The Freedmen's Bureau, officially the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, was created by Congress in 1865 after months of debate. The Freedmen's Bureau controlled abandoned and confiscated lands in the South, with authority to divide them into 40-acre plots and rent them to freed blacks and white refugees loyal to the Union. It was also authorized to provide rations and clothing to homeless, sick, and destitute freedmen and refugees. The bureau coordinated educational efforts for freed people, monitored justice in the state courts, and supervised labor relations, overseeing contracts, adjudicating disputes, and providing transportation to jobs. For its time, the grant of such power was revolutionary. Still, the Freedmen's Bureau was a temporary device to help the transition from war to peace and from slavery to freedom; it was authorized to last for one year after the Civil War ended.

Organized geographically, the Freedmen's Bureau was headed by its federal director, Gen. Oliver Otis Howard. Below him, each state had an assistant commissioner. The state was then subdivided into districts administered by a superintendent; assistant superintendents coordinated the activities of subdistricts. Despite this elaborate organization, the bureau was always underfinanced and understaffed; no more than 900 agents served at any one time. Thus, large areas of the South had no bureau supervision.

Throughout the South, the Freedmen's Bureau was widely hated by whites, who believed that it interfered with their efforts to facilitate a return to "normal" relations between the races. White southerners regarded bureau agents as meddlesome, misguided idealists who did not understand the "true nature" of blacks and therefore encouraged them in false hopes and prevented them from settling down to hard labor. Historians, on the other hand, have often criticized the bureau for not promoting true independence and land ownership for the newly emancipated blacks.

When Congress tried to extend the term of the Freedmen's Bureau in 1866, President Andrew Johnson vetoed the bill, creating a political controversy that, along with other factors, eventually led to a split between the president and congressional Republicans. Congress eventually enacted the Freedmen's Bureau Bill, which prolonged the agency's life and increased its powers.

In North Carolina, the Freedmen's Bureau, although as understaffed as elsewhere in the South, had a profound impact on both blacks and whites. The state had one assistant commissioner, four superintendents, and several assistant superintendents in charge of between two and four counties. Frequent turnover plagued the state bureau. Between 1865 and 1867 there were five assistant commissioners and two acting assistant commissioners; the same pattern held true for superintendents and assistant superintendents. Despite this problem, the bureau performed a number of important tasks. Initially, it organized camps for destitute freedmen, providing rations, medical care, and work for thousands. It then attempted to establish what it considered to be fair labor relations between the races. While the bureau returned all the abandoned and confiscated land to former owners-following Johnson's orders and his pardon of white southerners-the organization worked to ensure that the contracts signed by freed people did not re-enslave them. On the other hand, bureau policies strongly encouraged blacks to work-which meant, for the most part, to do farm labor for white landowners.

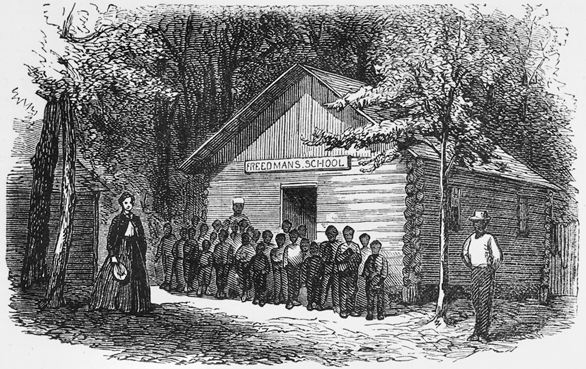

The Freedmen's Bureau also arbitrated disputes between white employers and black employees, trying to prevent physical abuse, to ensure payment of wages due, and to stop the most blatant abuses of the apprenticeship system. Bureau officers regularly sat in on sessions of the state courts to prevent discriminatory justice. Finally, the bureau helped promote black education. Most schools for blacks opened immediately after the war were founded by four northern missionary societies: the American Freedmen Union Commission, the National Freedmen's Relief Association, the American Missionary Association, and the Friends' Freedmen's Aid Association. Although the bureau had little money to assist these groups directly, it often provided school buildings or helped find sites for schools. Sometimes, it furnished living accommodations for teachers in the school buildings. F. A. Fiske, a northern white who served under the Freedmen's Bureau as superintendent of education in North Carolina, dispersed the funds received from the various northern benevolent organizations, coordinated the assignment of teachers, and supervised the curriculum and school schedules.

White North Carolinians generally opposed most bureau activities. They resented agents' "interference" in labor relations. They complained that freedmen were constantly running to the bureau with minor or even fabricated grievances and that agents tended to believe the word of blacks over that of whites. They charged that the bureau impeded the enforcement of state laws, such as those dealing with apprenticeship. Most whites were offended by the establishment of schools for blacks; they felt that the work of the bureau and missionary societies gave blacks ideas about political rights and equality that had no place in the social order. Whites displayed their opposition by drafting petitions and resolutions against the Freedmen's Bureau, by attacking blacks and bureau agents, and by burning schools and generally opposing education for blacks. Many bureau agents faced continual hostility and were ostracized from white society. Blacks, on the other hand, generally trusted the bureau and welcomed its assistance.