See also: Juneteenth on ANCHOR

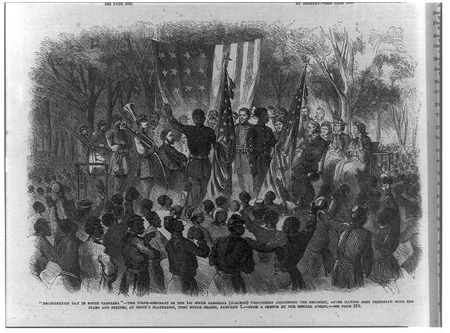

Emancipation Day in North Carolina was initiated on 1 Jan. 1865 at Union-occupied New Bern. It was conceived as a day of celebration and commemoration of President Abraham Lincoln's 1863 New Year's Emancipation Proclamation that freed all enslaved people of "persons [who] shall then be in rebellion against the United States." The day of observance included a parade through the main streets of the city with a band and an escort by the North Carolina Heavy Artillery. The procession halted at the army's parade field, where the Emancipation Proclamation was read and Lincoln was eulogized. This was followed by speeches of prominent black leaders and by meetings and dinners at local churches. The format-which became, with modifications, the model for future celebrations-was based on a similar observance held the previous year (1864) by the Federal army in Beaufort, S.C., in conjunction with local freedpeople.

Although Union forces assisted and coordinated these early celebrations to encourage defections enslaved people in the South and promote a black/poor-white alliance, the impetus of the movement was soon assumed by the newly freed black people, who had a purposeful strategy of their own: prosperity through frugality, temperance, industry, and education. By 1878, the Emancipation Day celebration had gained respectability statewide, and politicians such as Zebulon B. Vance, who continued to oppose emancipation until the end of his life, agreed to act as the orator of the day in order to compete for the votes of those gathered. Within 20 years it was generally accepted that key state and national officials and members of both races would attend the ceremonies. On 1 Jan. 1898, for instance, black former congressman H. P. Cheatham addressed an audience that included the governor, secretary of state, other North Carolina officials, numerous news reporters, and "quite a large number of ladies and gentlemen."