1774-1846

John Carruthers Stanly was a prominent entrepreneur and land-owning free Black in New Bern in the early 19th century. He was the son of an unnamed enslaved woman and white merchant John Wright Stanly. He gained his freedom in 1798 and built a successful barbering business, amassing a large personal fortune. He purchased the freedom of enslaved family members. And he assisted others in gaining their freedom. Stanly countersigned a loan for his white half-brother that led to his financial ruin in 1830. He died sometime in the mid-1840s. By then his circumstances were greatly reduced, and his place of burial is unknown.

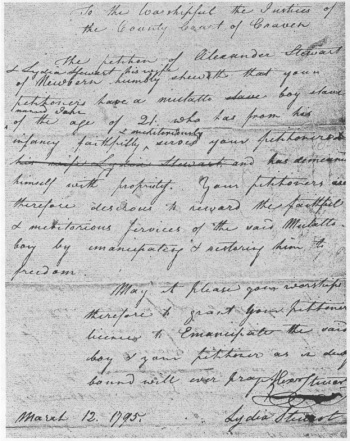

John Carruthers Stanly was born in 1774. Historical evidence suggests that he was the son of an enslaved Igbo woman and a white merchant, John Wright Stanly of New Bern. John Carruthers Stanly’s owners, Alexander and Lydia Stewart, taught him to read and write. And they apprenticed him as a barber. In 1795, the Stewarts petitioned the Craven County court to allow them to free Stanly.

After gaining his freedom, Stanly took this one step further. In 1798 he petitioned the North Carolina General Assembly to pass an act recognizing his emancipation. A few years later in 1800, Stanly began petitioning county courts to free his wife and two sons, John Stewart (Stuart) Stanly and John Florence Stanly. He legally married their mother, Kitty Green, in 1805. Green was the granddaughter of Amelia Green. She was an enslaved woman from New Hanover County who had purchased her freedom and that of several children. Stanly was instrumental in assisting other enslaved people secure their liberty. He purchased more than a dozen enslaved persons. And he posted the necessary bond for them in court to secure their freedom. He also assisted several white slaveowners, including his former owner, Lydia Stewart, in freeing their enslaved people.

Although Stanly played a key role in helping some enslaved blacks to freedom, his personal wealth was built on enslaved labor. After building up a successful barbering business, he relied on two enslaved barbers (Brister and Boston) to run the business. Stanly also owned several plantations along the Neuse River. There he cultivated cotton and produced turpentine. In the 1820s, he owned or rented the services of over one hundred enslaved blacks. Calculations of Stanly’s net worth show that he may have been the largest slave owner in Craven County as well as one of the largest in North Carolina and the South.

At the height of his personal success, Stanly was much respected in New Bern. Stephen F. Miller, a lawyer and journalist clerked in New Bern in the 1820s, recalled Stanly as “a man of dignified presence.” Stanly and his wife, Kitty Green Stanly, were members of First Presbyterian Church, where they purchased two pews. In addition to their two sons, John Stewart and John Florence, they had three other children: Catherine Stanly, Eunice Carruthers Stanly, and Alexander Stanly. Only John Stewart Stanly and Catherine Stanly remained in Craven County. John Stewart Stanly eventually migrated to Cleveland, Ohio. John’s daughter, Sara Griffith Stanley Woodward, attended Oberlin College and became an anti-slavery activist and teacher.

In 1830, Stanly countersigned a loan note for his white half-brother, John Stanly. His half-brother's dubious financial practices brought the Bank of New Bern into foreclosure. And he defaulted on the loan. This forced John Carruthers Stanly to mortgage most of his assets, including enslaved people. When creditors seized the mortgaged property for public auction, Stanly was bankrupted. He lost his barbershop, most of his urban properties, and all but one of his plantations and a handful of enslaved people. The last public record of him concerned the 1843 sheriff’s sale of his remaining piece of land. Stanly’s date of death and burial site are unknown.