WWI: Boot camp in Charlotte

In the summer of 1917, the United States government needed places to train large numbers of troops quickly. It looked to the South because of its warm climate. The North Carolina cities of Fayetteville and Charlotte sent delegations to Washington, D.C., and competed for the favor of officials in charge of locating the new camps. On July 13, the officials announced Charlotte as their choice for Camp Greene. Fayetteville citizens immediately asked Charlotte officials to help them obtain a camp, too. Later Fayetteville and Raleigh both became sites for army camps. Before the war was over, other camps were also built: Camp Bragg in Fayetteville and Camp Polk in Raleigh.

In the summer of 1917, the United States government needed places to train large numbers of troops quickly. It looked to the South because of its warm climate. The North Carolina cities of Fayetteville and Charlotte sent delegations to Washington, D.C., and competed for the favor of officials in charge of locating the new camps. On July 13, the officials announced Charlotte as their choice for Camp Greene. Fayetteville citizens immediately asked Charlotte officials to help them obtain a camp, too. Later Fayetteville and Raleigh both became sites for army camps. Before the war was over, other camps were also built: Camp Bragg in Fayetteville and Camp Polk in Raleigh.

No time was wasted after the decision to build Camp Greene. On July 23, the Consolidated Engineering Company of Baltimore, Maryland, put 1,200 men to work on the project. Eventually, there would be nearly 8,000 men working to build the camp.

Camp Greene was named in honor of Revolutionary War General Nathanael Greene. It occupied 2,500 acres and had 2,000 buildings, including a 60-acre hospital facility with 2,000 beds. It had more than a mile of horse stables, a YMCA, a post office, and a bakery that produced 40,000 loaves of bread a day. The camp had 25 miles of roads, 50 miles of water pipe, and 301 miles of electrical wire. An additional 15,000 acres west of Charlotte were used for rifle and artillery ranges. The lumber it took to build Camp Greene could have paved a walkway two feet wide from Charlotte to the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

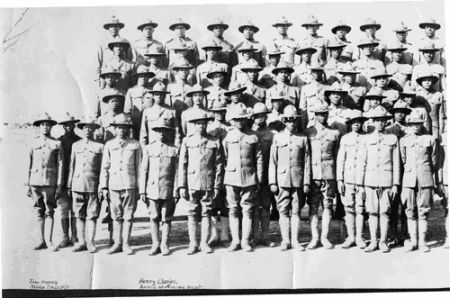

The first troops arrived on September 6, only six weeks after construction of the camp had begun. Most of the men who were sent to Camp Greene came from New England and the western states. Troops from Massachusetts accounted for the largest number. The camp was a melting pot of nationalities, and some of the troops were recent immigrants who barely spoke English. About five hundred men took English lessons at the YMCA. Few people had expected any black troops to be sent to a southern camp, but at one time 14,000 black troops from Massachusetts and Connecticut were stationed there. In all, Camp Greene added 40,000 people to the Charlotte area.

Men expecting to enjoy the sunny South soon found themselves facing one of the harshest winters on record. Heavy rain, snow, sleet, and extreme cold plagued the camp, which stayed muddy for most of its existence. Troops living in tents on wooden platforms had difficulties staying warm. Most were forced to burn green wood for fuel, which gave off a lot of smoke but little heat.

Troops remained at the camp for thirty to ninety days while they trained in trench warfare. More than five miles of zigzag trenches were dug to duplicate the ones on battlefields in France. These trenches averaged a depth of eight feet, but some were fifteen feet deep, and some had bunkers as deep as thirty feet underground.

The day started at 5:45 A.M. when the bugler blew reveille, and ended at 11:00 P.M. with taps. Weekends provided time for recreation including baseball, football, boxing, and volleyball.

There were remarkably few disciplinary problems, considering the tens of thousands of men who passed through Camp Greene. Records indicate only 2,200 charges for minor offenses and just 500 courts-martial.

The most serious problem the camp faced was the influenza epidemic of 1918 and 1919. It is estimated that half of the 80,000 people who lived in Charlotte and at Camp Greene were infected, causing more than 1,200 deaths in a few short months. One funeral home had sixty bodies awaiting burial, and citizens told of coffins stacked like wood at the train station, waiting to be shipped home.

During World War I, the United States government established the Fosdick Commission to aid relations between army camps and nearby civilian populations. In Charlotte, commission members made sure that soldiers had rooms in the city and found space for visiting families. Townsfolk provided socials, band concerts, and community sings. Churches organized to make everyone feel at home. Some Sundays as many as 4,000 soldiers were invited to individual homes for dinner after church services. Businesses were monitored to prevent price gouging, and the sale of liquor was carefully controlled.

Camp Greene, Camp Bragg, and Camp Polk aided the war effort by training troops. But they also greatly helped the economic development of North Carolina. Camp Greene brought thousands of men to this state, and many returned to marry and settle down when the war ended. Charlotte's growth as a major city started with the decision to build Camp Greene.

At the time of this article’s publication, Edward S. Perzel taught North Carolina history and was associate dean in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. He was active in historic preservation and local history research in Charlotte.

Additional resources:

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI. NC Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm

"World War I." North Carolina Digital History. Learn NC. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newcentury/3.0

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit, State Archives of NC. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm

Image credits:

"Unknown African-American Company A." Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Public Library of Charlotte Mecklenburg County. Image# PLCMC-0040.

1 May 1993 | Perzel, Edward S.