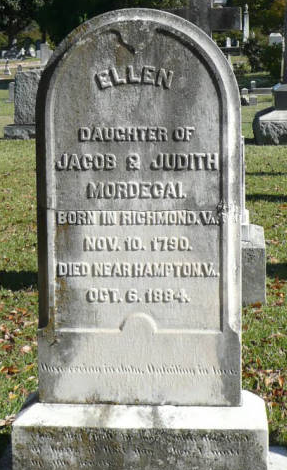

10 Nov. 1790–6 Oct. 1884

Miss Ellen Mordecai, teacher and author, was born in Richmond, Va., the fourth child and second daughter of Jacob (1762–1838) and Judith Myers Mordecai (1762–96). During her infancy the family moved to Petersburg, Va., and in 1792 to Warrenton, N.C., where her father was a merchant. After the death of her mother less than three years later, Ellen and her sister Rachel were sent to Richmond to live with their maternal grandmother, the widow of noted New York silversmith Myer Myers. There they received their early education from their aunts, Judah Myers and Richea Myers (later Mrs. Joseph Marx). In 1798 their father married his late wife's half sister, Rebecca Myers (1776–1863).

In 1809, when Ellen was nineteen, she and Rachel and their brother Solomon assisted their father in opening his successful and popular Mordecai Female Seminary in Warrenton. In addition to teaching, Ellen also had the duty of supervising—day and night—the young boarding students who lived in their home. As described in her memoirs, this regimen included keeping the "Neat List . . . inspecting the rosy digits of the little urchins." This rigorous schedule eventually impaired her health, and she spent the fall and winter of 1817–18 under the care of physicians in Richmond and Petersburg, Va., and Wilmington, N.C. During her absence, Rachel wrote of her: "she is a sort of central point to every individual of the family, and we seem at a loss when she is absent for something to which all may tend with the certainty of finding it fixed and furnished with ample resources for complying with every demand made upon it."

When, in 1818, her father closed the Warrenton school and retired to Richmond, Ellen moved there with the family and continued to instruct her young half sisters. Later she taught, in their own homes, her nieces and nephews, including the children of her brother, attorney Moses Mordecai of Raleigh. She became the proverbial welcome and useful "visiting aunt," spending weeks or months at a time in relatives' homes when needed. The possibility of her teaching at St. Mary's in Raleigh was discussed when the school opened in 1842, but the relationship did not materialize. During the 1840s and early 1850s she lived in New York City as a nanny to the children, successively, of a Dr. Francis, Rubson Maury, Denning Duer, and others.

In the late 1850s Ellen spent several winters in the Mobile, Ala., home of her favorite brother, Dr. Solomon Mordecai (1792–1869). During these visits she was instrumental in convincing him to embrace Christianity, as she herself had done earlier. He was baptized in a Methodist church in Mobile; she had become a communicant of the Episcopal church in Petersburg in 1838. Out of her experience and the spiritual conflict in deciding to abandon her family's Jewish faith, she wrote Past Days (1841) and The History of a Heart (1845). A reference in an 1848 letter indicates that one of these volumes was published abroad in a foreign language. Some of her shorter pieces were printed in the New York Review , and at least one article about Albert Nyanza appeared in the periodical, The Land We Love (1868). A third book manuscript, written between 1845 and 1847, was rejected by several New York and Philadelphia publishing houses, including Harper Brothers, John S. Taylor, and Appleton. For this memoir, entitled "Fading Scenes Recalled; or, The By Gone Days of Hastings," she used the pseudonym Esther Whitlock, the maiden name of her paternal grandmother, Mrs. Moses Mordecai (ca. 1745–1804). The work was, in her words, "founded altogether on real life" recollections of the family's years in Warrenton (Hastings), although the names of characters were largely fictitious.

Ellen's sister Rachel, from 1815 until her death in 1838, corresponded regularly with the Irish novelist Maria Edgeworth. Afterwards, Ellen continued the association, retaining copies of the letters of all three women in her voluminous personal journals and in her correspondence portfolios. Also extant are hundreds of Mordecai family letters, many of them Ellen's, intended to be read aloud and circulated among various relatives. Exceptions to that practice were the "Christian letters," so called by their writers, who instructed recipients to keep their contents private so as not to offend other family members who remained in the orthodox Jewish faith.

Ellen never married, having yielded in 1823 to family pressures to refuse the proposal of John D. Plunkett, a Roman Catholic and the son of her sister Caroline's husband by an earlier marriage. In regard to his sisters' having grown up in the only Jewish family in their town, her brother George later wrote: "There is no one thing I have felt more sensibly than the peculiarly disagreeable and unfortunate situation of our sisters in this respect. They are either obliged to lead a life of seclusion and celibacy, marry a man whom they cannot admire or esteem (for few there are of that class at least of our acquaintance who are at all estimable) or they must incur the certain and lasting displeasure of their parents by marrying out of the pale of their religion. . . . It does seem very unreasonable in them to require their daughters to do what no one can do—control their affections and direct them in a particular channel."

Ellen died at Buck Roe Farm near Hampton, Va., a seaside resort, within a month of her ninety-fifth birthday. Her remains were interred in the Mordecai family section of Oakwood Cemetery, Raleigh.