18 Jan. 1908–14 Nov. 1955

Samuel ("Sam") Armanie Byrd, Jr., actor, producer, and playwright, was born in Mount Olive, Wayne County, the son of Samuel Armanie Byrd, a local attorney, and his wife, Frances Lambert. His father's family had settled in Lenoir County in the late eighteenth century and had produced local leaders. Byrd grew up under the care of his mother, his father having died when he was a year old. When he was fourteen, his mother married William A. Zachary, and the family returned to Zachary's home in Sanford, Fla. Though Sam spent his remaining childhood years in his stepfather's Sanford home, his closest ties were in Mount Olive, and his literary works and stage characterizations most often reflected his earlier childhood experiences. His first award came in 1923, when the Mount Olive chapter of the Junior Order, United American Mechanics, gave him a prize for his declamation "Spartacus to the Gladiators."

Byrd was graduated from Sanford High School in 1925 and entered the University of Florida that fall, where he remained three years. While at the university, he became closely identified with college athletics and the Masqueraders, the campus drama organization (an earlier ambition had been to enter the diplomatic service).

On a trip to New York in 1929, he secured a small role in Winnie Baldwin's House of Mander, followed by appearances in Café and The Duke and the Novice. His first good role was in Elmer Rice's famous production of Street Scene, when he toured with the original cast in 1931. He did summer stock and small parts until 1933, when he was cast as Dude Lester in the Jack Kirkland play based on Erskine Caldwell's novel Tobacco Road, which opened at the Masque Theatre in New York on 4 Dec. 1933. The show was an instant critical success, and Byrd's interpretation of Dude secured for him a place in American theater history. He played in Tobacco Road for 1,151 performances and was awarded the Literary Digest Award as the Best Young Actor on Broadway during the 1933–34 season. In the 1937–38 New York theater season, he had the featured role of Curley in John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, and during the same season, Byrd produced his first major play, Journeyman, based on the novel by Erskine Caldwell. It was not a box office success. In 1931, Byrd purchased the rights to Samson Raphaelson's White Man and produced it, with himself in the leading role. The play, based on a story of blacks who pass for white, failed. In 1940 he produced Roark Bradford's dramatization of the John Henry stories, which brought Paul Robeson, the controversial black actor, back to the United States from London to sing the title role. Byrd's understanding of and sensitivity toward black subjects was ahead of its time in the American theater, and in spite of the quality of his productions, they failed to achieve the financial success he desperately needed to continue. In 1941 he produced Good Neighbor. Always a humorist, he said after his failures at producing plays, "I know there's money in show business, because I put it there."

Small Town South was begun in 1941, finished in January 1942, and published by Houghton Mifflin Company the same year. The book, based on Byrd's life in Mount Olive and Sanford, received the Life in America prize in 1942.

During 1942, Byrd entered the U.S. Navy as an ensign. He received the Bronze Star medal for working thirty-six hours expediting the evacuation of casualties from the Normandy beachhead during the D-Day Invasion in June 1944. It was on his experiences in the navy that he based his novel Hurry Home to My Heart, published in 1945, which centered principally in Mount Olive and Seven Springs. Byrd was promoted to lieutenant and transferred to the Pacific Theater in 1945. He saw service in the Battle of Okinawa and, as beachmaster of a landing operation, received the surrender of Japanese forces at Sasebo.

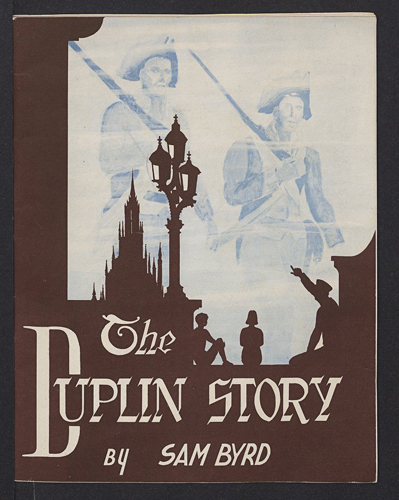

In 1946, Byrd received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in creative writing, which included a five-month study of postwar conditions in England. Also in 1946 he served as a lecturer for the American Information Service, American Embassy, London. In 1947 and 1948 he was a lecturer in sociology at the College of Charleston, Charleston, S.C., where he lived at Prospect Hill Plantation. Under a renewal of the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1948–49, he traveled in southern France, Portugal, Gibralter, Spain, and North Africa. In 1949 he wrote, produced, and acted in The Duplin Story, an outdoor drama celebrating that North Carolina county's bicentennial. The next year he wrote and produced For Those Who Live in the Sun, another bicentennial drama, celebrating the founding of the Charleston Jewish community.

During the Coronation year, 1953, Byrd and Jack Hylton produced Stalag 17 at the Princess Theatre in London; afterward he returned to his native Eastern North Carolina to edit the Weekly Gazette at LaGrange.

He entered Duke University Medical Center in March 1955 after a leg injury, at which time leukemia was diagnosed. His funeral was held in Mount Olive at the home of his cousin, Walter T. Cherry, with whom he had spent about six months of each year since 1931. He was buried in Maplewood Cemetery in Mount Olive.

Byrd was married to Patricia Bolam, whom he had met in 1944 on a beach near Plymouth in her native England when she was ten years old. After the death of her mother in 1946, Byrd received permission to bring her to America as his ward. She attended school in South Carolina, and in 1951 they were married in Carlisle, Cumberland, England. When they returned to America, they made their home in Seven Springs.

At the time of his death, Byrd was working with Marjorie Barkentin, Jacques Wolf, and Albert Johnson on a stage adaptation of James Joyce's Ulysses. He was a member of the Players and Lambs clubs of New York.