WWI: Support from the home front

When most people hear the word war they think of soldiers and sailors, guns and battles, death and destruction. Those are all part of war, but historians also study everything and everyone affected by conflicts. This is especially true of what military historians call total war.

When most people hear the word war they think of soldiers and sailors, guns and battles, death and destruction. Those are all part of war, but historians also study everything and everyone affected by conflicts. This is especially true of what military historians call total war.

In many ways, World War I was a total war for the people of North Carolina. Even before the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, 90 percent of the people favored building up the country’s armed forces. When America entered the conflict, there was a great outburst of patriotism. One Wadesboro paper reported that “there is a great deal of interest being shown here in the impending war, and the President and Congress have the support of the entire community.” A mass meeting in Troy pledged loyalty and support. On the Sunday after war was declared, almost all the ministers in Raleigh preached patriotic sermons. At Tabernacle Baptist Church, which was draped in flags, the minister said in his sermon that it was “the call of God to fight for human liberty and for Him.”

In response to the rise in patriotism, many Americans volunteered for military service. Their numbers, however, were too small to build the large army needed to fight the war. On June 5, 1917, President Wilson called on all males ages twenty-one to thirty-one to register for the draft. More North Carolina men in that age group rushed in to register than were thought to live in the state. Over a thousand men refused to sign up and went into hiding, but they were a minority. By the end of the war, 337,986 whites and 142,505 blacks were registered in North Carolina. Of that number, 40,740 whites and 20,082 blacks were called to serve in the armed forces.

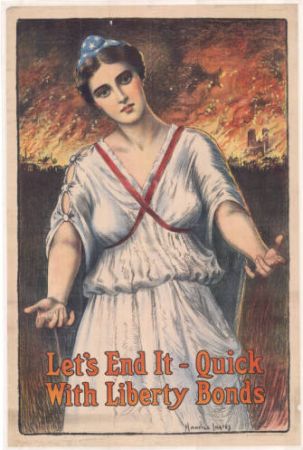

At home, buying war bonds or savings stamps was probably the most common way to support the war. When people bought a bond or a savings stamp, they were lending money to the government. Their money would be paid back with interest after the war. Organizations in each county worked to contact every citizen during four Liberty Loan drives. In Kinston the money raisers called themselves the Liberty Loan Navy because they had to ford creeks, wade through mud, and face drenching rain. Meetings and rallies were held everywhere. At a meeting in Asheville, the local congressmen spoke, followed by a French army officer who sang the French national anthem. He reminded his audience how France had helped America win its independence from Britain. Towns and counties all had quotas, and if they reached their quotas they received honor flags. By May of 1918, 64 counties and 271 towns—among them Monroe, Smithfield, and Kings Mountain—had won honor flags. The final report showed that North Carolinians had raised over $27 million for the war effort. County chairmen reported that the Liberty Loan drives had made people more “community-spirited.” It also helped to improve relations between whites and blacks.

Another way to support the war effort was to grow and conserve food. The National Food Administration divided North Carolina into eight districts, with a food administrator appointed in each county. All citizens, including children and city dwellers, were supposed to raise food, not waste it. Planting a garden showed patriotism, and food left uneaten on a plate brought scowls of disapproval. Sugar was rationed from May to December of 1918. As a result of these efforts, North Carolina produced four times as much food in 1918 as it did in 1917.

Efforts to preserve all that food were also highly successful. While some was dried, the main method of preservation was canning, mostly by canning clubs. North Carolina had 142 of these clubs, with a total membership of 12,000 women and girls. Seventeen times as many cans were put up in 1917 as had been in 1916.

The state’s factories and mines also heavily supported the war effort. Surry and Cherokee counties produced manganese, Cabarrus and Rowan counties mined pyrites, and Jackson and Buncombe counties turned out chromium. These minerals were used for making military equipment and munitions. Textile plants all across the state produced clothing and tents for the army, while factories in Raleigh and Sanford made ammunition. At least two coastal towns built ships during the war: wooden ships were built at Morehead City and steel ships at Wilmington. The Liberty Shipbuilding Company in Wilmington was even building concrete ships by the end of the war!

All existing charitable and service organizations and almost all churches in the state helped with the war effort. When the war started, volunteers swamped the Red Cross. It sent people to work in field and base hospitals in France and at home and taught first aid to civilians. Of the doctors who volunteered to go to France at least two were women—Mary Latham of Highlands and Anna Gove of Greensboro. The YMCA was also extremely active in work related to the war. It operated “huts” at home and abroad for servicemen. It also recruited mechanics, railroad builders, and other skilled workers to go to France. Some new service organizations, such as the North Carolina Women’s Committee and the War Camp Community Service, did much to assist the older organizations.

The children of North Carolina worked just as hard as the adults and contributed a great deal. Boy Scouts participated in patriotic rallies and the Liberty Loan drives. The Woodcraft Girls distributed food pledge cards and enrolled as “Potatriots” entering a competition for growing the largest potato crop. The Camp Fire Girls baby-sat for women working in war plants and helped the Red Cross roll bandages and make dressings for wounds. Girl Scouts were involved in all those activities and sold war bonds, made scrapbooks for hospitals, and wrapped Christmas packages for soldiers.

Clearly the people of North Carolina believed strongly in the “war to end all wars”and wanted to “make the world safe for democracy.” That is why they worked so hard to help whip the kaiser.

At the time of this article’s publication, Richard L. Zuber served as a professor of history at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: Supporting the World War II Effort. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/05/SupportingWWIIEffort11.pdf

Additional resources:

"Finding Aid for the Anna Maria Gove Collection, 1864 - 1952." University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Jackson Library. http://library.uncg.edu/info/depts/scua/collections/manuscripts/ead/Mss002.xml

"Annie Bryant Robey Papers, 1918-1919." University of North Carolina Charlotte, J. Murrey Atkins Library. http://library.uncc.edu/manuscript/ms0225

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI. NC Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm

"World War I." North Carolina Digital History. Learn NC. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newcentury/3.0

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit, State Archives of NC. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm

Image credit:

Ingres, Maurice. 1917. "Let's end it quick with Liberty Bonds." Central Litho. Co., State Archives of North Carolina. Call no. MilColl.WWI.Posters.9.22. Online at https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/lets-end-it-quick-with-liberty-bonds/564785.

1 May 1993 | Zuber, Richard L.