The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was proposed to be the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution when it was passed by Congress on March 22, 1972 and then forwarded to states for ratification. The ERA was first proposed by Alice Paul in 1923 and underwent numerous revisions and additions before its Congressional passage in 1972. The aim of the amendment is to prohibit discrimination based upon sex and to end disparate legal protections between men and women in matters such as employment, property, and divorce.

Congress originally set a deadline of seven years for the amendment to be ratified by three-fourths (38) of the states in order to become law. The ERA was ratified by 22 states in the year it was approved by congress and by 35 states before the 1979 deadline. In several states, including North Carolina, disagreement over the amendment's implications has led to many years of highly charged debate. As of December 2021, 38 states have ratified the ERA, although there is debate over the validity of several states' ratifications, due to either to the date at which the state ratified the amendment or the state legislatures rescinding of their ratification.

In 1972, both North Carolina's Republican governor James E. Holshouser Jr. and Democratic lieutenant governor James B. Hunt Jr. initially voicing their approval of the ERA. Several organizations formed in the state to support or oppose the amendment. In January 1973, 1,000 ERA supporters gathered at Duke University in Durham to launch North Carolinians United for ERA; Martha McKay of the North Carolina Women's Political Caucus was a major organizer of the event.

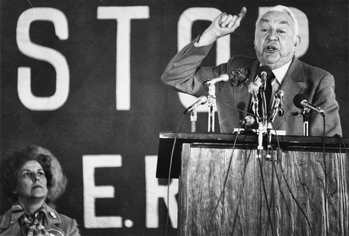

Opponents in the ERA debate were led by U.S. Democratic senator Sam J. Ervin Jr., who, after being approached by conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly of Illinois, allowed Schlafly's Stop-ERA group to use his name in its mailings. Schlafly recruited Dorothy "Dot" Malone Slade of Reidsville, a member of the John Birch Society and the National Federation of Republican Women, to lead the statewide organization, North Carolinians against ERA.

After the ERA was formally introduced into the North Carolina legislature in February 1973, many proponents were surprised by the opposition's forceful arguments that outlawing gender discrimination would have detrimental consequences. Robert E. Lee, a Wake Forest University law professor, told the Senate Constitutional Amendments Committee that the simple text of the ERA would be open to interpretation by judges, inviting what he viewed as increasing court interference in public life. Perhaps most unsettling to proponents was the organized opposition from conservative women who feared that civil society would fall into chaos if the amendment passed. While ERA supporters concentrated their efforts on lobbying the General Assembly, opponents were more successful in reaching out to North Carolina women and fueling concerns that the rights and privileges they currently enjoyed, such as maternity leave and basic courtesies, would be eliminated by the ERA. Although they may have lacked the political expertise of ERA supporters, anti-ERA activists found champions in Ervin and North Carolina Supreme Court justice Susie Marshall Sharp, a highly respected Democrat who publicly agreed with Ervin's opposition and made personal calls to legislators.

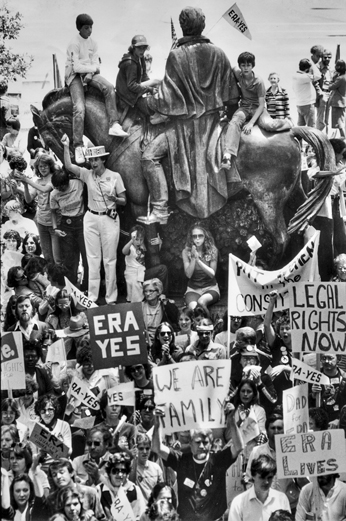

In 1973 the ERA was defeated in the State Senate by a vote of 27 to 23; it failed again in 1975. The amendment came close to passage in 1977, when Hunt became governor and it sailed through the State House by a vote of 61 to 55 on February 9, 1977. This development prompted 1,500 opponents to stage a rally at Dorton Arena in Raleigh a week before the scheduled Senate vote; the gathering, at which Schlafly and Ervin spoke, was described by one observer as "a cross between a political rally and a church revival." Opponents found success in lobbying senators, and the ERA was again defeated in the Senate by a vote of 26 to 24.

In 1978, as the expiration date for the ERA neared without ratification from the required 38 states, Congress proposed an extension of the consideration period to 1982. Ervin's successor in the U.S. Senate, ERA supporter Robert B. Morgan, maintained that an extension should in fairness also provide for a right to rescind, although his proposal was not accepted. The extension was granted by Congress, but no states ratified the amendment between the original deadline and the extended deadline. The ERA failed in the North Carolina legislature in 1979, 1981, and 1982.

In 1992, the Twenty-seventh Amendment, known as the "Madison Amendment," officially became law 203 years after it was originally passed by Congress. This led supporters of the ERA to posit that the ERA's 35 ratifications solidified prior to the original 1979 ratification deadline were still valid, and that if three more states ratified the amendment then it would become law. In March 2017, Nevada ratified the law, followed by Illinois in May 2018 and Virginia in January of 2020, bringing the total number of states that have ratified the amendment to the needed 38.

North Carolina remains one of the states that has not ratified the Equal Rights Amendment, although the issue of ratification of the ERA was brought before the NC House and Senate in 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023.

In December of 2024, Colleen Shogun, at that time the Archivist of the United States, and William J. Bosanko, Deputy Archivist, issued a statement asserting, "the Archivist of the United States cannot legally publish the Equal Rights Amendment" due to the ratification deadline and court decisions. In January of 2025, President Joe Biden issued a statement calling the ERA "the law of the land, guaranteeing all Americans equal rights and protections under the law regardless of their sex." In Biden's statement, he held that he agreed with the American Bar Association and other constitutional scholars that "the Equal Rights Amendment has cleared all necessary hurdles to be formally added to the Constitution as the 28th Amendment."

The debate over the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment continues at the national level.