Part i: Introduction; Part ii: 18th Century - Antebellum; Part iii: The Civil War & Postwar Era; Part iv: 1880s to 1920s; Part v: The Great Depression; Part vi: 20th Century and 1970s Revival; Part vii: 21st Century and Beyond

Crazy

A major fancywork trend emerged nationally in the final decades of the nineteenth century: crazy quilting. A renewed interest in the needlecraft traditions of early settlers, which emerged during the 1876 national centennial, and a Victorian fascination with orientalism together resulted in a new, purely decorative type of quilting. Crazy quilts featured irregularly shaped bits of fabric—often expensive silks and velvets—stitched together asymmetrically. Frequently makers embellished the seams with fancy herringbone and feather stitches and embroidered or painted decorative motifs like birds, flowers, insects, pagodas, and fans onto their quilt tops. North Carolinians who could afford to do so eagerly adopted the style.

Annie Durham Armstrong of Pender County embroidered her son’s initials and the date “1894” into the center of her crazy quilt. She also stitched delicate flowers and spiderwebs onto the velvet, silk, and cotton patches. Armstrong, like most crazy quilters, did not use batting and did not stitch or tie her quilt top to the backing fabric. Such quilts provided little warmth and served no utilitarian purpose other than to show off their makers’ needlework skills and decorate a home’s interior.

The fascination with crazy quilts continued into the twentieth century; however, the emphasis on fine fabrics and embellishments declined. Some seamstresses who could not afford the silk dress fabrics and satin ribbons so prevalent during the 1880s–1890s nevertheless adapted their wool and cotton scraps to crazy-style bedcoverings. In Wilkes County, Ziliah Caroline Rash McNeill turned large leftover scraps of wool and cotton into an asymmetrically patterned quilt top with decoratively embroidered seams. She foundation-pieced her patches to lengths of repurposed cotton feed sacking for support.

Friendship Album

Another development around the turn of the century was friendship album quilting. Quilting had long served not only as an artistic outlet for women, but also a social one. The scale of the work lent itself to collaboration—especially during the quilting phase. Group projects, specifically in the form of “signature” quilts—whereby participants inked or stitched their names onto the quilt top—saw a particular growth in popularity in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Often the finished bedcoverings served as gifts for departing friends, mementos of camaraderie, or raffle prizes.

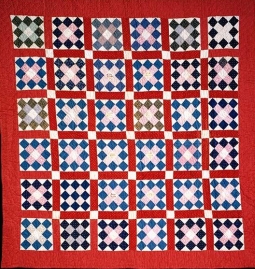

In Swansboro in 1901, a group of young girls under the leadership of their minister’s wife worked together to make a Grandmother’s Pride album quilt. They used red and yellow thread to embroider their names into the different squares on the quilt top. The finished product served as a reminder of their friendship and hard work. A few years later, in 1904, the women and girls of Locust Hill in Caswell County made a crazy-style signature quilt for beloved schoolteacher William Henry Jones, who was leaving to take a new position in Sampson County. Each contributor embroidered her name or initials, and in the corner they embroidered “Willie’s Quilt.” The piece served as a farewell gift and reminder of their affection for Jones.

Novelty

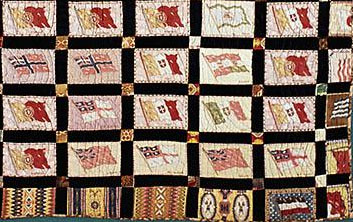

The early twentieth century also saw the development of various novelty quilting trends. The age of advertising had arrived, and some companies sought to reach female consumers’ pocketbooks through their scrap baskets. Tobacco companies gave away collectible flannel swatches with the purchase of plug tobacco to encourage customer loyalty. Piecing these inserts together and stitching them into quilts became a popular and useful way to display a collection. One North Carolina woman used “Flags of the World” and “Indian Blankets” themed inserts that the American Tobacco Company (which originated in Durham) produced circa 1915 to create a center-medallion style quilt.

Others used promotional materials in ways that were never intended by manufacturers. Espie Naomi Teague Williams and her husband, Isaac, owned a dry goods store in Maiden, Catawba County. In addition to the many wares they offered, Isaac ordered custom men’s suits from national retailers by taking customers’ measurements and helping them choose fabric from the swatch books he kept at the store. In 1927, Espie used 3” x 5” wool swatches—probably from a discontinued sample book—to create an exceptionally warm, heavy quilt.