25 Aug. 1802-27 Dec. 1860

See also: Rachel Regina Jones Holton

See also: Newspapers Part 1: North Carolina's First Newspapers; Writers, journalists, and editors (list of articles in NCpedia)

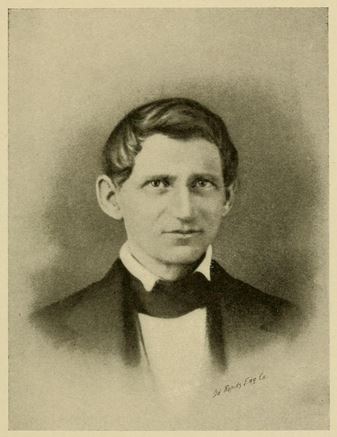

Thomas Jefferson Holton, born August 25, 1802, in Richmond, Virginia was the founder and editor of one of Mecklenburg County's earliest newspapers, The North Carolina Whig. Beginning under the name of Miners' and Farmers' Journal in 1830, the paper was changed to the Charlotte Journal in March of 1835, and later to The North Carolina Whig in January of 1852. Holton’s wife, Rachel Regina Jones Holton, took over the paper for two years after Thomas’ death in 1860 until the paper ceased to be published around 1863. During its operation, The North Carolina Whig reflected and influenced the views of a large portion of the Mecklenburg County population.

Holton was the son of Elijah Gorman Holton and Susanna H. Mosby, both of Virginia. They were married on April 16, 1798 in Woodford County, Kentucky. His father died in February of 1844, while his mother outlived him until her death in 1872. In 1823, Holton relocated from his native Virginia to Salisbury, North Carolina to work as a printer. He then moved to Charlotte where he worked on the Catawba Journal.

At the birth of The Miners' and Farmers' Journal, Holton stated “it is to be no party paper,” however Holton’s Whig views were expressed in the paper, with regular topics of federally sponsored infrastructural improvements including a national railroad and other transportation networks. The journal reported on farming, articles from northern periodicals, and local events. There are also conflicting sources on when the publication’s name was changed to the Charlotte Journal, with some scholars stating 1832, while others say 1835. Surviving issues indicate that The Miners' and Farmer's Journal continued to be published at least into the spring of 1835.

In addition to changing the name of his newspaper during this time period, Holton married his wife Rachel on June 24, 1834. The future Mrs. Holton was also native to Virginia. She moved to Cabarrus County to become a teacher, where she later met Holton.

In 1834, the journal ran a column regarding the passing of Lafayette. However, Holton’s paper played a more significant role in reporting on the events, as well as themes expressed by northern and southern citizens during the antebellum period, an era in which the United States repeatedly required compromises to stitch itself together. Laws such as the Missouri Compromise had sparked much disagreement on the expansion of slavery westward, with the latitude between Missouri and the southern states clearly dividing the nation. On October 25, 1830 an article in the journal “called attention to the state of affairs wherein talk about dissolution of the Union had become so common as not to excite horror, as it once did.”

In 1852, Holton once again changed the title of his newspaper, this time to The North Carolina Whig. At the launch of this new title, Holton stated “Our freight is Truth, Justice, Honesty, Patriotism, Good Faith, the Rights of the Constitution, and of the People, as developed in the administration of Millard Fillmore.” Although the Compromise of 1850 had nearly dissolved the Whig Party and Fillmore failed to gain support for re-election within the year, Holton's paper held on in Mecklenburg County. Meanwhile, the shift from the Whig Party to the Democratic Party was also beginning to be felt. Voters who four years earlier had voted for the Whig President Zachary Taylor were now voting for Franklin Pierce and later James Buchanan, both Democrats. And in 1854, the Kansas Nebraska Act struck the final blow to the Whig Party nationally, firmly dividing northern and southern Whigs, respectively into the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. In North Carolina, the Whigs party's brief revival in the 1860 election and its pro-union stance kept The North Carolina Whig afloat. It lasted another two years into the war due to the contributions of his widow, Rachel.

the Holton's reportedly had eleven children. Unfortunately, T. J. Holton passed away on December 27, 1860, just a week after South Carolina had issued the ordinances of secession on December 20, 1860, followed by the secession of North Carolina on May 20th. Newspapers reported that the cause of death was injuries sustained after being thrown from his buggy several weeks prior when traveling to Monroe. Holton was buried in the Elmwood Cemetery in Charlotte.