populations suffered more than others. Because of competition for jobs, those without experience or a specific skill found it very difficult to find work. Young people struggled a great deal. The widespread racism and segregation of the time made the suffering of African American youth even worse.

President Roosevelt responded to the Depression in March 1933 by convincing Congress to create the CCC. In 1933 over a third of the 14 million known unemployed were under age 25. The CCC provided conservation jobs for unemployed men, ages 18 to 25, in semimilitary work camps, usually in rural areas. (Some people called the CCC “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” because its focus included the planting of millions of trees.)

The enrollee (the official term for a CCC participant) was to be employed in the corps for no longer than 18 months. His family had to be receiving some form of government financial assistance. Each enrollee earned a monthly salary of $30 (a fairly good salary for the 1930s), of which $25 was sent home to his family to help buy food, clothing, and fuel. The enrollee kept the remaining $5 to use as he chose. Enrollees received food, clothing, shelter, medical care, and educational and recreational opportunities. They lived in barracks (usually wooden cabins) and got two standard CCC uniforms.

The law establishing the CCC contained a provision that “no discrimination shall be made on account of race, color or creed.” Oscar De Priest, a black congressman from Chicago, insisted on this measure. Yet despite instructions from National Selection Director W. Frank Persons that enrollees be selected without regard to race, CCC administrators in many states refused to select a proportionate share of blacks. By 1935, African American participation in the CCC did reach 10 percent, which might be considered equitable in relationship to the black population in 1930. But, as one historian has written, it was “less than adequate when measured against the disproportionate relief needs of blacks.”

CCC Camps and Work Projects

At first, African American enrollees were to be assigned to CCC camps without regard to race. This did not always happen. Controversies over enrollment of African Americans in the CCC, the location of camps housing them, and the jobs they were assigned lasted throughout the program’s existence. Because of hostility and harassment from some communities, officials separated black and white enrollees. In the South, racially segregated camps were the norm from the beginning.

Between 1933 and 1942, at least 11 African American CCC companies worked in the state of North Carolina. Letters in names identified the racial makeup of the camps. For instance, the “C” in Company 410-C identified the camp as “colored,” a common term at the time. Company 411-W was “white.” North Carolina companies usually averaged between 150 and 200 men.

Most CCC companies in the state performed a variety of tasks, with the camps best described as multipurpose facilities. Officials assigned some companies, however, to “special work projects.” Each camp had two to six project superintendents. Each superintendent had a crew assigned to a particular task: fire suppression or installation of telephone lines, for example. Specific work projects usually lasted for three weeks, at the most. Some African American companies worked on special projects. In an area of Forest City, in Rutherford County, for example, Company 5423-C workers gullied and fenced over 3,000 acres. They planted hundreds of trees and shrubs to reshape the land and stabilize the erosion. This project resulted from a cooperative agreement between the Department of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service and private landowners.

Company 3444-C—perhaps the most mysterious African American company that worked in the Tar Heel State, with little information recorded about it—was assigned to Camp Buck Creek in Macon County, about 21 miles west of Franklin, in the Nantahala National Forest. It later moved to Rainbow Springs. (Company 3444-C had been organized at Fort McPherson, Georgia, but soon ordered to North Carolina. Community resistance to its placement may have been the reason.) Initial work projects in the forest around Franklin included construction of truck trails, roads, and telephone lines, and prevention and suppression of forest fires. In addition to contributing to the development of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the company worked on construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Four CCC camps were established along the parkway route.

Company 3444-C—perhaps the most mysterious African American company that worked in the Tar Heel State, with little information recorded about it—was assigned to Camp Buck Creek in Macon County, about 21 miles west of Franklin, in the Nantahala National Forest. It later moved to Rainbow Springs. (Company 3444-C had been organized at Fort McPherson, Georgia, but soon ordered to North Carolina. Community resistance to its placement may have been the reason.) Initial work projects in the forest around Franklin included construction of truck trails, roads, and telephone lines, and prevention and suppression of forest fires. In addition to contributing to the development of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the company worked on construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Four CCC camps were established along the parkway route.

Former Enrollee Recollections of the CCC

A paycheck was not the only good thing about being in the CCC. In written surveys and oral interviews done between 1989 and 1995, African Americans who served in the program in North Carolina said that they mainly benefited in three areas: employment, training, and character development.

The CCC emphasized providing jobs for needy youth, and that was the main reason for joining. One former enrollee who had been an orderly and assistant pay clerk for Company 5424-C remarked, “There were no jobs of a regular nature. Also, it was a chance to send my mother $25 each month.” A former camp blacksmith said, “Times were tight and I needed money at the time.” Declared a former kitchen worker at a New Bern camp, “Times were very tough. My father was not making enough money to make ends meet so I joined the three C’s to help the family.” A former assistant squad leader from Warsaw agreed: “There were not jobs in these small towns, so I joined the CCC.”

Although many CCC projects required only the simplest types of common labor, enrollees could learn other things. Indeed, most of the CCC veterans interviewed admitted that they learned about cooperation with fellow workers and supervisors, the proper care of equipment, the importance of hard work, and a responsible attitude toward a job. While most respondents indicated that their CCC duties did not prepare them for future employment in terms of specific skills, some said that the work did prepare them for their lifetime careers. One former surveyor and topographic mapper with Company 5420-C commented: “My work in the CCC was really the launching pad for my career with the North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service.” One retired CCC worker recalled, “Because I had operated a machine in the CCC, the navy shipyard in Philadelphia was eager to hire me.” He also noted that his experience as a truck operator while in the CCC led to his assignment as a vehicle operator in the United States Army during World War II.

Although many CCC projects required only the simplest types of common labor, enrollees could learn other things. Indeed, most of the CCC veterans interviewed admitted that they learned about cooperation with fellow workers and supervisors, the proper care of equipment, the importance of hard work, and a responsible attitude toward a job. While most respondents indicated that their CCC duties did not prepare them for future employment in terms of specific skills, some said that the work did prepare them for their lifetime careers. One former surveyor and topographic mapper with Company 5420-C commented: “My work in the CCC was really the launching pad for my career with the North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service.” One retired CCC worker recalled, “Because I had operated a machine in the CCC, the navy shipyard in Philadelphia was eager to hire me.” He also noted that his experience as a truck operator while in the CCC led to his assignment as a vehicle operator in the United States Army during World War II.

The CCC also provided an education program, conducted during off-duty hours on a voluntary basis. The goal was to help enrollees improve themselves and become more employable once of some academic courses. One respondent from Wilson said, “I improved my reading, arithmetic, spelling, and writing.” A former supply steward from Mars Hill commented that the lessons in reading and spelling greatly helped. Another recalled that, “I [had] only completed the sixth grade, so I participated in some reading and writing classes.”

The CCC educational program gave some of the respondents a chance to complete high school. It motivated others to continue with college work. One CCC veteran who had not completed high school before joining the corps said that his participation in the educational program at Camp Carr gave him an incentive to complete his General Education Diploma (GED) when he entered the army in 1942: “After taking courses in the three C’s I wanted to finish high school after joining the service.” One veteran of the CCC’s Camp Patterson declared, “After I got my [CCC] discharge in 1938, I continued to take courses until I graduated from college in 1942.” A 1948 graduate of what is now North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro recalled his classes at the State Forest camp near Maple Hill: “The education program was the most important experience. I got a leave from the CCC to go to A&T.” Another enrollee in Maple Hill who participated in the camp education program said, “Following my CCC experience I joined the navy. After World War II, I attended and graduated from Delaware State.”

Overall, although former enrollees had mixed opinions about the job training they got in the CCC, most considered their work experience to be valuable. The CCC provided direct and immediate financial benefits, and participation enhanced future work habits.

Overall, although former enrollees had mixed opinions about the job training they got in the CCC, most considered their work experience to be valuable. The CCC provided direct and immediate financial benefits, and participation enhanced future work habits.

Although the CCC program ended in 1942, its impact continued. Unquestionably, enrollees made important contributions to the maintenance of North Carolina’s natural resources. They planted millions of trees; built hundreds of lookout towers; built thousands of miles of telephone lines, truck trails, and minor roads; and saved thousands of acres of land from the ravages of disease, fire, and soil erosion. The CCC built or improved many parks and recreation areas, including Fort Macon State Park, Hanging Rock State Park, Cape Hatteras State Park, Mount Mitchell State Park, and Morrow Mountain State Park, as well as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway. African American corpsmen participated fully in this conservation of the state’s natural resources, gaining valuable education and work skills along the way.

*At the time of this article’s publication, Dr. Olen Cole Jr. was a professor in and chairperson of the Department of History at North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro. He wrote The African American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps (Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 1999).

References and Additional Resources

African Americans in the Civilian Conservation Corps. New Deal Network. http://newdeal.feri.org/aaccc/index.htm

The Civilian Conservation Corps. From PBS' American Experience Series. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/ccc/

Interactive periodic table of the New Deal. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Hyde Park, NY, USA. http://lxfdrweb.it.marist.edu/education/resources/periodictable.html

Paige, John C. 1985. The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An administrative history. National Park Service. http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/ccc/index.htm

Resources on the Civilian Conservation Corps in libraries [via WorldCat]

Williams, Gerald W. The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Forests. FSToday. http://www.fs.fed.us/gpnf/research/heritage/LookingBackTheCivilianConservationCorpsandTheNationalForests.htm

Works Projects in North Carolina, 1933-1941. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, USA. http://exhibits.archives.ncdcr.gov/wpa/

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Enrollee Records, Archival Holdings and Access, National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/st-louis/archival-programs/civilian-personnel-a...

Image Credits:

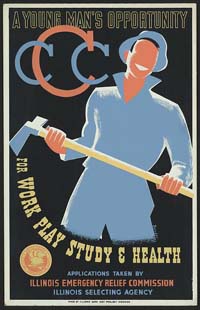

Bender, Albert M. 1941. A young man's opportunity for work, play, study & health. Reproduction # LC-DIG-ppmsca-12896. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC, USA. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92513367/

CCC application for Arlie Dodge. Civilian Conservation Corps Collection, Colorado State Archives. http://www.colorado.gov/dpa/doit/archives/ccc/cccscope.html

Civilian Conservation Corps, Kane, Pennsylvania, Co. 2314-C: radio code practice, 1933. The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Available from the ExplorePAHistory website. http://explorepahistory.com/displayimage.php?imgId=5266

Enrollee sighting through an engineer’s level at camp SCS-NC-5, Yanceyville, North Carolina. Item 35G, No 263, National Archives, College Park, MD, USA. Available from the US Department of Agriculture, National Resources Conservation Service website. http://www.la.nrcs.usda.gov/partnerships/ccc.html

View of large trail shelter built for the United States Forest Service by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1938 on Craggy Knob. Facing northwest. c.1996.

Item #HAER NC,11-ASHV.V,2-170. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Available in this set: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/NC0478/

1 January 2010 | Cole, Olen