State v. John Mann, an 1829 North Carolina Supreme Court decision, is probably the most notorious judicial opinion on the relationship between enslaver and enslaved people ever rendered by a state court. Written by Justice Thomas Ruffin, Mann stands for the proposition that enslavers were not subject to criminal indictment for a battery committed on people they enslaved.

John Mann, the defendant, had hired an enslaved woman, Lydia, from her enslaver. When Lydia fled punishment, Mann shot and wounded her. The grand jury of Chowan County indicted Mann for battery; superior court judge Joseph J. Daniel (later Ruffin's colleague on the North Carolina Supreme Court) charged the petit jurors assembled to hear the evidence that if they believed the punishment inflicted by the defendant was cruel, unwarranted by, and disproportional to Lydia's offense, the defendant was guilty under law because he was not Lydia's true enslaver. The jury returned a verdict of guilty, and Mann appealed to the state supreme court.

Ruffin took considerable pains over Mann which is evidenced by the three drafts of the opinion that survive among his personal papers. Reversing Mann's conviction, Ruffin reasoned that an enslaved person was "one doomed in his own person, and his posterity, to live without knowledge, and without the capacity to make anything his own, and to toil that another may reap the fruits." Ruffin asserted that an enslaved person would accept such a fate only if his enslaver wielded "uncontrolled authority over [the enslaved person's] body." If this authority were subjected to judicial scrutiny, it would naturally be diminished and the relationship between enslaver and enslaved person destroyed.

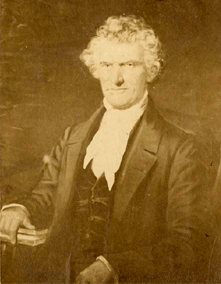

Passages from Ruffin's opinion were used by northern abolitionists as evidence of an enslaver's admission of the moral perversity of slavery. Indeed, Ruffin, one of the largest planters in Alamance and Orange Counties and the enslaver of many people, began his Mann opinion with the observation that "the struggle ... in the judge's own breast between the feelings of the man and the duties of the magistrate is a severe one, presenting a strong temptation to put aside such questions, if it be possible." One commentator gloated over Ruffin's discomfort: "The moral wrong of slavery is ... admitted, along with the most resolute determination to support it, by not allowing the rights of the master to come under judicial investigation." Despite this, the rights of the enslaver were more the focus of Ruffin's opinion, as his decision additionally stated that "the power of the master must be absolute to render the submission of the slave perfect."

By contrast, Harriet Beecher Stowe, who later wrote the celebrated antislavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), sounded a note of respect for Ruffin's candor, reporting that Mann had excited "strong interest" among English judges because of its "scorn of dissimulation" and "severe strength and grandeur . . . which approached to the heroic." To later historians, Mann, with its clearly unsettling implications, expounded a doctrine of the absolute dominion of enslaver over the enslaved that served as a reference point for southern appellate judges throughout the antebellum period.

Although some of Ruffin's language in Mann may have been excessive, the holding of the case was in fact limited; technically, the decision settled the legal consequences of a nonfatal battery of an enslaved person by an enslaver or hirer. After Mann, an enslaver could still be indicted for killing an enslaved person; ten years later this possibility was chiseled directly into North Carolina law by Ruffin, who at that point was the chief justice of the state supreme court.

A further restraint on an enslaver's, hirer's or overseer's authority left intact by Mann was the threat of civil suit for damages. The enslaver as plaintiff could seek to have civil liability imposed on a hirer or overseer for conduct similar to that of John Mann toward Lydia. Civil liability could have been only a marginal deterrent to such behavior, however, because Mann left enslavers considerable discretion to "punish" enslaved people as their own sense of humanity dictated. By removing nonfatal batteries on enslaved people from the scrutiny of judicial eyes, Mann, with its notable blend of squeamishness and severity, cast a ghastly light over North Carolina slave law and the reputation of its author that has endured for more than a century and a half.