Sand dunes along the North Carolina coast are an integral part of the ecosystem immediately adjacent to the sea. The dunes are formed when sand particles that have been washed ashore are picked up by the wind and blown inland until an obstruction is encountered. The obstruction usually consists of some form of jetsam that has been deposited high up on the beach during a storm, though it can also be types of vegetation. Eventually the dune itself becomes enough of an obstruction to block the windblown sand.

Normally, along the North Carolina coast the dunes are located less than 100 yards from the average high-tide line. Experienced observers cite a general rule: the finer the sand, the more gradual the slope of the beach, and the more coarse the sand, the steeper the slope of the beach. An ideal oceanfront sand dune is considered by many coastal residents as one where the beach slopes up gradually until the crest of the dune is reached. In such areas, even during storms, the waves tend to flow up the beach and then drain back again, causing no damage until the dune is breached and the seawater floods the area behind it, known as the "back beach." On the other hand, when the sand dunes are located too close to the water, the seaward side is often cut away, especially during larger storms, leaving a sand cliff that can be higher than the height of a man. Under such circumstances, the wave action in subsequent storms is liable to intensify the erosion, eating away at the sand cliff until the dune disappears.

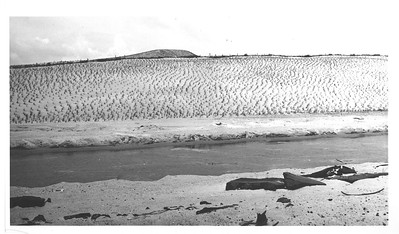

Once the oceanfront dunes are eroded away on the barrier islands, especially in areas where the islands are narrow and the beach is low, each successive storm brings water from ocean to sound, or, under certain conditions, from sound to ocean. At such times forest growth and other vegetation is destroyed, wide areas of low, flat beach appear, and in extreme cases new inlets are formed. In the days of sailing vessels, these low, denuded areas were used for hauling small craft between the sound and the ocean, and therefore were called "haulovers."

By the 1930s, large parts of the coastal islands were so denuded of vegetation that steps were taken to restore the oceanfront dune system. In preparation, the North Carolina General Assembly enacted legislation prohibiting further use of the coastal area as an open range for livestock. Concurrently, a massive beach restoration program was begun, with Depression-era transient workers and Civilian Conservation Corps teams doing the bulk of the work. In the process, hundreds of miles of sand fences were constructed and tons of beach grass seedlings were planted, providing a man-made obstruction to catch windblown sand.

Later, with the growth of oceanfront development, it became a common practice for property owners, seeking the best view of the ocean, to bulldoze the sand dune or build their cottage on top of the dune and as close to the ocean as possible. Subsequently, many of these homes have fallen down in severe storms or hurricanes, almost always resulting in widespread TV, radio, and newspaper coverage of their loss.

Oceanfront sand dunes, seldom reaching a size of more than 15 feet or so in height and a couple of hundred feet in width, should not be confused with the massive migratory sand hills along the upper North Carolina coast. Technically, these also are sand dunes; however, they have been formed over a period of hundreds of years and traditionally have been known as sand hills and not as sand dunes. The best known of these was the site of the Wright brothers' early experiments with man-carrying kites and gliders. It was always known as Kill Devil Hill, and never as Kill Devil Dune.