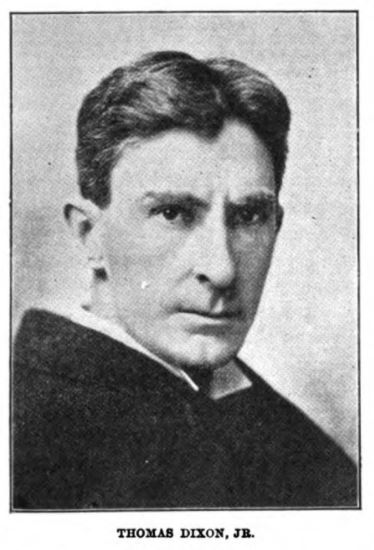

11 Jan. 1864–3 Apr. 1946

Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. was born on January 11, 1864, near Shelby to Thomas Dixon and the former Amanda Elvira McAfee. The elder Dixon was a Baptist minister who also ran a store in Shelby. Educated by his parents and at Shelby Academy, the younger Dixon also worked in his father’s store. In 1879 he entered Wake Forest College, where he would achieve highest honors. Dixon Jr. won a scholarship to graduate school at the newly established Johns Hopkins University, where he enrolled in 1883. It was at Johns Hopkins where he met and befriended future US president Woodrow Wilson. Once in Baltimore, however, Dixon became enamored with theater and, within a few months, moved to New York to pursue an acting career. Failing to establish himself as an actor, Dixon Jr. returned home to Shelby, where he began to study law.

Dixon was elected to the General Assembly in 1884 and passed the bar after serving in his first legislative session. It was not long before he tired of law practice and became a Baptist minister. In 1895 he left the ministry to become a nondenominational speaker. Having developed his oratory skills since college, Dixon became a famed lecturer during the 1890s, earning as much as one thousand dollars per engagement. While maintaining his speaking career he became a gentleman farmer in Virginia.

In 1901 Dixon wrote his first of 28 novels, The Leopard’s Spots. This was the first in a trilogy of novels inspired by events and people from his youth, especially his father and uncle (who were both members of the Ku Klux Klan). Advocating for white men to do their “duty,” the trilogy reinforced the concepts of the “Lost Cause” and described an alternate version of the historical record that romanticized white supremacy and condemned citizenship status of African Americans. The novels called for the exclusion of blacks from American society and for reconciliation between North and South. The second novel in the trilogy was The Klansman, which Dixon crafted into a screen play that eventually became the landmark motion picture, Birth of a Nation, directed by D. W. Griffith, a project that took from 1913 to 1915. The motion picture remains a classic in terms of study in film making technique as much as it remains an aberration in any factual depiction of historical events. Nonetheless, the movie was a sensation across the United States and was screened at the White House by Dixon’s college friend Woodrow Wilson. The popularity of Birth of a Nation and its false narrative is credited with encouraging a revival of the Ku Klux Klan after several decades of decline.

Other novels continued his poor view of African Americans as citizens, his views on women’s rights (he was not in favor of equal rights for women), and, in his final book – The Flaming Sword - he took direct aim at his African American critics, such as W.E.B. DuBois. The 1939 work decried a “vast conspiracy” of African Americans and Communists set at destroying America.

Dixon’s early writing success, his early works were best sellers, was off-set by a series of financial disasters that eventually left him with little money. He lost money the stock market crashes of 1907 and 1929. He ended his career as an almost indigent court clerk in Raleigh, N.C.

Thomas Dixon was married to Harriet Bussey from 1886 until her death in 1937. They had three children. In 1939 Dixon, in failing health, married Madelyn Donovan, a leading lady from one of his films. He died in Raleigh on April 3, 1946. He was buried in Sunset Cemetery in Shelby.