Classification

Class: Osteichthyes (bony fishes)

Order: Acepisenseriformes

Average Size

Length: Up to 9 ft.

Weight: Up to 500 lbs.

Food

Worms, crustaceans, insects, mollusks and small fishes.

Breeding

Spawning occurs in mid-river between February and July. Sturgeons remain in the river system during summer and return downriver in fall.

Young

Hatch in about one week at water temperature of 64 degrees. No parental care given to young.

Life Expectancy

Up to 60 years.

Range and Distribution

The range of the East Coast subspecies of Atlantic sturgeon (A. oxyrinchus) extends from the Hamilton River in Labrador, Canada and from northern Quebec to southeastern Florida. However, no Atlantic sturgeon have been recorded in Florida waters since 1900. The Gulf sturgeon occurs on lorida’s west coast. Atlantic sturgeon have also been recorded around Bermuda, and at one time an isolated relic population may have lived off northeastern South America. One specimen was recorded there more than 100 years ago.

General Information

Sturgeon have long been prized for their firm white flesh and eggs, or roe, which make excellent caviar. The Atlantic sturgeon is an intermediate cousin to the much larger North American, Pacific Coast white sturgeon, A. transmontanus, and the much smaller shortnose sturgeon, A. brevirostrum. There are 2 distinct subspecies of the Atlantic sturgeon—Acipenser oxyrhynchus oxyrhynchus and Acipenser oxyrhynchus desotoi. Both the white sturgeon, which may grow to a length of 12 ft. and exceed 1,000 lbs., and the Atlantic sturgeon, which may grow to a length of 9 ft. and weigh over 500 lbs., are commercially harvested for their eggs. The shortnose sturgeon is a much smaller fish, usually less than 3 ft. long.

Sturgeon are anadromous fish, which means they spend most of their life in salt water but migrate up freshwater rivers, along the coast, to spawn.

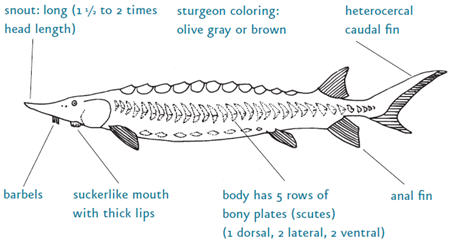

Description

Even though the Atlantic sturgeon is more common in North Carolina waters than the shortnose sturgeon, they are often confused with one another. Both have 5 rows of bony plates called “scutes” along the body. However, Atlantic sturgeon have 2 rows of prenatal shields, while the shortnose has only one. Also, the Atlantic sturgeon has a smaller mouth and a longer, more sharply pointed snout than the shortnose. Both also have a heterocercal (sharklike) tail. Unlike sharks, sturgeon have a much smaller dorsal (top) fin and are completely harmless. The Atlantic sturgeon has a protractile, suckerlike mouth, which it uses to feed along the ocean bottom. The bony plates and thick, leathery skin protect it from most predators and give it a very primitive appearance. In fact, it is a member of one of the oldest families of fishes, Acipenseridae, dating back to the dinosaur age.

History and Status

The population, size and range of Atlantic sturgeon have declined drastically throughout the 20th century. As a result of this decline, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission initiated a coast-wide fishing moratorium in 1998. Further concern over the condition of Atlantic sturgeon populations prompted the National Marine Fisheries Service to begin a status review of the species in 2007 to determine if a threatened or endangered listing is needed.

Habitat and Habits

Atlantic sturgeon is a long-lived species, often reaching 60 years. Males may mature earlier than females. Sturgeon feed mainly at night on a variety of bottom-dwelling organisms such as snails and worms, which they slurp up with their suckerlike mouths.

Adult Atlantic sturgeon migrate to upriver spawning areas in January and February. They require clean, deep, swiftly flowing freshwater, preferably over a hard, rough or rocky bottom, to successfully reproduce. Their adhesive eggs attach to rocks, gravel, or woody debris and hatch within a week at a water temperature of 64 degrees.

Atlantic sturgeon swim out to sea, where they undertake extensive migrations of up to 950 miles. Young sturgeon have been captured off the Georges and Browns banks of Nova Scotia.

People Interactions

Human-related activities—commercial fishing in particular—have led to a decline in Atlantic sturgeon populations throughout the fish’s range. In the past, sturgeon were prized for their firm white flesh and eggs, which were used to make caviar. For these reasons, they were fished almost to extinction. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the second largest caviar fishery in the U.S. was located in the Chesapeake Bay, just north of the North Carolina state line. Dams built for navigational or flood-control purposes on the larger coastal rivers restricted or often prevented sturgeon from reaching their traditional spawning grounds. Increasing levels of water pollution from growth and development across the state degraded spawning sites, causing decreased reproduction. Slow growth, late maturation and sporadic spawning are also factors that contributed to the decline of Atlantic sturgeon.

NCWRC Interaction: How You Can Help

Detailed information on the locations of Atlantic sturgeon spawning and nursery sites is sparse in North Carolina. If you encounter a wild sturgeon, please contact the Commission’s Division of Inland Fisheries at (919) 707-0220. Include the time, date, and location of the encounter, approximate length of the fish, and a good quality photograph (showing the mouth and anal fin for species verification). Please be mindful that no harvest of sturgeon is allowed. Any sturgeon captured incidental to fishing for other species must be returned to the water alive.