11 Nov. 1923-10 Sept. 2007

Dr. Reginald Armistice Hawkins, nicknamed “Hawk,” was a lifelong civil rights activist who played a central role in integrating Charlotte schools, hospitals, and public spaces, and in 1968 became the first African American since Reconstruction to run for governor of North Carolina. Born on Armistice Day and raised in Beaufort, North Carolina, Hawkins moved to Charlotte to attend college and remained a resident of the city.

Hawkins attended Johnson C. Smith University, graduating in 1943, and was awarded a dental license from Howard University in 1948. Returning to Charlotte, Hawkins went on to earn a Bachelor (1956) and then Master of Divinity (1973) from Johnson C. Smith’s Presbyterian seminary. Hawkins, a veteran, served as a captain in the U.S. Army during World War II, and provided dental services at Fort Bragg during the Korean War, 1951-1953.

Hawkins was taught by his parents to fight injustice and began his activism as a young high school student. At JCSU, Hawkins joined the student council, quickly becoming active in boycotts and protests. In 1943, he mobilized fellow students to protest discriminatory hiring policies in the United States Postal Service. In 1948, he joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Charlotte, working closely with chapter leader Kelly Alexander and beginning a long-term working relationship with him and his brother, Fred. While at Fort Bragg’s Womack Hospital, Hawkins worked tirelessly at his practice while desegregating the base, making clear that discriminatory practices were in violation of federal law. His experience provided practical grounding in organizing the pioneering 1954 sit-in protesting segregated facilities at Charlotte’s Douglas Airport. Hawkins was refused admission to the white-only North Carolina Dental Society, and it was not until 1966 that a federal court order awarded him membership.

To directly address segregation, a tactic utilized by the NAACP was to enroll Black children at all-white schools and to seek what Hawkins termed “geographical desegregation.” In 1957, Hawkins was personally involved with the enrollment of student Dorothy Counts to Harding High School in Charlotte, an event that also changed Hawkins’ own trajectory in the movement. Counts and Hawkins were attacked by angry mob as she left the school on September 4, 1957, without any protection or intervention by police, an experience that led Hawkins to conclude diplomacy itself was not sufficient to address the challenges of racism. Shortly thereafter, he split from the Charlotte NAACP to form a new organization focused on enfranchising voters and political mobilization: the Mecklenburg Organization on Political Affairs (MOPA). Of the group, Hawkins said, “I learned from Washington, Miss Mary Church Terrell, that you could do more in one day in a ballot box that you could do ten years otherwise.” In 1961, Hawkins became the spokesman for a group of parents, the Westside Parents Council, who were concerned about the continued segregation of Charlotte’s schools. White students from Harding High had been given a new facility, while the aging building was renamed Irvin Avenue Middle School, then assigned only to Black students. Hawkins led a highly visible protest and picket of the school, right in the midst of promotion for the North Carolina World Trade Fair, embarrassing the city and forcing the school board to redress the issue.

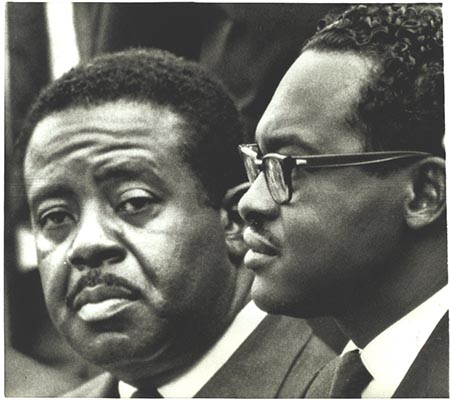

But the conflict over school segregation in Charlotte was not over. Hawkins, an acquaintance of Darius Swann, was also directly involved with the Swann family enrolling their son at an integrated school and their seeking legal recourse, and he suggested famed lawyer Julius Chambers to the family. Their case was filed January 19, 1965, culminating in the seminal busing and integration case Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971). In the midst of their activism that year, on the evening of November 22, 1965, the homes of Kelly Alexander of the NAACP, his brother, Fred Alexander, attorney Julius Chambers, and Reginald Hawkins were bombed by terrorists in a coordinated attack. No one was hurt by the blasts, but the event was part and parcel of the ongoing threats and violence dealt to Black activists in Charlotte.

Charlotte’s establishment alliances between Black leaders and white politicians were characterized by moderate and slow-paced approaches to desegregation. In contrast, Hawkins employed direct action tactics, seeking immediate change in the existing power structure. In May of 1963, Hawkins declared, “We shall not be pacified with gradualism; we shall not be satisfied with tokenism. We want freedom and we want it now." While some of his associates and colleagues sought legal recourse, Hawkins pursued highly visible protests, boycotts, and pickets, utilizing the media to publicize injustice and the effects of racism in order to empower and inspire Charlotte’s Black citizens to action.

Hawkins utilized many tactics and tools to enact change, however, including civil disobedience and legal challenges. In 1962, he succeeded in desegregating Charlotte Memorial Hospital, where he himself had been illegally prevented from practicing. He led successful pickets of numerous medical facilities in Charlotte, appealing to federal law to demonstrate how the hospitals were engaging in discrimination while receiving federal funds. In response, Memorial Hospital and other facilities enacted an open-door policy in 1963. One year later, he was jailed for registering five Black citizens who were said to have failed literacy and reading tests; such tests were later found unconstitutional and racially biased.

His 1968 gubernatorial campaign, focused on addressing inequality and poverty, energized people across the state. College students were highly involved, particularly in Chapel Hill, where Hawkins’ son, Reggie, attended UNC-Chapel Hill and was a founder of the Black Student Movement. An editorial in the student newspaper from April 23, 1968 stated, “He will tell it like it is instead spouting forth a mouthful of political rhetoric that carefully says nothing to offend anybody.” Martin Luther King, Jr. had been scheduled to support Hawkins’ campaign in North Carolina on April 4, 1968, but at the last minute, King was rerouted to Memphis, where he was later assassinated. Hawkins received 18.5 percent of the vote. Undaunted by the loss, Hawkins would again run for governor again in 1972, and while unsuccessful in securing office, the movement behind his candidacy galvanized a community of disenfranchised North Carolinians.

Hawkins, an ordained minister, also served as pastor of H.O. Graham Metropolitan United Presbyterian Church. He died at age 83 in Charlotte. He was survived by his wife, Catherine Richardson, also a Johnson C. Smith University alumnus, and his children Bibi (née Pauletta), Abdullah Salim (née Reginald Jr.), Wayne, and Lorena.

As quoted in his obituary in The Charlotte Observer, Hawkins wanted to be remembered for "having made a difference... and having the guts to have tried."