See also: Medicine Shows; Crazy Water Crystals

Patent medicines were proprietary drugs, often containing alcohol, narcotics, or opiates, that enjoyed their greatest popularity in America between the 1870s and the 1930s prior to the era of modern medicine and federal pure food and drug laws. During this period, there were no laws requiring drug manufacturers to prove that their preparations were safe and effective, that ingredients be divulged on the container, or that their producers have any medical or scientific training. Because of this, many hucksters bottled their nostrums under unsanitary conditions and made exaggerated claims that their products would cure a number of widely divergent maladies. Many patent medicines had formulas that were never actually patented, but their manufacturers relied on trademark protection for their distinctive advertising and packaging.

One example of a patent medicine produced in North Carolina is the syrup bottled by Mrs. Joe Person of Franklinton in the 1880s for the prevention of scrofula. Scrofula was a type of lymph node disease that today is known to have resulted from the drinking of tainted milk before the advent of pasteurization. Like many other patent medicine manufacturers, Person used testimonial advertising in newspapers to promote her product. Also typical was her claim that the formula was based on an old Indian recipe so it would have more credibility with people who believed in the curative powers of Native American herbal medicine. On the bottle Person's remedy was said to "purify the blood" and cure rheumatism, skin eruptions, eczema, and stomach troubles, among other ailments.

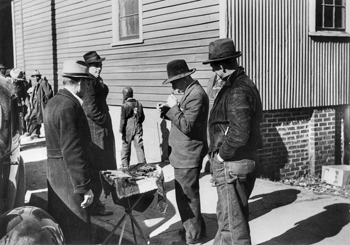

Some patent medicine makers went on the road in horse-drawn wagons to promote their concoctions by staging showy demonstrations in which mostly spurious "miracle" cures were performed by application or ingestion of their products. In the late nineteenth century these "traveling medicine shows" were an immensely popular form of entertainment throughout the nation.

Because of the exaggerated curative powers of many patent medicines, their potential for harm from some ingredients, and their widespread availability, the North Carolina Pharmaceutical Association tried to have sales restricted in general stores as early as 1876. But the public demand for the products and the strong lobbying of local merchants' associations prevented state legislation. A further attempt was made to curb over-the-counter sales of patent medicines in 1923, when elements of the North Carolina temperance movement allied with druggists to introduce legislation prohibiting groceries and general merchandise stores within five miles of a pharmacy from selling patent medicines.

Many prohibitionists in North Carolina felt that patent medicines were a threat to sobriety because they represented a loophole by which the public could legally buy products with a high alcohol content. Five years into Prohibition, an official of the North Carolina Anti-Saloon League denounced "the enormous sale of bottled concoctions carried in the stock of grocery stores and general merchandise establishments which in truth is largely ethyl alcohol colored."

State legislation continued to be weak and did little to restrain the deceptive business practices of the patent medicine industry. Not until 1938, when the labeling laws of the federal Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 were strengthened by passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, did many medicine makers become more accountable for the safety and effectiveness of their products.