The Battle of Plymouth was a Confederate combined-arms victory of the Civil War, and occurred in April 1864. Two years earlier, in May 1862, Union forces had occupied Plymouth, near the mouth of the Roanoke River. From their bases in Plymouth, Washington, N.C., and New Bern, Union soldiers conducted frequent raids in eastern North Carolina. Meanwhile, by the spring of 1862, two Confederate ironclads under construction at Edward's Ferry on the Roanoke River and at Kinston on the Neuse River were nearing completion. The assistance of these vessels, the Albemarle and the Neuse, was essential to the success of any attempt to recapture the coastal towns. Brigadier General Robert F. Hoke, acting with Commander. James Cooke of the Albemarle, concentrated first on Plymouth.

By late afternoon on April 17 1864, three brigades of infantry–about 10,000 troops–commanded by Hoke were within five miles of Plymouth. Defending the town was a Union garrison of 2,834 men. Although badly outnumbered, Union soldiers had strongly fortified the post and repulsed the first Confederate attacks. But the next day, April 18th, saw heavy shelling, with Union vessels in the river sunk or damaged and forced to retreat to Plymouth. Meanwhile, U.S. Navy gunboats provided artillery support against the Confederates, but their success was short-lived.

During the night, the Albemarle took advantage of an abnormally high river level and safely passed over the obstructions. It slipped, undamaged, past Fort Gray to the west of Plymouth. In the predawn hours of April 19th, Cooke's ship encountered the USS Southfield and USS Miami, the most powerful Union vessels on the Roanoke. The Albemarle promptly sank the first and heavily damaged the second, forcing the Miami and two other gunboats to retreat. Late that afternoon, Hoke launched a double envelopment attack against both the east and west sides of the town. The Albemarle, having returned to Plymouth, furnished supporting fire on the east side of town.

On April 20th, Hoke renewed the attack on each flank, capturing forts from both directions. Hoke demanded the surrender of the last remaining Union stronghold: Fort Williams, near the center of Plymouth. Hoke further added that “indiscriminate slaughter was intimated” and no quarter would be given in the subsequent assault should the surrender be refused. But the Union commander, Brig. Gen. Henry Wessells, refused to surrender and gathered the remainder of his forces inside Fort Williams. Hoke ordered a “furious” artillery “bombardment” on the bastion, and the Albemarle added its two large rifled cannons to the bombardment. Heavily shelled from all sides, Wessels unconditionally surrendered his entire command on April 20th at 10 a.m. In addition to the Union garrison, Hoke captured 25 artillery pieces, at a cost of only 50 Confederates killed and wounded. His victory provided a badly needed morale boost for the Confederacy.

The 40 to 300 Black soldiers and Unionists, as well as other Black people freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, present at the Battle of Plymouth were in particular danger after Wessell’s surrender. According to a March 1864 Charlotte Daily Bulletin article, “Ransom’s brigade never [took] any negro prisoners. Our soldiers would not even bury the negros–they were buried by the negros.” Since Confederate policy differed across the levels of political administration, the fate of captured Black soldiers and Unionists was largely at the discretion of the capturing soldiers. Their treatment could range from being “restored to their” enslavers or being summarily executed. Confederate policy dictated that they were not to be treated as “prisoners of war” as white Unionists or white Union soldiers were. Massacres of Black soldiers and civilians occurred, and Confederate soldiers had massacred Black soldiers at Fort Pillow, Tennessee only eight days prior to the Battle of Plymouth. Black soldiers and emancipated people displaced by the fall of Fort Williams were treated similarly. Accounts from both Black Unionists, like that of Sergeant Samuel Johnson (Company D, Second U.S. Colored Cavalry), and Confederate occupants, like that published in the May 3, 1864 edition of the Raleigh Daily Confederate, conclude that Confederate soldiers massacred Black captives during and after the battle. Death tolls range as high as 600 and include Black Unionists, Union soldiers, emancipated laborers, and women and children.

Following the fall of Fort Williams, resistant Union forces remained around Plymouth. They remained for several hours after the surrender, but ultimately withdrew. Confederate forces moved into Plymouth and looted the town’s supplies. Food, ammunition, and other stores of materials were confiscated by the Confederate soldiers.

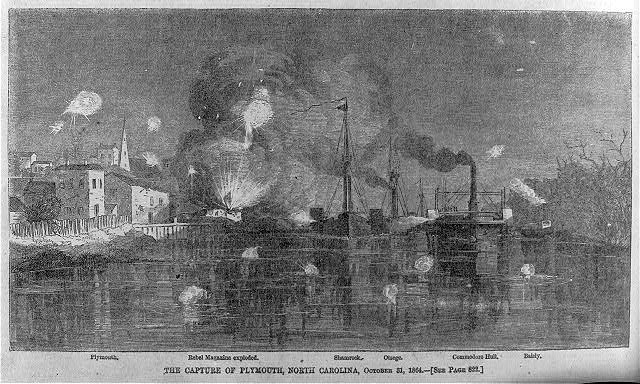

Union forces abandoned Washington, N.C., as well as Plymouth. The Confederates held the towns until the Albemarle was sunk by Union raiders in late October 1864. With the ironclad gone, the southern troops abandoned Plymouth, which remained under Union occupation for the duration of the war.