11 Oct. 1862–1 June 1935

John Armstrong Chaloner, author, industrialist, and philanthropist, was born in New York City in the home of his maternal ancestors, the prominent Astor family. The family name, originally spelled Chaloner, was first brought to America by the Reverend Isaac Chanler, a Baptist clergyman who migrated to Charleston, S.C., from Bristol, England, in 1710. Chanler's grandson, the Reverend John White Chanler, who was ordained in the Episcopal church, married Elizabeth Winthrop, the daughter of Benjamin and Judith Stuyvesant Winthrop, descended respectively from the first colonial governors of Massachusetts and New Amsterdam. His son, John Winthrop Chanler, married in 1861 Margaret Astor Ward, the only child of Emily Astor and Samuel Ward, the original "Uncle Sam" of American folklore. After the death of her mother, Margaret Astor Ward was reared by her grandfather, William Backhouse Astor, who declined to entrust his infant granddaughter to a son-in-law whom he considered unworthy of managing an Astor and, more especially, an Astor's fortune. The Astor family approved of her marriage to Chanler, a promising young New York lawyer. Although his family lacked the huge fortune of the Astors, by birth, education, social position, and personality he was an acceptable match for an Astor heiress. Elected as a Democrat to Congress in 1862, he served for three terms until his opposition to Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall cost him the support of his party in 1868. He never again sought public office, but he did remain active in party affairs and participated in the rehabilitation of the Democratic organization following the overthrow of its corrupt leadership.

John Armstrong, known among his family as Archie or Brog, was the eldest of eleven children, ten of whom survived, born to Margaret and John Chanler. He was sent to Rugby following the death of his mother. His reports while a student there indicated that, though mentally quick, he was too undisciplined for sustained effort. After receiving his bachelor's and master's degrees at Columbia University, he attended the Collège de France and the Ecole des Sciences Politiques. He was admitted to the bar of New York in 1885. After the death of their mother in 1875 and their father in 1877, the Chanler children were reared at an Astor estate, Rokeby, by a staff appointed by the children's guardians. Upon reaching his maturity, Chaloner (who was the only member of the family to revert to the original spelling of the name) received his portion of the inheritance and entered the social world to which he was entitled by birth and fortune. He formed a law partnership with W. G. Maxwell and Henry Van Ness Philip, but his interests soon turned to the promotion of newly patented inventions, such as the self-threading needle for sewing machines. He and his brother Winthrop formed a company that purchased a tract of land near Weldon, N.C., and established the Roanoke Rapids Power Company. The cotton mill and housing for the mill workers built in 1893 by this company formed the nucleus of the town of Roanoke Rapids. The mill was designed by Stanford White, the noted architect, a close friend of the Chanlers and a minor partner in the new company. Designed more for esthetic appeal than for practical use, the mill had to be remodeled before production could begin.

During the course of his frequent trips abroad and his many business ventures, Chaloner became increasingly interested in the occult and eventually devoted much of his time and money to the study and practice of spiritualism. Convinced that he was possessed of an "X-faculty," he boasted of having an inner voice instructing him in ways in which he could exercise his power of mind over matter. He went into self-induced trances and claimed that he had changed the color of his eyes. His family had him committed in 1897 to Bloomingdale, a psychiatric hospital for people with mental illnesses in New York. During his commitment, he wrote poetry and was allowed to study the insanity laws under which he had been incarcerated. Consistently proclaiming his sanity, he escaped in November 1900 and was concealed for six months by Dr. J. Madison Taylor, a prominent physician in Philadelphia. Several leading psychologists, including William James, examined him and agreed unanimously that he was sane. Moving to Lynchburg, Va., under the assumed name of John Childe, Chaloner went to court to have his sanity legally restored. Successful in Virginia, where James testified in his behalf, he turned to the North Carolina courts, so that he could regain control of his business interests there. Though the courts of North Carolina agreed he was sane, he was still considered legally with a mental illness in New York and his fortune was controlled by his "former brothers and sisters," as he referred to his family. He fought for eighteen years to have the lunacy laws changed and his own sanity recognized.

Restricted to residence and travel only in Virginia and North Carolina, he wrote extensively, publishing his work through the Palmetto Press of Roanoke Rapids. Four Years behind the Bars of Bloomingdale appeared in 1906 and Robbery under the Law in 1914; he published collections of his poetry as well as several plays. Meanwhile, he continued his legal battles, winning several cases in which he charged libel of his name and reputation. Finally, in July 1919, he was declared sane in the state of New York and won full control of his fortune.

He used his money, estimated to be in excess of one and a half million dollars, to promote his pet projects, chief among which remained spiritualism. He lectured frequently and purchased a theater in New York City to assure himself of a platform from which he could bring messages from such dead luminaries as his great aunt, Julia Ward Howe, and Shakespeare. He turned his estate in Virginia into a rural community center, including a swimming pool, dance hall, and cinema, and at times had as many as 250 people on his payroll. He had created the Paris Art Fund in 1893, giving handsomely from his own funds to enable American artists to study in Paris, and later he established the Chaloner Prize for excellence in historical studies at Columbia University and a research fellowship at the Mackay School of Mines. He gave anonymously to numerous other institutions. He became especially interested in visual educational methods for rural areas and made two cross-county trips campaigning for such innovative techniques, leaving generous contributions to fund new projects at many stops along the way. His fortune was depleted by these varied philanthropies, and though his will included bequests to the universities of Virginia and North Carolina to endow scholarships in honor of Sir Walter Raleigh, no records at these two institutions indicate that funds were ever received from his estate.

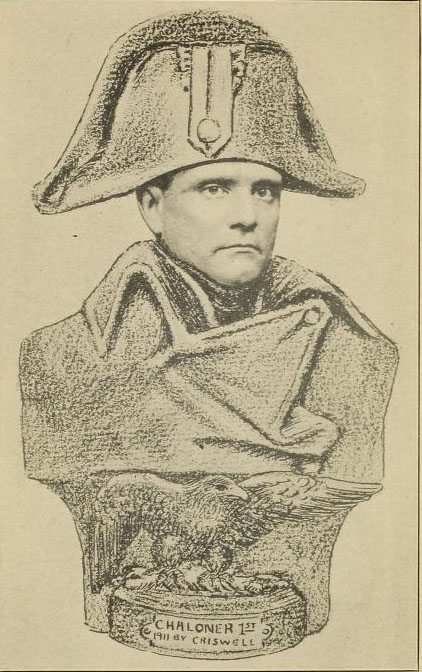

Chaloner's last years were spent in Virginia in relative quiet and poverty. He was forced to abandon a scheme to import Chinese to replace black laborers leaving the rural South. His estate was ultimately mortgaged to pay living expenses. He had consistently nurtured his physical resemblance to Napoleon, and he spent his confinement, ill with cancer, among the many statues and relics of his idol he had collected; efforts to change his hair from gray to brown proved unsuccessful. In the spring of 1935 he entered the hospital at the University of Virginia, where his estranged sisters recanted and came to nurse him until his death. His expressed wish was to be buried between the men's and women's bathhouses beside the swimming pool on his estate, but his family's sense of propriety saw fit to have him placed in the burial ground of Christ Episcopal Church near the estate.

Chaloner was married in 1885 to Amélie Rives, daughter of Colonel Alfred Landon Rives of Castle Hill near Cobham, Va. Originally arranged for October, the wedding took place in June because of the furor aroused by the first of Amélie Rives's many novels, The Quick or the Dead? which included amorous passages that scandalized many of her readers. The Chanlers were particularly outraged by the resemblance of the principal male character in the novel to their brother and urged that the betrothal be terminated. In defiance, Chaloner advanced the date of his wedding and changed his will to exclude his brothers and sisters. The marriage was an unhappy one almost from its beginning. Amélie's chronic illness and possible addiction to morphine and his own temperamental outbursts led to frequent separations. In 1895 she went to South Dakota to procure a divorce under the less restrictive laws of that state and without the public scrutiny of the eastern newspapers, which referred to her often in their social and literary columns. She soon married Prince Pierre Troubetzkoy, a Russian to whom she had been introduced by Oscar Wilde during her travels apart from Chaloner. Chaloner had no children and never remarried, but he purchased the Merry Mills, an estate near Castle Hill, and enjoyed the company of the Troubetzkoys, who became his close friends as well as his neighbors.