1836–27 June 1865

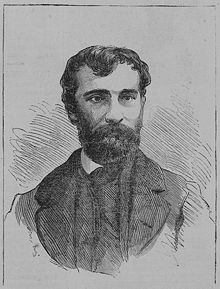

Henry Andrea Burgevin(e), adventurer and mercenary, was the son of Andrea Burgevin, a Napoleonic captain who migrated to the United States in 1815, and his wife, the former Juliet Guillet of New Bern. Henry was probably born in his maternal grandparents' home in New Bern; he joined three older children, Caroline; Edmund, who would be adjutant general of Arkansas during the Civil War; and Mary. Because of his father's early death (ca. 1836), he was raised by his mother. In 1844 he became a page in the U.S. House of Representatives. He served for a portion of 1844 and from January to March 1845, when he was transferred to the Senate. He remained there until 1853. In Washington he attended private and public schools.

In 1853, Burgevin visited Hawaii, Australia, India, and the Middle East. He enlisted in the French army in 1855 and fought in the Crimean War. At the war's end, he returned to Washington, D.C., and began reading law. He expended his savings before completing his studies and moved to New York, where he worked for a newspaper and later in the U.S. Post Office. In 1859 he sailed to China aboard the Edwin Forrest, arriving at Shanghai on 18 Oct. 1859.

In April 1860, Burgevin became an officer in Frederick Townsend Ward's mercenary force, organized to defend Shanghai and its environs from the Taiping rebels. After an initial failure, the force captured the Taiping stronghold of Sungkiang. In late 1861, Ward and Burgevin began to achieve notoriety after Ward, at Burgevin's suggestion, organized a Western-led Chinese force that became know as the Ever-Victorious Army (EVA).

In engagements in 1861–62, Burgevin received at least three wounds. At Hsiao-t'ang (1 Mar. 1862) he suffered a rifle wound from which he never fully recovered. In 1862 the emperor awarded Burgevin a fourth degree and later a second degree mandarinship for his accomplishments against the Taipings. Following Ward's death in September 1862, Burgevin assumed command of the EVA and directed several successful sorties against the Taipings. However, a rift between Burgevin and his employers overshadowed the victories. The Manchus wanted Burgevin to assist them in an assault on the Taiping capital of Nanking, but Burgevin refused to participate until the EVA received its back pay and acquired additional funds for equipment. By late December the pay was almost three months in arrears. On 2 Jan. 1863, Burgevin and the Chinese banker responsible for provisioning the EVA quarrelled over the monetary arrangements. Burgevin punched the banker and removed from the banker's residence forty thousand silver dollars which the banker had previously stated were to be used to pay the EVA.

The governor Kiangsu province, Li Hung-chang, used the incident to remove Burgevin from his command. Contending that he was only temporarily off duty, Burgevin placed an English officer in charge of the EVA and went to Shanghai to regain clear title to the command. Western officials in Shanghai were unable to alter Li's decision, but they did convene a mixed court of arbitration that awarded Burgevin approximately $32,600 in back pay. The Chinese refused to honor the award.

Meanwhile, Burgevin had taken his case to Peking and presented it to the Tsungli Yamen (foreign office). The Tsungli Yamen approved his reinstatement and sent a dispatch to this effect by messenger to Li. Li, however, disregarded it. Burgevin, who had accompanied the messenger, returned to Peking a second time but discovered that the Tsungli Yamen had lost interest in his case. Infuriated, he left Peking determined to obtain revenge. On 2 Aug. 1863, he and some associates joined the Taipings, but his stay with them was brief. In October he began negotiating with the new commander of the EVA, Charles George ("Chinese") Gordon. Initially, Burgevin proposed that the two establish a new kingdom in China. When Gordon refused, Burgevin requested and received an amnesty for himself and his followers. He crossed to Gordon's lines on 18 Oct. 1863.

On 1 Dec. 1863 the American consul general in China deported Burgevin to Japan. Burgevin returned to Shanghai in 1864, whereupon he was jailed and given a choice of standing trial for insurrection or returning to Japan. Burgevin chose Japan. Upon his return there, he conceived the idea of organizing an army to help the tozama daimyo (outer lords) overthrow the ruling Tokugawa shogunate. He sailed aboard the Feipang from Yokohama to Shimonoseki to discuss the matter with the tozama daimyo and was asked to return for their answer in a month or two. He reboarded the Feipang in the belief the ship was sailing to Hong Kong and then returning to Shimonoseki. However, once the vessel was at sea, the captain set his course for Shanghai.

In March 1865, Burgevin became a fugitive in Shanghai. He subsequently considered rejoining the Taipings and went to Amoy to contact them. Initially he was unsuccessful, but on 15 May 1865, a man known as Stanley led him into a trap under the guise of escorting him to a Taiping encampment. With Stanley's assistance, Burgevin was arrested. The Manchus sent him to Soochow for trial in one of their courts. En route, the boat carrying Burgevin purportedly overturned while shooting a rapids in Chekiang province, and Burgevin, who was in chains, drowned. Skeptical American officials investigated the incident but could not prove there had been foul play. Burgevin was interred in Shanghai's foreign cemetery.

Burgevin had married a Chinese courtesan in 1862. There is no record of offspring. In the 1860s journalists added a final e to Burgevin's name.