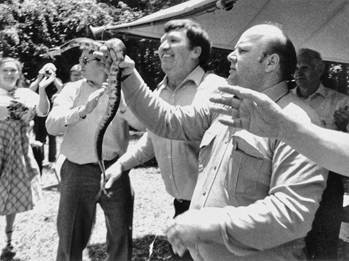

Snake handling is the practice of certain Christian sects most often found in the southern Appalachian Mountains. Their other rituals sometimes involve the drinking of strychnine, the handling of fire, speaking in unknown tongues (glossolalia), and the laying on of hands for healing of the sick. Members are usually from small, poor communities, feeling little connection to the world away from their mountains. It is believed that George Went Hensley began the twentieth-century practice of snake handling during the summer of 1909 in a remote section of southeast Tennessee, later establishing the "Church of God with Signs Following." His beliefs and practices spread to North Carolina and throughout the southern Appalachians, as well as to parts of the Midwest, where many unemployed mountain people had relocated to find jobs.

Several Bible verses are used by snake handlers to validate their beliefs and practices, in particular Mark 16:17-18, which describes believers "taking up serpents" as signs of faith. Snake handlers consider these words to be commands, not merely suggestions. They believe these words are binding to all who profess belief in the Gospels: God takes over their faculties, allowing them to carry out God's instructions without harm to themselves.

In October 1948, a three-day snake handling "convention" was held in Durham for "people who believed in and practiced the gifts and signs of the Spirit of God." The convention was hosted by Col. Hartman Bunn of Zion Tabernacle in Durham, and ministers and followers came from Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, as well as other towns in North Carolina. At the time, North Carolina Supreme Court cases were pending against Bunn and Benjamin Ralph Massey (who was known as the snake tender of Zion Tabernacle) for having earlier violated a city ordinance against the public handling of snakes. The convention went on as planned, but several arrests were made and numerous poisonous snakes were seized.

Later, in December 1948, Bunn went before the North Carolina Supreme Court, where he stated that the practice of handling snakes was an important part of his religion and that forbidding these actions violated the constitutional freedom of religion. The state attorney general, T. Wade Bruton, argued in return that even though the laws could not regulate what people believed, if their religious practices endangered them, the state could regulate those practices. The next year, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a law declaring that the handling of poisonous reptiles was a "public nuisance and criminal offense." Although in North Carolina, as in most states, the handling of poisonous snakes is illegal, the practice still continues in anonymity in some rural areas.