Stonewall Jackson Manual Training

In late nineteenth-century North Carolina, young men convicted of criminal offenses were subjected to the same harsh sentences and punishments as hardened adult criminals. In 1890 James P. Cook, a resident of Concord and editor of the local daily newspaper, the Standard, witnessed a sentence of "three years and six months at hard labor on the Cabarrus County Chain Gang" imposed on a 13-year-old boy convicted of petty theft. Distressed at the sight of the lad taken from the courtroom chained to a convicted adult criminal, Cook devoted the next 17 years to a campaign for the establishment of a training school for boys.

Supporters of such a school, particularly the benevolent organization King's Daughters of North Carolina, finally convinced the state legislature to embrace their "radical" idea. A special committee of the King's Daughters in 1906 successfully campaigned for the school through public meetings, newspaper articles and editorials, and the dissemination of pamphlets describing the success of reformatories in other states. Success in the legislature was finally assured when sponsors of the bill gained the support of the Confederate veterans in the General Assembly, proposing that the new institution be named in honor of beloved Confederate general Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, who died during the Battle of Chancellorsville. The act establishing the Stonewall Jackson Manual Training and Industrial School in Concord became law on 2 March 1907.

Governor R. B. Glenn named James P. Cook to the school's first board of trustees. The board then elected Cook as its chairman, a position he held for almost two decades. At a public meeting in Concord on 30 Sept. 1907, the citizens of Cabarrus County appointed a committee to raise funds and locate land to be donated to the training school trustees to secure placement of the new school within Cabarrus County. The fund-raising effort was successful, and the school was located on a site that is now within the Concord city limits. In November 1907, the executive committee of the trustees named Professor Walter Thompson, then superintendent of Concord public schools, the first superintendent of instruction at Stonewall Jackson Training School.

From the beginning, school officials insisted that a quality education be offered to the young people committed to their care. The school was proud of its staff of certified teachers, its library, and its visual aids and resource materials. In addition to more traditional academic instruction, young men received training in a useful trade. Students worked in the shoe shop, machine shop, sewing room, print shop, barber shop, textile plant, and on the school's farm or in its dairy barn. For many years, students in the print shop published a magazine, called the UPLIFT, under the supervision of printing instructor Jesse C. Fisher. Young men learned modern farming techniques raising their food in school fields. Others helped tend the herd of dairy cows that furnished milk and ice cream for the school. "Big Buck," a prize-winning bull, presided over a large herd of Hertford beef cattle that furnished meat for the school kitchen.

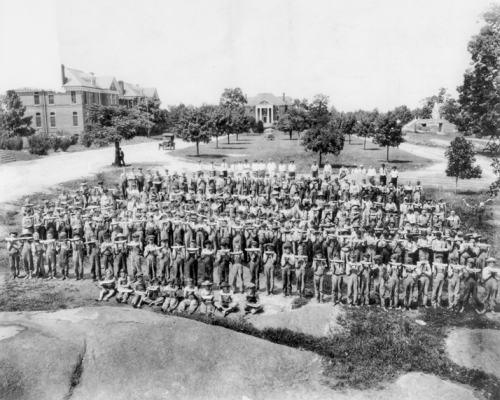

Legislative policy eventually shifted away from the incarceration of juvenile offenders found guilty of "status" offenses such as truancy and undisciplined behavior. As a result, the Stonewall Jackson population had dwindled by the early 2000s to an average of 150 young men, from a peak population of 500 juveniles at the school's zenith. The crimes committed by juveniles confined at the school tend to be much more violent than 20 years ago; many are drug- and weapons-related offenses. Consequently, a fence has been installed to prevent students from leaving the grounds.

Reference:

Samuel G. Hawfield, History of Stonewall Jackson Manual Training and Industrial School (1946). https://archive.org/details/historyofstonewa00hawf/page/119

Additional Resources:

"Stonewall Jackson Training School." N.C. Highway Historical Marker L-49, N.C. Office of Archives & History. http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-49

"Youth Development Centers." N.C. Department of Public Safety. https://www.ncdps.gov/juvenile-justice/juvenile-facility-operations/youth-development-centers (accessed November 12, 2019).

Leland,Elizabeth. "Stonewall Jackson secrets: ‘Children against monsters’." The Charlotte Observer. October 5, 2013.

1 January 2006 | Horton, Clarence E., Jr.