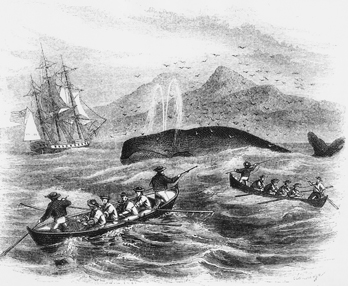

Whaling began as a shore-based activity on the North Carolina coast as early as 1666. With the eventual depletion of whale populations off their immediate coast, New Englanders soon made the transition to pelagic (open-sea) whaling, a change that foreshadowed their rise to international domination of the industry during the so-called golden age of whaling in the mid-nineteenth century. North Carolinians, however, continued shore-based forms of whaling with little interruption until 1916, when the last reported capture occurred near Cape Lookout. Pelagic whale ships from New England continued to visit the North Carolina coast, pursuing sperm and right whales in the "Hatteras ground" near the edge of the Gulf Stream.

Documentation from the colonial period reveals that North Carolina whale products were lucrative enough to provoke lawsuits among the citizens, to tempt government officials into fraud and embezzlement of tax revenues, to be used as a political issue, and to be recognized as an official medium of currency. During the Proprietary period, annual captures off the North Carolina coast may have exceeded 25 whales in good years.

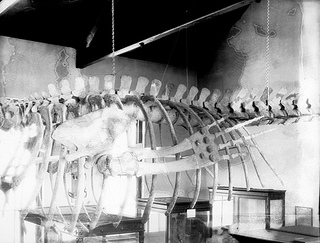

From at least the Civil War until the demise of the industry, North Carolina's shore-based whaling was centered on Shackleford Banks just west of Cape Lookout. The year-round fishing and seasonal whaling industries were sufficient to induce the establishment of several permanent settlements on Shackleford, including Diamond City, whose population may have numbered as many as 500 during its prime. One particularly curious feature of North Carolina shore whaling was the fishermen's habit of naming individual right whales at the time of their capture. Recorded examples include the "Little Children" whale that was killed by young boys; the "George Washington" whale that was captured on the president's birthday; and the "Cold Sunday" whale that was taken on a day "so cold that flying ducks froze solid while in flight." Other named whales included the "Lee," the "Big Sunday," the "John Rose," the "Mullet Pond," the "Lady Hayes," and the "Haint Bin Named Yit." Best known, however, was the "Mayflower" whale, whose skeleton is on permanent display at the North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, where harpoons and other whaling instruments used on the Outer Banks are also exhibited.