Governor: 1862-1865; 1877-1879

See also: Zebulon Baird Vance, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography

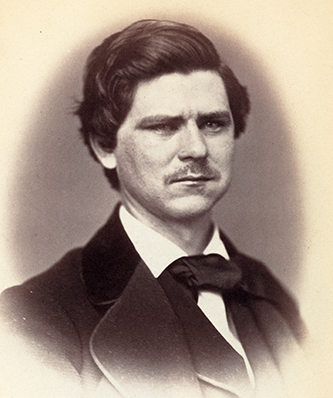

Buncombe County solicitor at 21, state legislator at 24, Congressman at 28, Confederate colonel at 31, governor at 32, three times governor of North Carolina, and United States senator for fifteen years, Zebulon Baird Vance (1830-1894) was the most popular political leader that the state has produced. Born on May 13, 1830, at the family homestead along Reems Creek in Buncombe County, he was the son of David Vance II and Mira Margaret Baird Vance. Although he received some formal education in local schools, he acquired most of his basic knowledge from his mother who supplemented his schooling in Asheville following his father’s death in 1844. Vance entered the University of North Carolina early in 1851 and for the rest of the year pursued the study of law under Judge William H. Battle and Samuel F. Phillips. More important than the law license he obtained in December 1851, however, were the contacts and friendships that would be influential later in his career.

A few months after setting up his legal office in Asheville in early 1852, Vance was elected solicitor for Buncombe County. The next year he received his license to practice law in the superior courts of the Seventh Judicial District which covered thirteen mountain counties. Zeb Vance never saw the practice of law as his mission in life. To him it was an entrance to the political arena, and he used courtrooms as opportunities to build a wide reputation and to meet prominent persons. He ventured into state politics in 1854, using his personality, oratorical abilities, and mountain wit to eke out a victory over Daniel Reynolds for a seat in the senate.

Vance equated the Democratic Party with sectionalism which he believed dangerous to the best interests of North Carolina and the South. Determined to oppose it, he cast his allegiance with the declining Whig Party. He continued to call himself such after the party had dissolved and he had entered other campaigns as a member of the American or Know Nothing Party. Vance was elected to the House of Representatives in 1858 to fill a vacant seat. His harsh criticism of Democrats as promoters of sectionalism resulted in a hot re-election campaign against David Coleman that almost ended in a duel. Vance served in Congress from 1858 to 1861, during which time he strongly advocated maintenance of the Union. He spoke against the act of secession because he thought it unwise and dangerous, but he never denied the legal right of a state to secede. The firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call to arms forced a choice of loyalty, and he cast his lot with his state and region.

Zeb Vance refused to be nominated as a candidate for the Confederate Congress; instead he raised his own company, the Rough and Ready Guards, of which he was the captain. He was elected colonel of the Twenty-Sixth Regiment on August 27, 1861, and saw considerable action. Still, politics was never far from the mind of Zebulon Vance, and he was criticized frequently for mingling politics with his official duties.

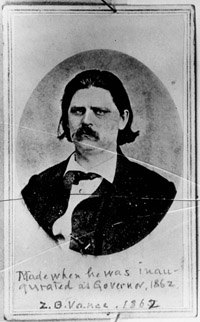

Anti-administration opponents had established a loosely knit organization called the Conservative Party, and they picked the popular colonel to head the 1862 gubernatorial contest against Democrat William Johnston. The campaign was fought in the press, and with the full support and vitriolic pen of William W. Holden, editor of the North Carolina Standard, Vance was elected by an overwhelming majority, more than 32,000 votes.

His antebellum stance as a strong Unionist had created some fears that his election would bring an effort at reunion, but Vance gave that no encouragement in his inaugural address. He acceded to the judgement of the people in the vote for secession and pledged to continue the war. He appeased Confederate authorities by promising to enforce the unfavorable Conscription Act while softening the anger of his fellow citizens by questioning the authority of the central government to pass the law.

Governor Vance diligently supported the Confederacy and made every effort to keep North Carolina loyal, but when the consolidation tendencies of the central government created hardships for North Carolinians and endangered its citizens, he took exception and complained bitterly; consequently, he quarreled frequently with President Jefferson Davis. Having abandoned his old Whig nationalism when the South seceded, Vance became a staunch defender of states’ rights, particularly regarding civil laws and judicial procedure. These, he reasoned, could not be sacrificed to any cause no matter how well justified.

On the home front, the governor had to deal with a flood of problems caused by the war: scarcity of goods and clothing, high prices, currency depreciation, and sinking morale. With alternatives having been exhausted, he turned to the practice of blockade running to provide needed supplies for both troops and civilians; he organized and established supply depots in the counties to distribute goods; and he offered sympathy and assurances to the people to boost spirits. Still, there was a sizable element of the population suffering from discontent, frustration, alarm at the growing presence of Union troops in the state, resentment of the Davis government for failure to protect them, and defeatism as the hope of victory slipped further away. Led by William W. Holden, who had broken ties with the man he practically had made governor, the group initiated a peace movement to take the state out of the Confederacy. Holden took the issue to the voters by challenging Vance in the election of 1864, but the governor’s efforts on behalf of the people had increased his immense popularity and he was re-elected by a four to one margin.

With the fall of Fort Fisher and Wilmington in January 1865, not even Zebulon Vance could lift morale or persuade the legislature to pass laws to help the dying Confederacy. As Gen. William T. Sherman moved his Union troops closer to the Capital City, the governor began moving military supplies and official records to the west on April 10. Two days later, he left Raleigh. On May 13, 1865, Vance was arrested at his home in Statesville and transferred to Old Capitol Prison in Washington. Although no charges were ever levied, he was held there until July 6.

After the war, Vance moved his law practice to Charlotte. Laboring under political disabilities imposed by the Fourteenth Amendment which prevented him from taking the United States Senate seat to which he was elected in 1870, Vance worked behind the scenes to develop the Conservative party until his disabilities were removed in 1872. By 1876 the Conservative Party had become the Democratic Party with Zeb Vance at its head. He ran for governor successfully in 1876 in a notable campaign against Thomas Settle. In the first two years of his administration, railroad construction resumed; progress was made in the education of both races; promotion of agriculture and industry brought North Carolina into the era of the New South; the financial structure of the state was placed on a more solid footing; and the last federal troops left the state.

In 1879, with two years remaining in his term, Vance left the governor's office for a seat in the United States Senate where he acted as a mediator attempting to heal the sectional wounds caused by the war. He offered explanations of southern motivations and feelings in the difficult times, but he never apologized for the war. Simultaneously, he urged the South to allow its wounds to heal and look forward, not backward, in its relationship to the North. For fifteen years Zebulon Vance represented North Carolina, speaking for the South, yet seeking the best interests of the nation. He died in office on April 14, 1894. His body was returned to his home state and buried in Riverside Cemetery in Asheville. Vance had married Harriette (Hattie) Espy on August 3, 1853, in her home county of Burke. They had four sons. She died on November 3, 1878, and two years later, Senator Vance married Florence Steele Martin who survived him.