Published with permission. For personal educational use and not for further distribution.

4 April 1875-11 March 1940

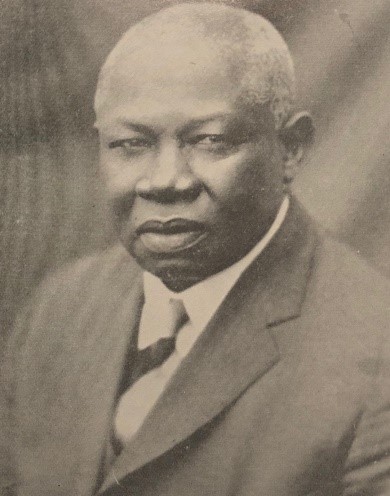

William Spencer Creecy, Sr., (April 14, 1875 to March 11, 1940) was an African-American minister and pioneer North Carolina educator in Rich Square, Northampton County.

The school at Rich Square, later named for W.S. Creecy in 1937, was founded in 1894 as the Rich Square Academy. The roots of Rich Square Academy germinated from the combination of two schools for black children: Rich Square First Baptist Church and the Willow Oak AME Church. Rich Square Academy had received limited public funds during the first decade of the twentieth-century; however, that changed when William Spencer Creecy, Sr. became the school's sixth principal; under Creecy’s leadership, the quality of the school improved, and its facilities expanded under Creecy’s leadership that ended in 1940.

Born a few miles south of Edenton, W.S. Creecy, Sr. taught at Roanoke Collegiate Institute before he assumed duties as principal in Rich Square around 1913. Creecy’s education included graduating from the Albemarle Training School, Roanoke Collegiate Institute of Elizabeth City, as well as Shaw University. Creecy maintained an active leadership role at Shaw throughout his life; he served as a member of its Board of Trustees and was President of the Shaw University Alumni Association and was the auditor for the Beulah Association. Shaw University conferred both DD and MA degrees to Creecy.

In addition to being pastor to numerous churches, Creecy gave the bulk of his time, wealth, and energy to the education of black children during the Jim Crow Era; he donated his own family’s farmland for expansion of the school; in the 1927, he created a library with a librarian; during the Great Depression, Creecy supervised the construction of an eleven-room brick school building, an eight-room brick elementary school building, and a brick teacher residence. Creecy inspired broad programs and services for his students that were largely unavailable to most black students and nurtured the creation of applied trades program for older students; with his own money, he purchased a bus to transport children who lived in distant rural areas. Children from neighboring counties such as Bertie and Hertford attended Creecy’s school at Rich Square.

Many black educational leaders during the Jim Crow Era functioned as race leaders who guided the development of the overall health and welfare of their race. For example, in 1913, Creecy was lauded as a “benefactor of his race” for impressing upon his community the importance of punctuality. In 1919, when a Farmer’s Institute was convened for the black farmers of Northampton County, a Colored Farmers’ Agricultural Society was created and W.S. Creecy was elected its president; the first resolution of the Society directed black farmers to pledge that they would have a sanitary toilet, screened windows and doors to ward off flies and mosquitos, to drink clean water, and to register infant births.

Through the 1930s and the 1940s, there was a growing ideological shift among African Americans in North Carolina who lived under Jim Crow’s oppressive social, political and economic structure. The main point of contention centered on what tactical strategies should be employed to advance their race: accommodation or active protest. In his final years of life, Creecy’s leadership came under criticism from younger, more radical, black leaders who subscribed to the more overt activism of the NAACP, rather than Booker T. Washington’s non-confrontational style of racial leadership that had preserved racial peace in order to guide white patronage to build black schools. An example of this often bitter intra-racial feud was enunciated by Louis Austin, the outspoken editor the Carolina Times published in Durham, when he nominated “Prof. W.S. Creecy of Rich Square the nation’s biggest ‘Uncle Tom’ and North Carolina’s biggest fool for 1939.” Austin’s ire was sparked when Creecy had provided a turkey dinner “during the season honoring and recognizing [white] WPA workers for their efficiency while building a Negro teacherage.”

Charles Montgomery (C.M.) Eppes, a black educational leader from Greenville and longtime adherent to the Booker T. Washington philosophy of racial leadership, rose to Creecy’s defense against these insults. In a 1940 letter to the editor of the Raleigh News & Observer, Eppes maintained that Creecy was a “safe and sane man,” not given to “inflammatory talk,” who deserved the “commendation of all of the members of the race, who are, at heart, devoted to the uplift of humanity.”

Upon W.S. Creecy’ Sr.’s death in 1940, W.S. Creecy, Jr., assumed the principalship of the school named for his father and served as its Principal from 1940 until 1976. Surviving family members of W.S. Creecy, Sr. included his wife Susie M. Creecy; two daughters, Mrs. Myrtle M. Crockett and Miss B. Frazier Creecy; and three sons, W.S. Creecy, Jr., George Hollis Creecy, and an adopted son, Luther J. Morris.