Word that Captain Johnston Blakeley and the men of the U.S. sloop of war Wasp had defeated the British sloops Reindeer and Avon in the summer of 1814 proved welcome news for Americans hungry for military and naval successes during the War of 1812. The good news was particularly welcome in North Carolina, since Blakeley had grown up in Wilmington. Eager to add its voice to those praising the young hero, the General Assembly on 7 Dec. 1814 voted "to present to Captain Blakely [sic], on his return to the United States, a superb sword, appropriately adorned, in the name and on behalf of his fellow citizens." Unfortunately, Blakeley never made it back to the United States. He, his crew, and the Wasp were last seen on 9 Oct. 1814. Although rumors abounded, their loss remained a mystery.

The General Assembly waited to acknowledge Blakeley's death until 28 Dec. 1816, when it resolved that the sword intended for the captain should be delivered to his widow, Jane Hoope Blakeley. They located Mrs. Blakeley in Boston, but instead of sending a sword they wrote her and asked if some other gift might be appropriate since the captain's only child, Udney Maria Blakeley, was a daughter. "You have been so kind as to desire my opinion on the subject of a present more proper than a sword for a female," she replied; "allow me to propose a set of tea-plate." The General Assembly endorsed the change of plan and agreed to spend as much as $500 for the gift.

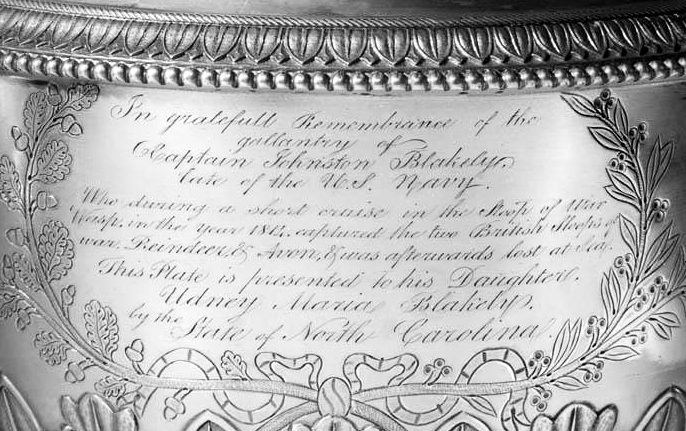

The French-style tea service was completed in 1819 and presented to Maria Blakeley on her sixteenth birthday. Consisting of a teapot, a coffee pot, a milk jug, a slop or waste basin, and a sugar bowl with cover and tongs, the service was the work of Anthony Rasch, a German-born and -trained silversmith who worked in Philadelphia from 1804 until 1820. Rasch's classically derived design may have been inspired by plate 34 in Recueil de Décorations Intérieures, an 1802 publication by Charles Percier and Pierre F. L. Fontaine, designers to Napoleon's court. The eagle finials that the larger vessels bore and the crossed anchors engraved on the back of each piece represented Blakeley's naval exploits and presumed death.

The silver service remained outside of North Carolina for a century and a half before returning permanently in 1968 as a gift to the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. Inherited by descendants of Maria Blakeley's widower and his second wife, the tea set was acquired through art dealers and donated to the museum by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lee Smith Jr. of Raleigh in honor of Robert Lee Humber of Greenville. The Museum of Art has lent the Blakeley service for numerous exhibitions in other American museums. Its usual location is the building's board room.