Compulsory apprenticeship had as its immediate objective the relief of indigent orphans, abandoned or illegitimate children, and the children of impoverished parents-the support and maintenance of whom would otherwise have fallen to the community. Its long-term objective was to train children in an occupation so that they could support themselves as adults. Such children, white or free black, male or female, were bound under court order to a master. The master stood in loco parentis and was entitled to the child's obedience and service, while being expected to offer moral instruction and paternal control. The courts sometimes removed apprentices from cruel masters. Boys were apprenticed to learn skilled crafts such as carpentry or farming, while girls were usually apprenticed to learn housekeeping or "feminine arts" such as weaving. In England only master craftsmen, certified by local guilds, had been able to take an apprentice, but in America-where trained artisans were fewer and social institutions were weaker-a more informal system evolved in which anyone could train apprentices. In North Carolina and the rest of the South, widespread use of indentured servants and enslaved people weakened the practice of apprenticeship, especially in rural areas.

With the end of slavery in 1865, the Freedmen's Bureau preempted the courts' power to apprentice indigent black children and orphans. From September 1865 to September 1867, the bureau apprenticed hundreds of these children ranging in age from infancy to late teens. Some were bound to learn skilled trades, many to learn farming and housekeeping, and a great number merely to serve as "apprentices or servants."

Although the system of compulsory apprenticeship lasted into the early 1900s, it was used less and less as the number of orphanages with their own agricultural, mechanical, industrial, and commercial training programs increased. The system was dropped altogether upon passage of the Child Welfare Act in 1919.

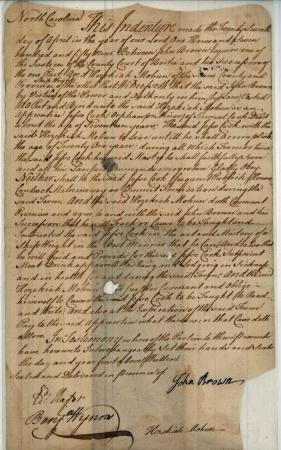

Voluntary apprenticeship in North Carolina was based on common law rather than statute law until the twentieth century. A father, white or free black, being entitled to the service and obedience of his child until age 21, was able to forge a binding agreement that his child should serve another for one or more years. The Apprenticeship Act of 1889 forbade voluntary apprenticing of children younger than 14 and set the term of their apprenticeship at three to five years. Since 1939 apprentices have been required to be 16 or older.

When enslaved people were apprenticed, the right of the enslaver to the services of his enslaved person was absolute, and assent of the enslaved person was unnecessary. Apprenticed enslaved people were generally made to learn skilled crafts that could not be learned on the plantation, such as shipbuilding, house carpentry, and coach making. Although enslaved craftsmen could not be masters of apprentices, they were sometimes the teachers from whom other black apprentices learned.

Labor union policies, reluctance of employers to train apprentices who then sought employment elsewhere, and unfair wages and terms of apprenticeship led to the National Apprenticeship Act (or Fitzgerald Act) of 1937. In North Carolina provisions of the federal act were implemented in the 1939 Voluntary Apprenticeship Act, which provided for the creation of apprenticeship committees to work with school authorities, employers, and employees in setting up local programs. Agreements were to be signed by the apprentice (and, if a minor, by his or her father) and the employer, and to become effective only after review by the director of apprenticeship.

By the twentieth century's end, only those occupations that remained essentially on a handicraft basis (such as machining and the building trades) or those industries where production varies from unit to unit (such as printing, tool and die making, and molding work) needed apprentices. North Carolina's modern apprenticeship program, coordinated under the Department of Labor, is supported by cooperating industries and businesses, labor unions, technical institutes, and high schools.