No one was untouched by the Civil War, especially in the South. With casualties and a significant population of men away at war, tremendous hardships were created for the women and children left on the home front. Children of all races and circumstances endured a vast array of experiences during the Civil War.

Children shared an excitement for the war, with enthusiasm and interest in the political and military affairs going on in the country. Boys, both black and white, showed excitement during military festivities and drills by running alongside militia teams as they paraded through the streets and fields. They created their own militia play and incorporated their own political views into their war play. The war brought a natural curiosity to the children in the South, where some watched the action from the sidelines. In The Children’s Civil War, James Marten tells the story of a mother whose two oldest sons begged her to allow them to investigate a battle near their home. Later that evening she deeply regretted her decision to let them go. When the boys returned home, they were not the same boys that left earlier that day. In Topsy-Turvy: How the Civil War Turned the World Upside Down for Southern Children, Anya Jabour describes that same enthusiasm children had for witnessing the war up close, depicted in a wartime photograph of several children getting as close as possible to see the soldiers at Sudley Ford, Virginia as they were on their way to what would become the Battle of Bull Run. The photograph comes from the collections of the Library of Congress, and in the image the boys wear military style hats.

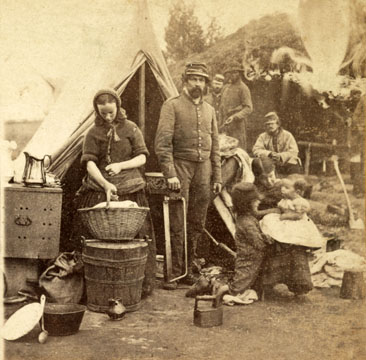

Children of the Civil War, both black and white, stepped up to contribute to the war effort and to fill the void of absent fathers and brothers on the home front. This proved especially true for many children in North Carolina. Throughout the South, like in North Carolina, older boys and girls worked in ammunition factories as well as in government offices. Children scraped lint to make bandages for wounded soldiers, and younger children gathered supplies and food for local soldiers. According to Marten’s research on this topic, a few formerly enslaved children, including Booker T. Washington, felt little impact when the war started because they were already laden with responsibilities and hard work. For other enslaved children, the war did bring an even heavier workload. In some cases, young enslaved people were forced into fields at a much younger age. Marten added that it was not unusual for an enslaved teenage boy to accompany his enslaver into war or for an enslaved teenage girl to sew for soldiers and nurse the wounded rebels.

As the war progressed and conditions worsened, both black and white children in the South faced greater and greater hardships and devastation. There was a shortage of food, a lack of clothing, much disease, and homelessness. White children and their families fled their homes and land to escape Union soldiers, while black children and their families fled to the Union soldiers for protection. Families were split apart and displaced. Black children felt disruption and chaos as well. Many formerly enslaved people fled plantations to seek refuge at "contraband" camps. These camps were an important part of North Carolina’s history in the Civil War. Refugees were able to earn wages, work for food and clothing, get an education, and worship. There were six camps established by the Union in North Carolina (at Hatteras, Plymouth, Washington, Beaufort, New Bern and Roanoke Island), and eventually all six camps came under Confederate attack.

Southern children suffered not only physical hardships but emotional hardships. Fear was a dominant emotion among both black and white children with the fear of home invasions by the Yankees, physical violence and death, and separation of family. Jabour recounts children’s fears in Topsy-Turvy with their stories, including some North Carolina children. George Robertson, an eight-year-old white boy from Asheville, North Carolina, feared the Union soldiers. He wrote how intimidating and loud the Union soldiers were when they took over his family’s home and how they thumped and clanged and banged all over the house as if to intentionally create chaos, yet they hurt nothing. In fact, they posted a guard at young George’s home to protect his family from further invasion. George reminisced how fond his family grew of this young Yankee soldier and that he actually addressed George’s mother as Mother and helped out with work around the house. Children in the south had a real fear of violence with the fear of being shot and killed as a Union sympathizer. Enslaved children feared the reality of being torn from their families.

The end of the Civil War brought different meanings and emotions for white and black children. The Civil War officially ended when General Johnston surrendered to General Sherman at the Bennett Place farm near Durham Station, North Carolina, in April of 1865. Once the news of Confederate defeat and the emancipation of enslaved people began to arrive, black children responded to the news with jubilation and hope for the future while white children were more despondent and dreaded the future. White children saw a role reversal and now perceived themselves as enslaved and oppressed by the Union troops and Northern politicians who forced the end to slavery on them. Black children perceived the Union troops as their liberators and trusted the politicians to protect them and their newfound freedom.

Although historians do agree that the Civil War was hard on everyone, especially Southern children, the greatest impact, however, was actually to the enslaved black child. Following the war, Reconstruction brought new challenges and hardships to black children, as their families were suddenly given a choice between continuing to work for former enslavers or being uprooted with the strong possibility of being subjected to crushing poverty. Continued racism meant that black children in the South encountered white hate groups, segregation, and racial violence in the aftermath of the war.

The Civil War touched the lives of children in both similar and vastly different ways. The Civil War molded children’s lives as adults and shaped their attitudes, opinions, and prejudices that would pass from generation to generation. The children of the Civil War shared enthusiasm for the war, were burdened with greater responsibilities, and endured physical and emotional hardships. The end of the war for a Northern child meant victory, excitement, and success. The end of the war for a Southern child meant defeat, disappointment, and a transformed way of living. For enslaved black children, the end of the Civil War meant freedom and hope, which did not come without years of tremendous sacrifices, challenges, changes, and hardships.