From the time the first Confederate troops crossed the Potomac River under Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Ramseur, a North Carolinian, until the death of Brig. Gen. James J. Pettigrew, a fellow North Carolinian, during the retreat, North Carolinians played many crucial roles in the Civil War's Gettysburg campaign of 1863. Following the Federal rout at Chancellorsville in May, Gen. Robert E. Lee moved his army north in June to strike the enemy in Maryland and Pennsylvania. He was convinced that southern success there would accelerate the growing peace movement in the North and allow his army to gather provisions in the rich agricultural regions of the two states. The resulting Battle of Gettysburg, during 1-3 July 1863, is widely acknowledged as the greatest land battle fought in North America. At Gettysburg, the Army of Northern Virginia under Lee numbered about 75,000 men, compared to the estimated 93,000 soldiers in Maj. Gen. George C. Meade's Army of the Potomac. The battle ended with approximately 50,000 Union and Confederate soldiers killed, wounded, or missing.

!["Gen. Lee's headquarters." Created by Gettysburg, Pa. : W.H. Tipton & Co., photographers and publishers, [between 1863 and 1890]. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.](/sites/default/files/Ge._Lee_hdqtrs_gettysburg.jpg)

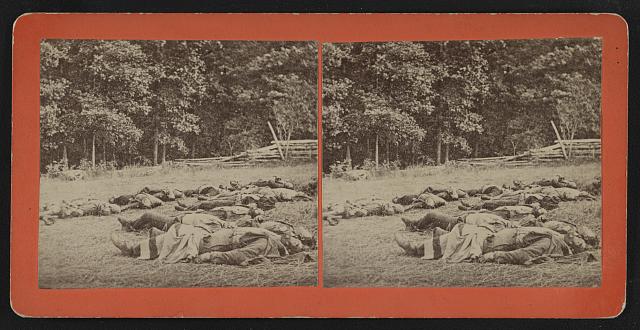

After Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's death at Chancellorsville, Lee reorganized his army into three corps, each containing approximately 20,000 men. Lt. Gens. James Longstreet commanded the First Corps, Richard S. Ewell the Second Corps, and A. P. Hill the Third Corps. Although North Carolinians could be found in all three corps, they were especially prevalent in the commands of Ewell and Hill. The Battle of Gettysburg opened early on the morning of 1 July, when Confederate soldiers from Hill's Corps encountered dismounted Union cavalry outside the town under Brig. Gen. John Buford. After an initial Confederate repulse, the battle resumed with troops from Hill's Corps attacking from the west and Ewell's men from the north. The combined force cracked the Federal line, and Union troops fled in disorder through the streets of Gettysburg. Many of the first day's casualties were North Carolinians, as 7 of the 16 Confederate brigades engaged were from the state. In McPherson's Woods, Col. Henry K. Burgwyn Jr.'s 26th North Carolina Regiment alone lost almost 600 out of 800 officers and men-including Burgwyn, who was killed. Nearby, around 800 North Carolinians out of approximately 1,500 in Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson's Brigade fell while attacking Union troops behind a stone fence. Although Lee's men pushed the Federals out of Gettysburg, at the end of the day the Union army remained in control of the high ground south of town.

On the morning of 2 July Lee's battle plan called for a strike against the Union left by Gen. Lafayette McLaws's and Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood's Divisions from Longstreet's Corps, with support from Gen. R. H. Anderson's Division of Hill's Corps. In addition, Ewell was ordered to support Longstreet's attack by assaulting the Union right on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. After an exhaustive flanking movement, Longstreet opened the attack with an artillery barrage and then an infantry assault that achieved initial success before being repulsed. Ewell responded with his artillery when he heard Longstreet's guns, and late in the afternoon, he sent troops forward to capture Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. North Carolinians in Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke's Brigade under Col. Isaac E. Avery charged up East Cemetery Hill in twilight until they were compelled to withdraw due to a lack of support. Other North Carolinians met a similar fate on Culp's Hill. North Carolina's futile efforts that day may best be reflected in the note the dying Avery scribbled at the base of East Cemetery Hill: "Tell my father I died with my face to the enemy." Despite some Confederate successes, 2 July ended with Meade's forces still occupying the high ground south of Gettysburg.

Believing that Meade had weakened his center to meet the attacks on the Federal left and right on 2 July, Lee was determined to strike again the next day. He ordered Longstreet to execute a frontal attack against the Union center on Cemetery Ridge, using Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett's Division from Longstreet's Corps and two divisions from Hill's Corps. Due to wounds suffered by Maj. Gens. Henry Heth and William Dorsey Pender, their divisions were placed under the temporary command of Brig. Gens. Pettigrew and Isaac R. Trimble, respectively. After an extensive artillery bombardment of the Union center, approximately 12,000 Confederate soldiers exited the woods on Seminary Ridge and began the long march toward Cemetery Ridge. Of the 42 southern regiments taking part in the assault, 15 were from North Carolina. The Confederate infantry was in the open, and Union artillery and small arms fire swept their ranks. Braving the devastating blasts of musketry at close range, North Carolinians made the deepest penetration into the Union, but the survivors had to fall back to the safety of Seminary Ridge. Thenceforth, the phrase "farthest to the front at Gettysburg" became part of North Carolina's proud military heritage.

The battle was a staggering defeat for the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee lost thousands of veteran officers and soldiers whom he could not replace. Indeed, the Gettysburg disaster and the fall of Vicksburg on 4 July were devastating blows to the Confederacy. One-fourth of the Confederate casualties at Gettysburg were North Carolinians, and the state lost more soldiers in the battle than any other southern state. North Carolina's final casualty came with the death of General Pettigrew during the retreat. A few days after the battle, a Richmond newspaper erroneously reported that the great charge had failed because "raw troops" from North Carolina did not support Pickett's Virginians. This story was treated as fact in many postwar accounts of the battle, and only in recent years has North Carolina received due credit for its prominent role in the Battle of Gettysburg.