Caswell, Richard

3 Aug. 1729–10 Nov. 1789

See also: Richard Caswell, Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History

Richard Caswell, militia officer and governor of North Carolina, was born at Joppa, then a flourishing seaport and the county seat of Baltimore County, Md. His parents were Richard Caswell and Christian Dallam. Their plantation home, Mulberry Point, stood on a promontory north of the town, overlooking the Chesapeake Bay. He received his early education at the parish school taught by the Reverend William Cawthorn and the Reverend Joseph Hooper at St. John's (Anglican) Church in Joppa.

Richard Caswell, militia officer and governor of North Carolina, was born at Joppa, then a flourishing seaport and the county seat of Baltimore County, Md. His parents were Richard Caswell and Christian Dallam. Their plantation home, Mulberry Point, stood on a promontory north of the town, overlooking the Chesapeake Bay. He received his early education at the parish school taught by the Reverend William Cawthorn and the Reverend Joseph Hooper at St. John's (Anglican) Church in Joppa.

The elder Richard Caswell married late in life and had eleven children. By 1743 his health failed and, despite their youth, the two oldest sons, William and Richard, had to assume the major responsibilities of conducting their father's mercantile business and farming operations. This turn of events introduced Richard to business management and finance. However, the family fortunes went from bad to worse during Joppa's decline as a seaport, and in 1745 the family decided to follow family friends to North Carolina.

Baltimore County records show that the elder Richard Caswell sold his real estate at Joppa in 1745 to his brother-in-law, William Dallam. His health prevented early departure, however. It was finally decided that William and Richard, Jr., would go on to North Carolina to seek employment, obtain land if possible, and prepare a place to which the rest of the family could come.

Richard and William reached New Bern in late autumn of 1745 with a letter of recommendation from the governor of Maryland to North Carolina's royal governor, Gabriel Johnston. William was given employment in the secretary's office. Richard, then age sixteen, was made an apprentice to the surveyor general, James Mackilwean. For the next two years he lived with the Mackilwean family on their 850-acre plantation, Tower Hill, located at Stringer's Ferry on Neuse River, near present Kinston. During the rest of his life, Richard Caswell resided in that vicinity. By 1747 his training was completed, and he became deputy surveyor general upon reaching age eighteen. Also in 1747 he got his first land grant and built on it the home for his parents and their children. This home, then called The Hill, was renamed Newington-on-the-Hill by Caswell in February 1776; in about 1840 it was renamed Vernon Hall by a later owner, John Cobb Washington. After 1912 the house was rebuilt or greatly altered, but the present Vernon Hall and about six acres of ruined gardens and grounds still occupy the site. It was annexed to Kinston in the twentieth century.

While living with the Mackilwean family, Richard was introduced to North Carolina politics. James Mackilwean, besides being surveyor general, was long a member of the General Assembly, as was a neighbor, Dr. Francis Stringer. In his spare time, Caswell assisted Stringer in his business enterprises at Stringer's Ferry. The political interests and activities of Mackilwean and Stringer were educational for Caswell and offered him opportunities to become acquainted with other political leaders. When Johnston County was formed from upper Craven in 1746, the county seat was for several months at Stringer's Ferry. Richard's brother, William, and his father served as deputy clerk and clerk of the Johnston County court. Richard became an officer in the troop of horse of the Johnston County militia, and from 1749 to 1753 he also gained experience as deputy clerk. In 1753 he served a few weeks as the first clerk of Orange County court, when that county was formed from upper Johnston; he resigned upon being appointed high sheriff of Johnston.

On 21 Apr. 1752, Richard Caswell was married at Tower Hill to Mary Mackilwean (b. 1731), the daughter of James and Elinor Mackilwean. To this marriage three children were born. One daughter died at birth (15 Sept. 1753). A son, William (b. 24 Sept. 1754), grew to manhood and attained distinction during the Revolution. Another daughter (b. 4 Feb. 1757) apparently died in infancy. Mary Caswell died on 7 Feb. 1757, from complications of childbirth. During the marriage, the family lived at the Red House, a plantation home at the site of the present Richard Caswell Memorial Park in western Kinston. According to Caswell's will, his first wife and her son, Brigadier General William, are buried in the cemetery at the Red House plantation; their graves are unmarked, however.

On 21 Apr. 1752, Richard Caswell was married at Tower Hill to Mary Mackilwean (b. 1731), the daughter of James and Elinor Mackilwean. To this marriage three children were born. One daughter died at birth (15 Sept. 1753). A son, William (b. 24 Sept. 1754), grew to manhood and attained distinction during the Revolution. Another daughter (b. 4 Feb. 1757) apparently died in infancy. Mary Caswell died on 7 Feb. 1757, from complications of childbirth. During the marriage, the family lived at the Red House, a plantation home at the site of the present Richard Caswell Memorial Park in western Kinston. According to Caswell's will, his first wife and her son, Brigadier General William, are buried in the cemetery at the Red House plantation; their graves are unmarked, however.

On 20 June 1758, Caswell married Sarah Heritage (1740–94), a daughter of William Heritage and his first wife, Susannah Moore. To this marriage eight children were born: Richard, Jr. ("Dicky"; b. 15 Sept. 1759); Sarah (b. 26 Feb. 1762); Winston (b. 7 May 1764); Anna (b. 4 Dec. 1766); Dallam (b. 15 June 1769); John ("Jack"; b. 24 Jan. 1772); Susannah ("Susan"; b. 16 Feb. 1775); and Christian (7–9 Jan. 1779). Eight of the eleven children lived to adulthood.

Caswell's second father-in-law, William Heritage (ca. 1700–1769), also had a great influence upon Caswell's career. Heritage was a lawyer, planter, and political leader. From 1738 until his death in 1769, he served as clerk of the General Assembly, an influential post in the colonial government. He was a native of Bruton Parish, York County, Va., and had an excellent education. Caswell studied law under Heritage from 1758 to 1759 and was admitted to the bar on 1 Apr. 1759. At the same time he was commissioned deputy attorney general; he served in that post about four years.

From 1754 to 1776, Caswell was a member of the colonial assembly. In the period 1770–71 he was speaker of the house. As a legislative leader, he played a key role in the development and enactment of legislation relating to trade and industry, the court system, public defense, and humanitarian concerns. Most remarkable was his proposal for "erecting and establishing a free-school for every county," using as initial funding several thousand pounds granted to the province as reimbursement for aid rendered the Crown in the French and Indian War. The resulting "Address of the General Assembly," sent to the king in 1760, was cited to legislatures for many decades thereafter on behalf of free public schools. Caswell wrote the concept into the state's first constitution, as chairman of the drafting committee of the provincial congress of December 1776 that drew up the document.

The period from 1765 to 1775 was for North Carolina a decade of developing anti-British sentiment, protest activities, and public demonstrations. During this period, Caswell's private views were held in closest confidence, and to this day they are not certainly known. His public actions were ambivalent. Royal governors continued to trust him until April 1775; yet he held throughout the same period the highest confidence of the populace and their leaders in the assembly. In 1769 he was a leader in the "convention" into which the General Assembly at New Bern resolved itself immediately following Governor William Tryon's edict dissolving the assembly to prevent its resolving upon a public boycott of British goods. The congress defiantly adopted the boycott resolutions. Caswell was elected speaker of the next assembly, which expelled Harmon Husband, representative from Orange County and fiery advocate of the reforms demanded by thousands of back country Regulators. Governor Tryon immediately had Husband arrested, jailed, and charged with libel and sedition. Caswell was foreman of a grand jury that twice refused to indict Husband. Nevertheless, when the Regulators threatened to march on New Bern, rescue Husband, and lay the town in ashes, Caswell, as colonel of the Dobbs militia, supported the royal governor's decision to fortify New Bern and organize an army to march against the Regulators. Caswell commanded the right wing of Tryon's army, which defeated a poorly equipped army of about 3,400 Regulators on 16 May 1771, at the Battle of Alamance.

A few months later, Caswell was appointed by the new royal governor, Josiah Martin, as one of three judges of the court of oyer and terminer and general gaol delivery. He was not reelected speaker by the next assembly, but on 8 Dec. 1773 he was appointed by Speaker John Harvey to serve with eight others as a standing committee of correspondence and inquiry. This committee supported cooperation of all the colonies in resisting the five Intolerable Acts of Parliament. Three of its members later served as state governor, two signed the Declaration of Independence, and three served as Revolutionary War generals. Caswell was a leader in all five of North Carolina's provincial congresses and also served in the First and Second Continental Congresses.

Royal Governor Josiah Martin reported that Caswell, after his return from the Second Continental Congress, became "the most active tool of sedition," a statement well justified by the facts. Caswell had conceived a daring plan to put all governmental powers at the disposal of the provincial congress. Alarmed by rumors of plans to take the governor and council prisoners, Martin fled the palace, calling upon the council members to join him aboard the British warship Cruzier. Caswell "had the insolence to reprehend the Committee of Safety for suffering me to remove from thence," Martin indicated later. The first step in Caswell's plan was thus frustrated, but not entirely: he prevailed upon council Secretary Samuel Strudwick to defect with the public records and hold them at the disposal of the provincial congress.

When the provincial congress met on 20 Aug. 1775, Caswell quietly arranged a further step: the seizure of the provincial treasury in order to deprive the royal government of tax support and to place all public revenues at the disposal of the provincial congress. This the congress did on 8 Sept. 1775, by electing its own treasurers of the province's two treasury districts. Caswell and Samuel Johnston were elected and bonded to receive all taxes and to emit bills of credit by authority of the provincial congress. Caswell immediately resigned as a delegate to the Continental Congress and accepted this more dangerous assignment. The plan was completed in the same provincial congress by providing for the military defense of its authority. It ordered under arms six battalions of five hundred minutemen each, and two additional battalions were ordered for a proposed Continental Army. Caswell was appointed commander of the minutemen for the New Bern District. Six months later he led this brigade to victory at the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge on 27 Feb. 1776, against a force of Scottish Loyalists marching to Wilmington to unite with a royal fleet and army expected on the coast.

Caswell was elected governor of the state by the provincial congress in December 1776 and was reelected to annual terms under the constitution by the General Assemblies of 1777, 1778, and 1779. The constitution allowed only three successive terms. As governor he was incessantly raising and equipping troops. Besides providing for its own defense, the state sent more than eighteen thousand officers and men including Continentals to the aid of other states. Caswell was in poor health when he left office in April 1780, but he was immediately elected a major general by the General Assembly, placed in command of the state militia, and empowered to appoint staff officers.

Despite ill health, Caswell commanded the North Carolina Militia under General Horatio Gates at the disastrous Battle of Camden on 16 Aug. 1780, sharing the shame of the defeat. After taking steps to reorganize and to strengthen the militia for defensive actions in the west, he reported to the General Assembly at Hillsborough. The assembly took consideration of Caswell's illness and on 12 Sept. relieved him temporarily from command of the state militia, leaving him in the separate command of the North Carolina Partisan Rangers, guerrilla forces first established by Caswell in 1776 and kept under his command throughout the war. The militia was returned to his command a few weeks later.

From May 1782 until May 1785, Caswell served as state controller general and made headway in bringing order to the public accounts. In 1785 he was again elected governor and, by successive elections, served until 1787. When not serving in the governor's office, he had always been elected to represent Dobbs County in the General Assembly. His vigorous support of the proposed federal Constitution alienated his Dobbs constituency, however, and it denied him a seat in the constitutional convention held at Hillsborough in 1788. He was, however, reelected to the legislature. Caswell was also a Mason, and served as Grandmaster for the state of North Carolina from November 1788 until he died.

The period from 1784 to 1789 was one of grief for Caswell. His two oldest sons, his oldest daughter, his mother, two brothers, and a sister all died. His throbbing headaches and giddiness came more often and stayed longer. These symptoms, of which he had complained at times since 1769, were evidently caused by high blood pressure. On 8 Nov. 1789, he suffered a fatal stroke of total paralysis while presiding over the state senate at Fayetteville. A state funeral was held at Fayetteville. His body was then taken to Kinston and buried in the cemetery at the Red House plantation. His widow, Sarah Heritage Caswell, died at Newington in 1794.

This person enslaved and owned other people. Many Black and African people, their descendants, and some others were enslaved in the United States until the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in 1865. It was common for wealthy landowners, entrepreneurs, politicians, institutions, and others to enslave people and use enslaved labor during this period. To read more about the enslavement and transportation of African people to North Carolina, visit https://aahc.nc.gov/programs/africa-carolina-0. To read more about slavery and its history in North Carolina, visit https://www.ncpedia.org/slavery. - Government and Heritage Library, 2023

References:

Alexander, Clayton B. "The Public Career of Richard Caswell." Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, 1930.

Ashe, Samuel A. Biographical History of North Carolina, vol. 3. 1905.

Connor, R. D. W. Revolutionary Leaders of North Carolina. 1916.

Martin, Francois X. A Funeral Oration of the Most Worshipful and Honorable Major-General Richard Caswell. 1791.

Newbern Gazette. December 15, 1798.

Saunders William L., Walter Clark, eds. Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Vol 8–22. 1890–1907.

University of North Carolina Magazine, No. 4. March 1855.

University of North Carolina Magazine, No. 7. Aug. 1857.

University of North Carolina Magazine, No. 7 Nov. 1857.

Additional Resources:

"Richard Caswell." N.C. Highway Historical Marker F-2, N.C. Office of Archives & History. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=F-2 (accessed February 22, 2013).

Richard Caswell Family Bible Records. 1712-1788. North Carolina Digital Collections. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/richard-caswell-family-bible-records/1391047 (accessed February 21, 2013).

"CSS Neuse & Gov. Caswell Memorial: ." N.C. Historic Sites, N.C. Office of Archives & History: http://www.nchistoricsites.org/neuse/caswell.htm (accessed February 22, 2013).

North Carolina Digital Publishing Office. “The Gourd Patch Conspiracy.” MosaicNC.org. July 2023. https://mosaicnc.org/Gourd-Patch (accessed September 23, 2023).

Richard Caswell Papers, 1776-1914 (bulk 1776-1785) (collection no. 00145-z). The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/c/Caswell,Richard.html (accessed February 22, 2013).

Richard Caswell Collection, 1930-2007 (Manuscript Collection #1117). East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina. http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/special/ead/findingaids/1117/ (accessed February 22, 2013).

Richard Caswell Papers, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, USA. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/collections/governors-papers-historical?filter_7=Caswell%2C%20Richard%2C%201729-1789.&applyState=true

"Caswell, Richard, (1729 - 1789)." Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=C000246 (accessed February 22, 2013).

Haywood, Marshall De Lancey. 1906. The Beginnings of Freemasonry in North Carolina and Tennessee. Raleigh: Weaver & Lynch. https://archive.org/details/The_Beginnings_Of_Freemasonry_In_North_Carolina_And_Tennessee_1906_-_Haywood

"Trends in the runaway slave advertisements." North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices, 1750-1865. Digital Library on American Slavery. Accessed March 29, 2023 at https://dlas.uncg.edu/notices/trends/.

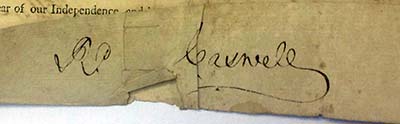

Image Credits:

"Thought to be Richard Caswell." Photograph no. 71.10.87. From the Audio Visual and Iconographics Collection, Division of Archives and History Photograph Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, N.C.

1 January 1979 | Holloman, Charles R.