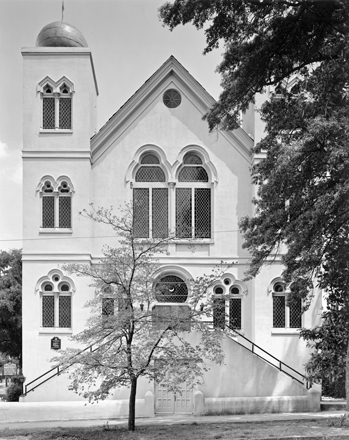

See also: Temple of Israel.

Jewish religious developments in North Carolina have reflected national trends marked by evolution from a European traditionalism to an American Judaism. Jewish immigrants brought with them the religious culture of their homelands, but in America they progressively liberalized their beliefs and practices.

Jacob Mordecai, who settled in Warrenton in 1792, was a learned and observant Jew who had been a founder and president of Richmond's Orthodox synagogue. Many, though not all, of his children were assimilated into the Christian community through marriage and conversion. Isolated and very few in number, early North Carolina Jews lacked an organized community to sustain their faith.

German Jews, who began arriving in the middle of the nineteenth century, came from religiously Orthodox communities. Jews from southwestern Germany had felt the liberating effects of the Enlightenment and Napoleonic emancipation, while Prussian Jews, whose migration tended to come later, were more firmly rooted in Polish Orthodoxy.

Early North Carolina Jews came mostly from Baltimore, Richmond, Philadelphia, or Charleston. The state's Jewish communities were colonies of these larger centers; North Carolina's Jews took religious direction from them and often returned to them to find spouses, rabbis, and kosher supplies. In turn, Durham, Goldsboro, and Wilmington served as religious centers for rural communities where few Jews resided. Religion, as well as kinship and commercial ties, kept Jews intimately bound as a distinct people.

Since Jews required burial in consecrated ground, the first formal act of local community organization was to form a Cemetery Society. This society was a traditional European institution (a Chevra Kadisha, Hebrew for "Holy Fellowship") that not only provided ritual burial but also organized worship and welfare for the poor and transients-the obligation of taking care of one's own being deeply ingrained in Jewish religious culture. Such societies formed in Wilmington in 1852, Raleigh and Charlotte in 1870, and Goldsboro in 1873. Circuit-riding rabbis, most notably Rabbi Edward Calisch of Richmond, traveled through the state organizing worship services and religious schools.

North Carolina Jewry in its early days was, for the most part, traditionalist in its religious orientation. Goldsboro's Jews stated that Sabbath and holiday observance was to be guided by "Biblical injunction, rather than by expediency." Traditionalists held services in Hebrew and maintained kosher dietary laws. Over time, however, local Jews acculturated and liberalized. Like most southern Jews, Jewish North Carolinians aligned themselves with the Reform movement after the founding in Cincinnati of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1873. Dietary laws were typically abandoned. As civic-minded Americans of the Hebrew faith, Reform Jews espoused a universalistic, prophetic Judaism that deemphasized Jewish parochialism. Zebulon Vance, in his "Scattered Nation" lecture of 1874, described American Jews as "simply Unitarians or Deists." Social and economic forces worked against Orthodoxy. The state's Jewry was almost entirely mercantile, and with payday at the mills on Friday night and market day on Saturdays, Sabbath observance became economically difficult. Communities tended to be divided between traditionalists and modernists.

The arrival of East European immigrants after 1880 transformed the Jewish character of the state. They were Yiddish-speaking Jews who came from self-governing East European Jewish enclaves, urban ghettos, and rural shtetls. Their orientation was traditionalist, if not strictly Orthodox. In larger towns like Durham, they concentrated in a Jewish neighborhood anchored by a synagogue and kosher bakery, grocery, and butcher shop. Orthodox Jews maintained regimens of daily prayer with a quorum of ten men. A local or itinerant ritual slaughterer, a schochet, ensured a supply of kosher meat. The early immigrant rabbi was often an unordained, self-proclaimed "reverend" who served as a religious master of all trades. As one Durhamite recalled, "He circumcised you, married you, buried you, and killed your chickens."

If the migration from Eastern Europe to the port cities of Baltimore or New York represented one break from a traditional society, the secondary move to the remote, small Jewish communities of North Carolina represented another. Although some Jews struggled to maintain their Orthodoxy, larger numbers were less scrupulous in their observance of ritual and dietary laws, although they were still pervasively immersed in the East European Jewish ethnicity known as Yiddishkeit.

In larger communities, social and denominational fault lines often existed between the acculturated, native-born Jews of German origin and the newly arrived, Orthodox immigrants from Eastern Europe. Where numbers were small, Jewish unity forced compromise. Historical trends worked in favor of liberal, Reform Judaism. In 1941 Rabbi Robert Jacobs of Asheville wrote that "our membership is an amalgamation of 'Reform' and 'Orthodox,' with the emphasis on Reform Judaism. The Reform group . . . has lost its early rigidity, and the Orthodox group . . . has lost its scrupulous observance of the minutiae of Jewish law. . . . With our Temple, an American type of Judaism is a-borning."

With the Americanizing of the immigrants, religious practices eroded, although ethnic bonds remained strong. Jewish group solidarity was preserved not just by the synagogue but also by such societies as the men's B'nai B'rith and the women's Hadassah. These philanthropic groups linked local Jews to international Jewry. The North Carolina Association of Jewish Women (1921) and the North Carolina Association of Rabbis (ca. 1951) encouraged religious observance and education. Jews, regardless of affiliation, were united locally by federations that provided social services and connected them to a national institutional network.

In the 1930s Orthodoxy began yielding to Conservative Judaism, which sought to accommodate religious law to modernity. Its theological approach was historical rather than fundamentalist, and it also moved hesitatingly toward gender equality. In the post-World War II years, Jewish education became a priority with the rise of an assimilated youth. Conservative Judaism grew ascendant in the immediate postwar years, with Reform Judaism enjoying stronger growth more recently. Many High Point Jews evolved from Orthodoxy, to Conservatism, to Reconstructionism, an innovative offshoot of Conservatism that viewed Judaism as a civilization and not just as a religion. As women have achieved equal liturgical status in the Reform and Conservative movements, they now serve as rabbis, synagogue presidents, and leaders of Jewish federations.

As the Sunbelt drew thousands of Jews southward, North Carolina Jewry became more reflective of national Jewish demography. Mobility, intermarriage, and suburban dispersal have attenuated Jewish bonds and religious difference. Population growth has also made the state's Jewry religiously pluralistic. Durham's Beth El Congregation is led by a Reconstructionist rabbi and holds both Conservative and Orthodox services. The Lubavitcher Hasidim, an ultra-Orthodox sect that combines religious enthusiasm with strict adherence to Jewish law, located emissaries in Raleigh and Charlotte to encourage traditional observance. Though traditionalism has shown renewed life, the overwhelming number of North Carolina Jews are religious liberals, affiliating with the Reform or Conservative movements.